To the Australian public and Prime Minister

Regarding the trial and extradition of Julian Assange,

Signed by the young journalists of Australia.

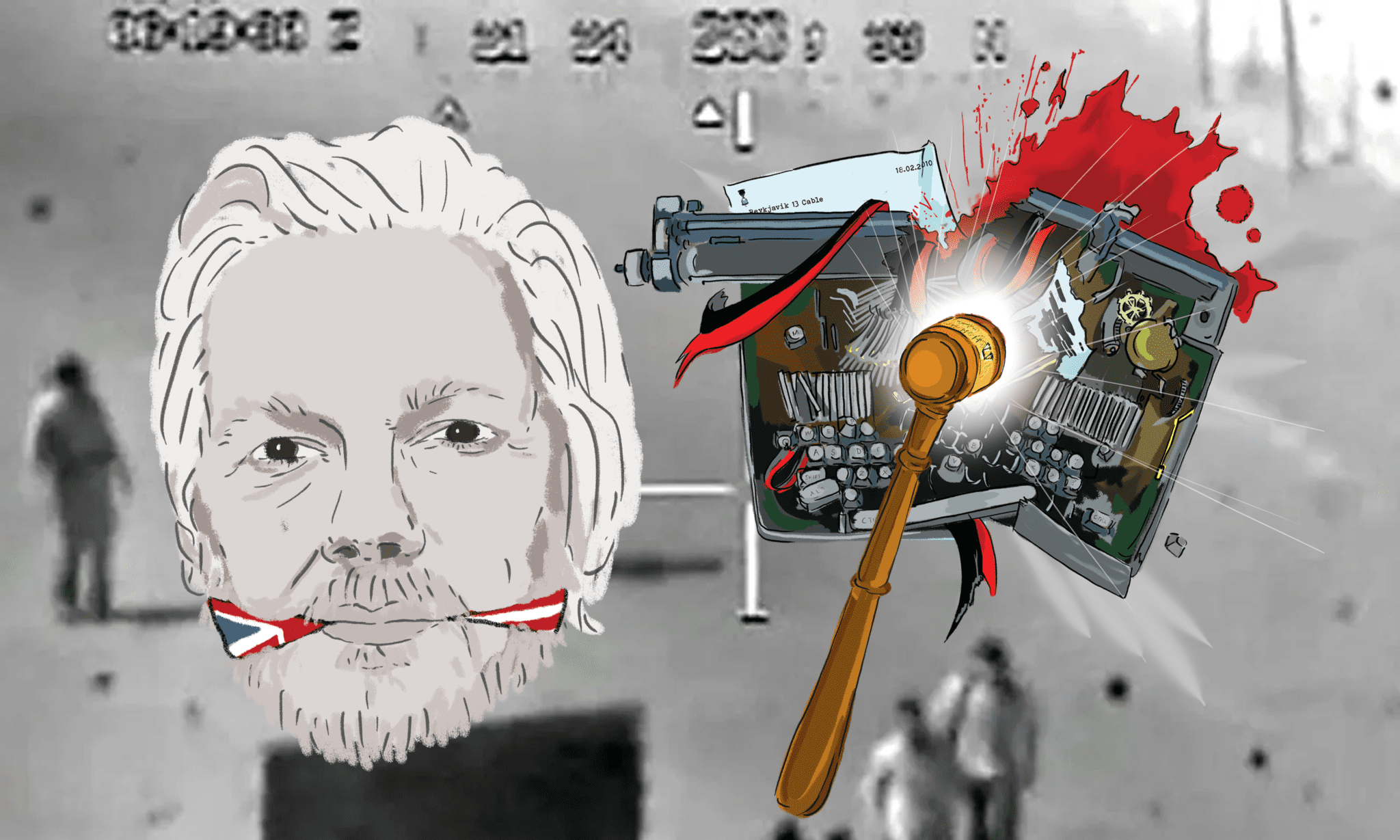

The Australian journalist Julian Assange is being held in the United Kingdom’s high-security Belmarsh Prison. His health is rapidly deteriorating. Assange has been in detention since 2019, having spent the seven years prior in London’s Ecuadorian Embassy where he sought political asylum. He awaits extradition to the United States on seventeen charges under the Espionage Act 1917 (USA) relating to his position as Editor-in-chief at WikiLeaks.

In this letter, we will make the case that the Australian Government is obliged to intervene in the extradition process to have the charges against Assange dropped and to have him brought safely home. We ask that you read this letter in full and with an open mind. We hope it motivates you, in a time marked by waning journalistic standards and commitment to truth, to join those voicing the need for intervention.

It is an irrefutable and troubling fact that during the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars the United States and its allies, including Australia, were responsible for the negligent and at times intentional killing of thousands of civilians, and that during and after those conflicts it was the policy of Western intelligence agencies, chiefly the Anglophone intelligence network, to suppress knowledge of these murders.

It is irrefutable, for instance, that on 15 March 2006 US forces in Ishaqi, Iraq committed the extrajudicial execution of a household of eleven civilians, five of whom were children, by restraining them with handcuffs and executing each with a bullet to the head. It is irrefutable, also, that on 4 March 2007 a group of US Marines in Shinwar, Afghanistan indiscriminately shot and killed nineteen unarmed civilians, wounding a further fifty, while retreating from the aftermath of a suicide attack. It is irrefutable that on 12 July 2007 a US Apache helicopter flying a sortie over Baghdad, Iraq killed two Reuters journalists and sixteen other civilians, a crew-member laughing “Oh yeah, look at those dead bastards” as they did so.

