The creeping authoritarianism of the Morrison government was often commented on throughout its term; increasingly punitive measures for protestors, the indefinite detention of a family from Biloela, and journalists’ underwear drawers being raided were just some examples used to support this claim. But last week the uncovering of a secretive centralisation of power to Morrison indicated not a creeping but a sprinting towards authoritarianism.

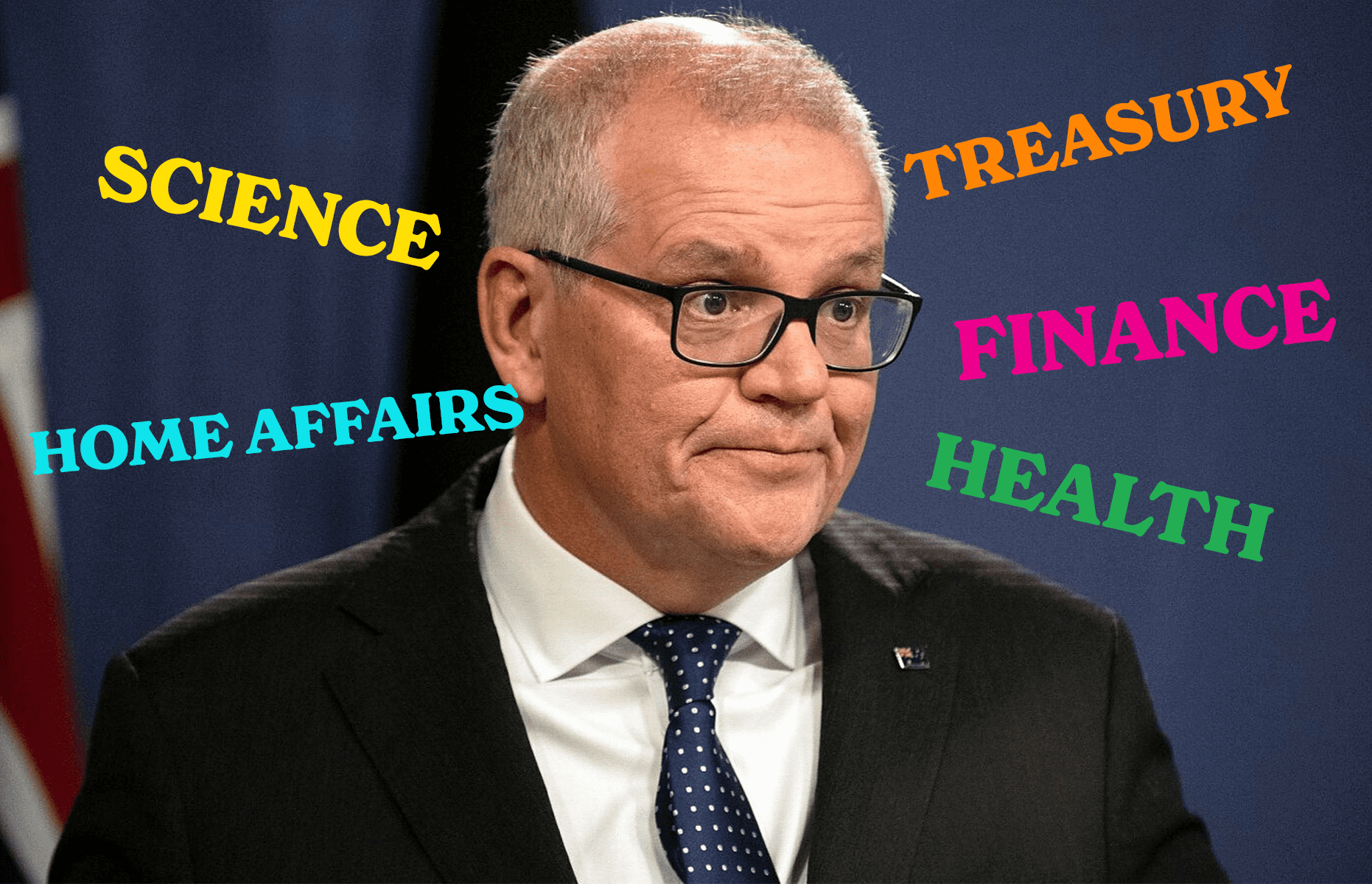

In total, five ministerial portfolios were appointed to Morrison across 2020 and 2021. The Departments of Home Affairs, Treasury, Health, Finance and Resources were all signed over to Morrison through a constitutional loophole, with four of those ministers not being aware of the arrangement. All these portfolios have unique unilateral decision-making powers, meaning that the ministers in charge of them can make decisions independent of the Prime Minister. Morrison claims he only used these powers once – to overturn the approval of an offshore gas mine in NSW where the Coalition found themselves under threat from independents campaigning on an agenda of climate action. But why should we believe him when the only thing transparent in this situation is Morrison’s blatant desire for power?

“I was steering the ship in the middle of the tempest”, was his defence when questioned on Wednesday – the use of ‘I’ further indicating his disregard for Australian parliamentary democracy, where parties, not individuals, make decisions for the nation. On Thursday, Morrison was on Facebook stating that he was having “fun joining in on all the memes” and that he was “feeling amused” with it all, seemingly not a single worry about the disrespect he exhibited towards the principles which ensure our nation’s democratic success.

Today, democracy is viewed as something seemingly natural, a state of being that the arc of history bends towards. Such an understanding of the inherent stability of liberal democracy led Francis Fukuyama to declare in 1989 that the end of history is near, where he argued that once every nation became a democracy we would live in a static world without conflict. Unfortunately, Fukuyama seems to have a serious misreading on the type of people attracted to politics. He also must never have met Scott Morrison — if he had he may have reconsidered such grand predictions.

