International House sits on City Road across from Victoria Park, between the Wilkinson Building and the Seymour Centre. Since opening seven odd decades ago, it has been home to just over 6,000 students and fostered a culture that is seemingly unreplicated in any other student accommodation.

At the end of 1966, the first residents moved into International House — a year before Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were counted in the Australian population and allowed the right to vote, and seven years before the White Australia Policy would be officially denounced by the Whitlam government.

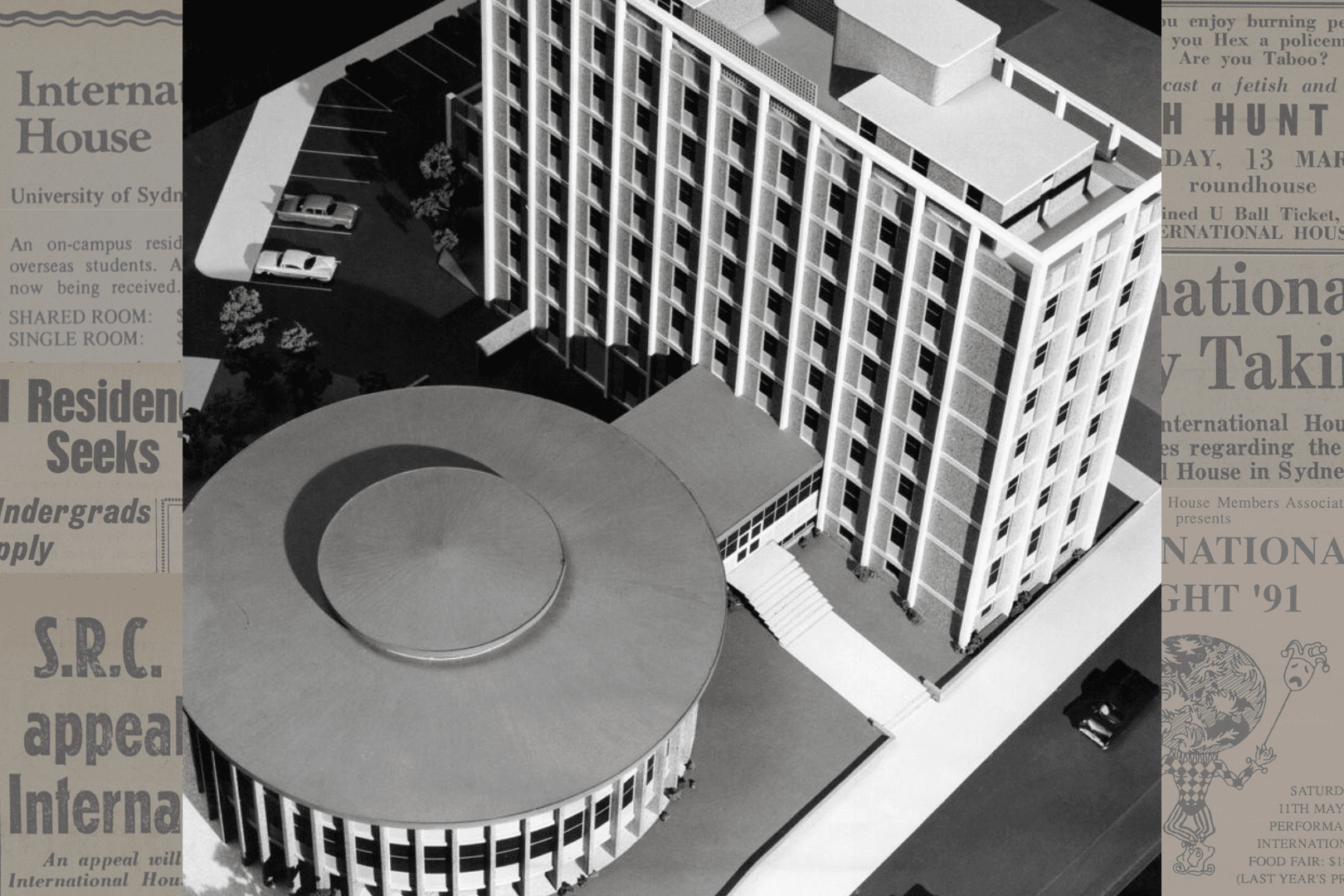

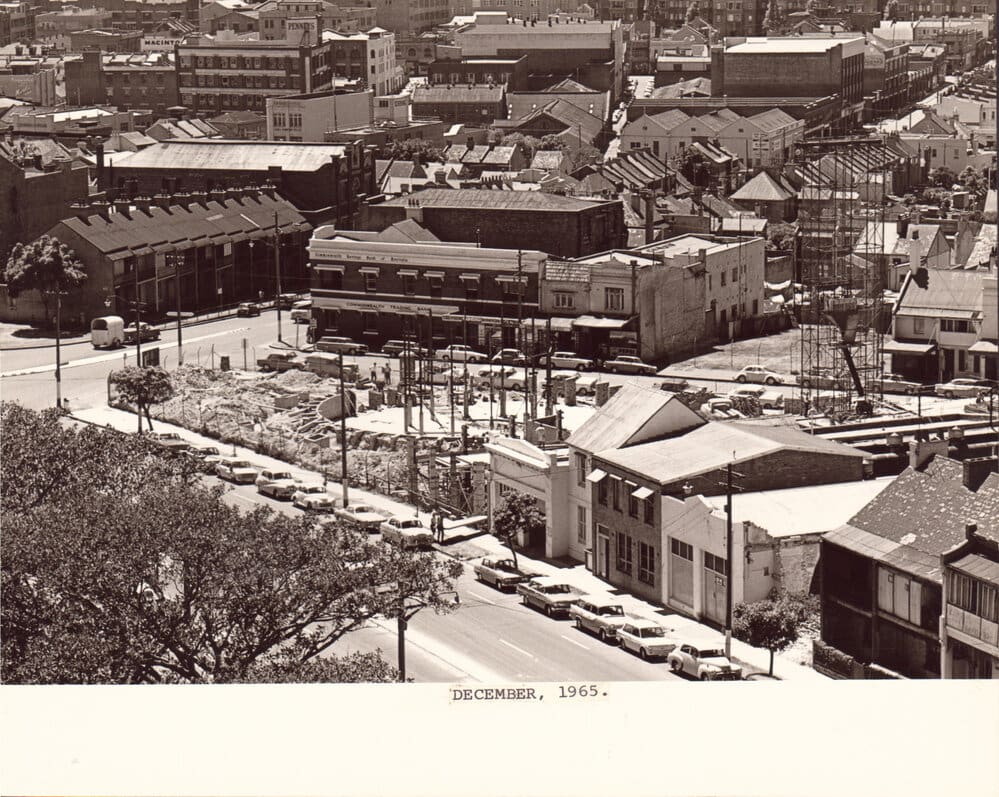

The land that International House would sit on, at the corner of Cleveland Street and City Road, was acquired by the University between 1960 and 1963, and saw the demolition of at least 16 homes and a pub, the Junction Hotel. Construction began in 1965, under the design of renowned Australian architect Walter Bunning. Now, it’s one of just a handful of publicly visible buildings by the architect — the other of note being the National Library in Canberra. It exemplifies a cultural movement forgotten by the University architects and capital works planners of today, designed with an emphasis on a timeless aesthetic appeal, ongoing practicality, and communal interaction.

The International House movement was a global one, starting with a house at Columbia University in the 1920s. At the core of the concept is global citizenship — the belief that it would benefit all students, foreign and domestic, to live together, eat together, and study together. At the time, the idea that university accommodation should be built with an abstract benefit — a cultural one, rather than an economic one — was truly radical, and something we should admire.

Like many overseas movements, the International House wave arrived in Sydney a little later than elsewhere, in the mid-50s. A report was delivered by the Secretary of the Overseas Student Bureau, Margaret Briggs, expressing the need for such accommodation.

