“I walked to a place from where I would be able to see the house, but there was something like a big cloud covering the whole city, and the cloud was growing and climbing up toward us… I could see nothing below. My grandmother started to cry, ‘Everybody is dead. This is the end of the world.’”

— Sachiko Matsuo, Nagasaki survivor

Today, the global nuclear weapons stockpile stands at 13,000 across nine countries, with five additional NATO member states hosting American missiles. Research by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute also predicts these arsenals will increase this year for the first time in decades, due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. As of 2020, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists’ Doomsday Clock stands at 100 seconds to midnight, the closest it has ever been.

In a televised national address in September, Russian President Vladimir Putin raised alarm bells by declaring: “If the territorial integrity of our country is threatened, we use all available means to protect our people — this is not a bluff.”

However, the threat of nuclear war extends beyond the immediate casualties of a nuclear conflict. In 1983, researchers at UC Berkeley started investigating the climatic impacts of nuclear war, giving birth to the controversial notion of ‘nuclear winter,’ a concept distinct from the more well-known nuclear Armageddon.

Nuclear Armageddon (or nuclear holocaust), refers to an extinction or near-extinction level event whereby nuclear war leaves infrastructure annihilated, cities leveled, hundreds of millions dead, and radioactive fallout disrupting agricultural and water systems across the globe.

Nuclear winter may well follow Armageddon, but specifically points to a case of prolonged global climatic cooling caused by vast amounts of soot emitted into the atmosphere blocking solar radiation.

Building on the work from 1983, in 2007, researchers from Rutgers University New Brunswick modelled a range of regional nuclear conflict scenarios using modern climate simulation models. They found that just 100 Hiroshima-sized bombs would produce changes to climate unprecedented in human history. This represents just 0.8 per cent of the global nuclear arsenal; furthermore, today’s warheads are anywhere from 25–80 times more powerful than those used in WWII.

