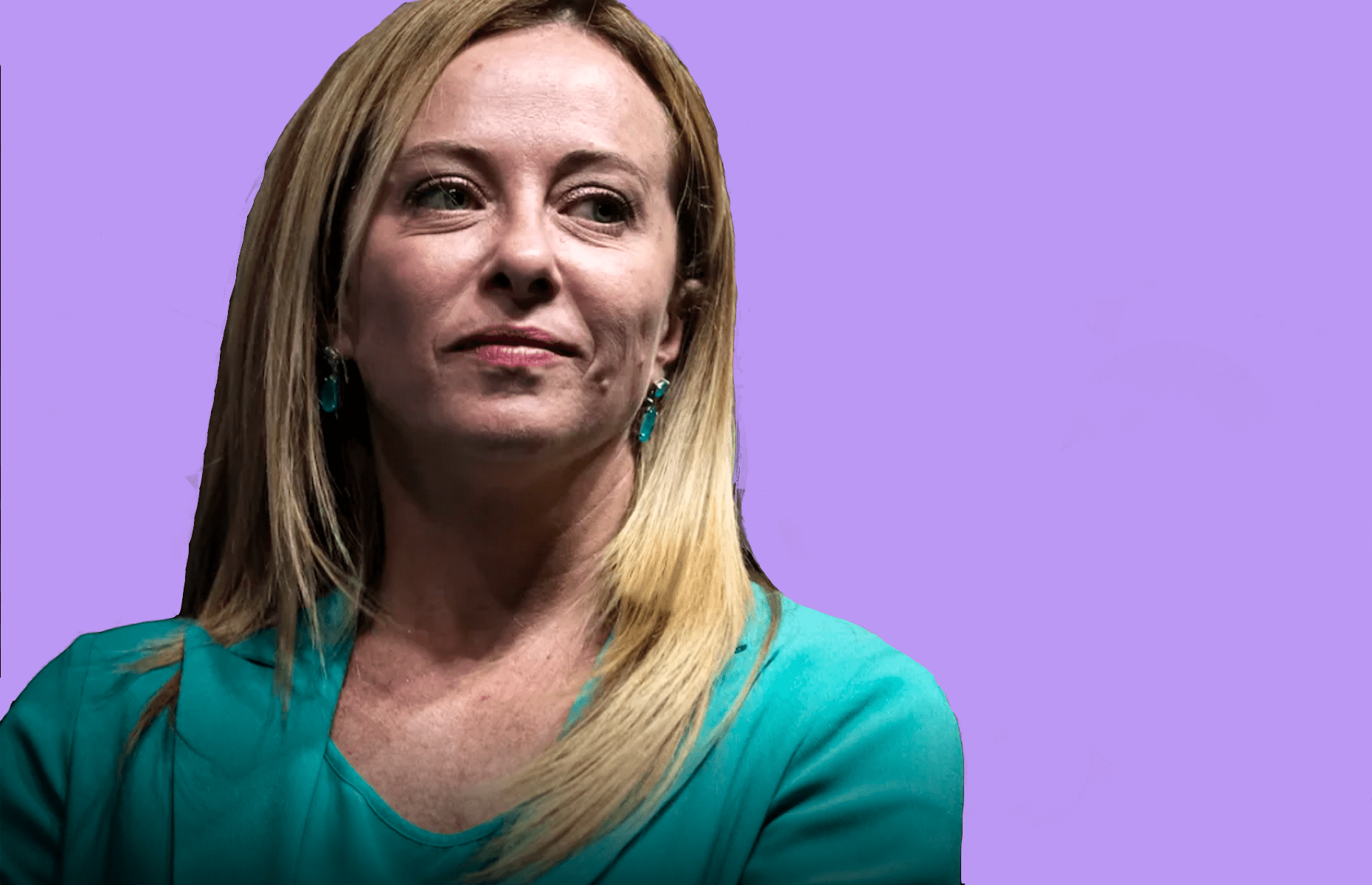

Following a landslide election victory, far right leader Giorgia Meloni is likely to become Italy’s first female Prime Minister. With around 44% of the vote, her and her far right coalition are set to dominate both the Senate and chamber of deputies (lower house).