These claims can be described as ‘irrefutable’ because a brave and uncompromising cohort of whistleblowers and journalists were willing to secure and disseminate what are known as the ‘Iraq War logs’, ‘Afghan War Diary’, and ‘Cablegate’ files: a series of documents that were held by US intelligence agencies and kept from public disclosure. The examples above are only a selection of the revelations that characterise these leaks — they were published, in part, over the course of 2010 by The New York Times, The Guardian, Al Jazeera, Der Spiegel, and WikiLeaks. These publications were provided the material by WikiLeaks, who in turn received it chiefly from the whistleblower Chelsea Manning, a former intelligence officer of the United States Army. Most of the contents of these three leaks, some tens of thousands of documents, remain unpublished owing to the way the United States Government responded to initial publications.

Reckoning with these crimes as Australians is confronting: innocent people, a startling number of whom were children, were murdered. While the civilian death tolls of both wars — ~180,000 in Iraq and ~45,000 in Afghanistan — are the egregious and senseless result of the interventions in their entirety, it is abhorrent that evidence exists of specific instances of murder, committed by identifiable combatants, and that this evidence spurred no criminal investigations or charges.

These murders occurred in wars prefaced on ending human rights abuses and bringing about democracy; the unfortunate irony in this fact seems to have been lost. Not only was the decision of intelligence agencies to censor access to this information dishonest, it was utterly undemocratic. The Australian public had then, and maintains now, the right to know when crimes are committed on our behalf and in our names. So too does the American public, and other nations represented in the coalition forces, and the world at large. Freedom of information is a prerequisite to functioning democracy. A state that is no longer accountable to its public but instead to an intelligence network should no longer describe itself as democratic.

The justification given by intelligence agencies for the suppression of this material is simple: public access to it amounted to a national security risk, be that the security of the United States or its allies. The logic of such an argument is left wanting — the risk to a state’s security in having its crimes exposed is unclear. Even if we accept this assertion, why, in a country that has proven itself capable of prosecuting while simultaneously limiting access to sensitive information, were no charges ever brought against those responsible for the crimes these documents evidence? The sanctity of ‘national security’, a term with indefinite scope, proves itself a useful guise for omitting responsibility. The harm suffered by the United States and its allies was, plainly, to their legitimacy as democratic global actors.

How, then, can we, the Australian public, remain idle when an Australian faces the prospect of life in the torturous and dehumanising confines of an American high-security prison — the same carceral system that drove Chelsea Manning to attempt to end her life in similar circumstances?

While those responsible for the murders documented in these leaks have never been held to account, Assange, on the other hand, faces 170 years in prison across seventeen charges. Not only is the principled case for Assange’s release clear, but the legal foundations these seventeen charges rest on are dubious.

To date, there exists no precedent in which the Espionage Act 1917 (USA) has been used to convict a person for disclosing secure information that was not an employee of the United States Government. While federal employment is not a requirement under the Act, where similar charges have existed no conviction has ever been reached. It was the stance of the Obama administration that pressing charges against Assange under the Act would set a dangerous precedent that would infringe the rights of journalists — the charges were later unsealed by the Department of Justice under Donald Trump as the statutes of limitations neared their end.

The scope of who has been charged under the Act is also odd: Chelsea Manning, then a US Federal Government employee, was court-martialed and convicted under the Act in 2011 for her involvement but had her sentence commuted by the Obama administration. What’s more, publications like The New York Times, The Guardian, Al Jazeera, and Der Spiegel are equally incriminated for acquiring and publishing the leaked material. By the standard of involvement set by the charges levelled at Assange, half a dozen parties should share culpability but he alone faces punishment.

In the past, whistleblowers and journalists were assured immunity. The publication of documents pertaining to the public interest held in secrecy by government agencies is a historical function of investigative journalism — there is nothing new about the kind of work Assange performed. He held a mirror up to agencies behaving with impunity and now faces the wrath of an embarrassed and empowered security apparatus.

If the information Assange disseminated was fundamentally within the public interest; if it was the stance of the Obama administration that convicting Assange would set a dangerous legal precedent allowing for the targeted persecution of investigative journalists; if the standard of culpability held by Assange is shared by the editors-in-chief of a number of news outlets that were never charged; if Chelsea Manning had her sentence commuted for her role whistleblowing; if the Whitehouse is now occupied by a Democratic President who served as Vice-President in that very Obama administration; if that President maintains the right to intervene and have Assange’s charges dropped; and if that President shares amicable relations with our Prime Minister, why hasn’t the PM picked up the phone?

It is feasible that the Australian Government could secure Assange’s release and return to his home country. It is necessary. To say “it’s none of our business” is to ignore that Australian soldiers fought in those wars, that Assange is an Australian, and that defending the rights of journalists, Australian or not, should always be the business of supporters of democracy.

Please Prime Minister Albanese, make the call. Bring Julian home.

Will Solomon

Signed, the editor(s) of

Honi Soit, the University of Sydney;

Carmeli Argana

Christian Holman

Amelia Koen

Sam Randle

Fabian Robertson

Thomas Sargeant

Ellie Stephenson

Khanh Tran

Zara Zadro

Farrago, the University of Melbourne;

Nishtha Banavalikar

Jasmine Pierce

Charlotte Waters

Semper Floreat, the University of Queensland

Jack Mackenzie

Isabella Tower

Alexandra Tolley

Cloey Capewell

Eric Yun

Hamish Barnett

Grace Cameron

Rabelais, La Trobe University

Lewis Kimpton Drake

Callum Burkitt

Dylan Vigilante