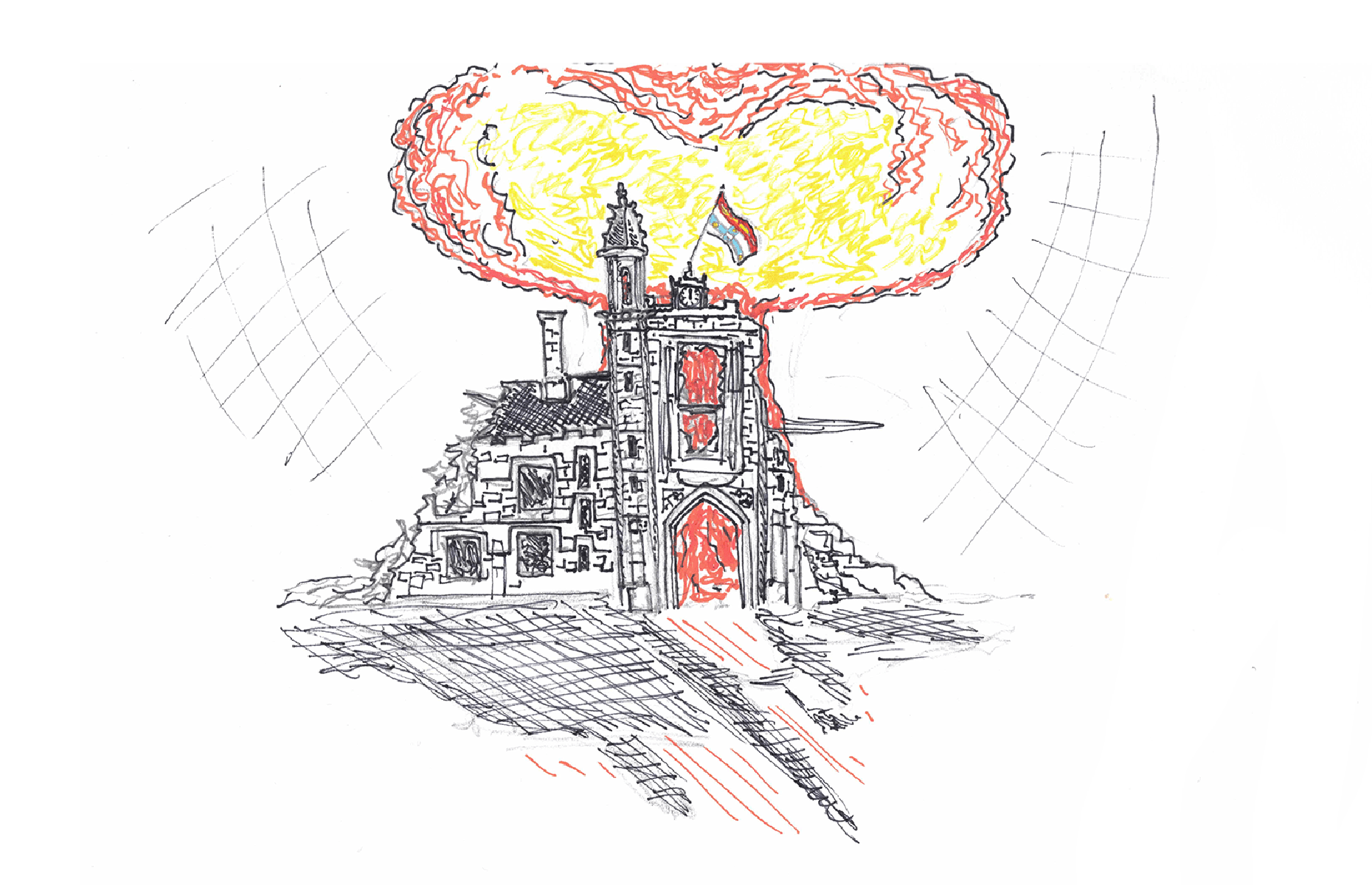

Picture this: standing in an open park in Parramatta, you see an 18 kilometre-high mushroom cloud billowing over the Sydney CBD, the cloud reaching out to Strathfield. As the vacuum created by the blast collapses, winds of 320 km/h rush to the epicentre, and fires ignite to create a firestorm that sends the remains of our city high into the atmosphere. These firestorms create their own local weather patterns, making them burn hotter and longer. Many across the world stare as their cities are also set ablaze.

One only needs to remember the 2019–20 Black Summer bushfires to imagine what the skies would look like. Over the course of two months, these bushfires launched one million tonnes of soot into the atmosphere. In this regional nuclear war scenario, such an experience would be widespread, with over five million tonnes emitted over the course of a day.

In the wake of the initial fallout, dark storm clouds would blanket our cities with black rain. Eventually, the skies would clear; unfortunately, the emitted aerosols would not. Superheated firestorms distribute significant volumes of carbon aerosols high into the atmosphere, where they would remain for up to ten years. We may not see them, but would endure their presence in other ways.

Within two years, surface air temperatures across the Australian east coast would drop between one and three degrees Celsius; meanwhile, South Australia would drop between two and four. Australian farmers would lose up to 20 days in their annual growing season. With similar collapses in output across the globe, such a scenario would cause the unprecedented diminishment of our food systems, even if a full-scale nuclear winter did not come to pass.

In the face of global warming, one might welcome a decrease in global temperatures. However, the outcome of such a scenario would cause a catastrophic collapse in agricultural output; in the first year of nuclear winter alone, billions would die from starvation.

A full-scale nuclear winter scenario could be precipitated by an all-out war between Russia and the United States today, according to updated modelling from 2019. If the countries’ entire nuclear arsenals were deployed, over 150 million tonnes of soot would be sent into the atmosphere, causing surface air temperatures to drop by up to nine degrees Celsius.

Our civilisations and their social systems exist in delicate balance with the Earth’s natural systems. Like climate change, nuclear winter poses an existential threat to human civilisation as we know it. Both serve to remind us that our survival is intimately tied to climatological processes that can be violently disrupted — in just a moment, with nuclear war, or in slow motion, with continued fossil fuel use. In both instances, our political, economic, and social systems must adapt to prevent that disruption.