Truthfully, and frighteningly, democracy operates on the very same logic as Santa Claus – it only works if enough people believe in it. (Admittedly more people must buy into democracy than Santa Claus, but in the same way that one eight-year-old kid can ruin the illusion of a benevolent man in red for an entire class, so too can one man ruin democracy for a nation). There is nothing natural about democracy, and to describe it like that erases the very people and institutions who work hard to ensure its ongoing functioning. At its most literal translation, democracy means rule by the people, a secret power grab by one is antithetical to this. Secrecy is a poison on democracy. Free and accessible elections, tolerance for opposing ideas, responsible governments, and politicians acting in the will of their constituents, all are crucial tenets of democracies. Above all, democracy requires the mobilisation and participation of citizens who believe that they have a choice, that they matter in determining the future of the communities they live in.

Worryingly, Australians’ trust in democracy has been waning. In 2019 only one in four Australians had confidence in their political leaders and institutions, the lowest level in forty years. In 2021, 56 per cent of Australians’ agreed that “Australian politicians are often corrupt”, and only 2 per cent of 18-29 year olds believe that politicians are working in the best interest of young Australians. These statistics fit into global trends of citizens expressing democratic disenfranchisement. This is not helped by politicians engaging in secret behaviour, nor the withholding of allegations of such misconduct by journalists to sell more books.

Morrison’s behaviour provides compelling evidence for the need for a federal ICAC to investigate such breaches. It’s time to introduce a robust anti-corruption commission, with financial independence, whistle-blower protections and strong checks and balances to ensure a balance of power. Such a commission is long overdue and is needed for Australians to have their trust in democracy restored. Labor has promised to deliver legislation establishing this by the end of the year, and we must hold them to this. To hesitate, is to allow for behaviour such as Morrison’s to go unchecked, further eroding the public’s faith in political institutions.

History tells us that democracy will not end with a bang, but a whimper. There will be no bells in the street declaring the end, no man in a suit on television notifying us that we have moved to a new form of governing. Democracy ends through a slow erosion of trust, increasing secrecy, a gradual stripping of rights from the body politic. ‘Democracy dies in darkness’, is the Washington Post’s rallying cry, but unless we act on serious breaches against democracy, it can die in light too. Morrison’s secrecy indicates how we must demand more accountability from our political leaders – our democratic future depends on it.