Four years ago, Meloni’s rise to power was quite unfathomable, with her party Fratelli d’Italia (Brothers of Italy), receiving only 4 per cent of the vote in the 2018 elections. Nonetheless, her party was one of the only political entities to abstain from the national unity government that formed in response to the global pandemic. As virtually the only opposition, her party saw a sharp increase in support. Consequently, when Mario Draghi’s coalition collapsed in July, Meloni was primed to strike and subsequently managed to transform her largely fringe group into the dominant conservative force of contemporary Italian politics.

As a founding member of the EU, and Europe’s third largest economy, Italy’s new government has significantly altered Europe’s geopolitical reality. Although Meloni assured voters that she is pro-EU and pro-NATO, she nonetheless remains Eurosceptic, and wishes for “less centralism, more subsidiarity, less bureaucracy, and more politics”. Furthermore, Meloni’s coalition partner and former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi, leader of Forza Italia, is openly Pro-Russia, with close ties to Putin.

Additionally, Meloni’s election is demonstrative of the power and sway held by nationalist populism, a phenomenon that has only increased in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. Her success sends a sharp message to Europe that voters are disillusioned with the systems that should support them, a message furthered by Italy’s low voter turnout of 64 per cent this year– the lowest recorded in the country’s history.

Furthermore, her election has set off global alarm bells for fascism, with CNN describing her as “Italy’s most far right leader since Mussolini.” Despite having roots in the neo-fascist Italian Social Movement, which was founded in the aftermath of World War 2 by the remnants of Mussolini’s supporters, Meloni is nonetheless adamant that fascism has been consigned to history. Despite this, her party continues to utilise fascist iconography and slogans, such as Mussolini’s tricoloured flame as the party’s logo, and neofascist rhetoric such as “Dio, patria e famiglia” – God, country and family.

On a smaller scale, Meloni’s election has young people in Italy worried. Although Meloni has promised to govern “for all Italians”, she nonetheless ran on a platform that targets and further marginalises minority groups. Her central election message was a call to return to “traditional” values, whereby the white nuclear family is the building block of Italian society. She is vocally against LGBTQ+ families, and wants to continue the ban on same sex marriage and same sex or single sex adoption. She is also anti-immigrant, and calls for a naval blockade to prevent migrant boats leaving North Africa from entering Italy, and for Italian parents to produce more children to solve labour shortages, rather than allowing a reliance on foreigners.

Italian student Nadège Bisoffi told Honi that during this election, more than ever, “young people felt the need to go and vote… The threat of the far right scared young people into the booths”.

Although this was the first election in which some young people enjoyed full voting rights, with the minimum voting age for the upper house lowered from 25 to 18, their voices pale in comparison to the ageing population’s total eligible voters, of whom there are 51.4 million.

Meloni’s return to the nuclear family also creates a concerningly oppressive environment for women, reinforcing their role in the domestic sphere as mothers and caretakers. For this reason, it is ironic that Meloni herself is the woman likely to shatter the political glass ceiling by becoming Italy’s first female Prime Minister. But even in the political sphere, she has been careful to craft her image so as not to challenge mainstream ideas about what women can and cannot do. With her stern manner, she embodies the archetypal Italian “mamma”, ready to govern the country as one raises a child.

Consequently, her image both enforces and challenges gender roles, a paradox that has ultimately been one of her greatest political assets – she appeals to both men and women alike, without ever ultimately breaking the moulds of Italian society.

It is these oppressive gendered, sexual and racial policies that make young people concerned. USyd engineering student Giulia Emmanuelli told Honi that the thought of Meloni becoming Prime Minister makes her “feel sick”.

Other students, such as those at Milanese school Liceo Manzoni, protested by occupying the school building not even 12 hours after the victory of the right. They stated that the purpose of the occupation was “to speak about the situation that our lives are in. We are preparing to enter a political phase that is dangerous and repressive”.

Italy can expect to see more actions like these as actions of the right-wing government unfold. Time will tell if they have the ability to turn the tide of the neo-fascist wave.