Not long after, the University of Sydney SRC took on the campaign, pushing for the university community to open its mind and understand the importance of challenging its social perceptions of people from other countries. One of the main talking points was that the House wouldn’t just benefit overseas students, it would also benefit domestic students by giving them the opportunity to learn from people with entirely different experiences and world views, something hard to come by when television was still black and white, and overseas telephone calls put you back two weeks’ pay.

Dr Harold Maze (whose name you may recognise from the Maze Building, or Maze Crescent along Cadigal Green) was appointed to the planning committee by the University in 1959. Serving as Deputy Principal at the time, Dr Maze committed himself entirely to seeing through the plans for the House. The eventual involvement of Rotary — a humanitarian service organisation — brought the House to life. Their fundraising efforts pooled enough money to kickstart its creation, an area the University failed to provide in, and became intimately involved in the management and administration of the project.

Crucially, the House’s governance was not to be entirely overseen by the University. While its executive body is a Senate-approved council which does consist of University members, it also includes representatives from the Rotary, House residents, and alumni.

The document which regulates its visions, goals and governance is the Trust Deed, written in 1962. It makes clear the council’s hope of “promoting goodwill and understanding among students” and that “such Houses should be completely self-contained having their own dining rooms.” It also states that the “House shall be managed and controlled by an independent Board of Management … in which shall rest the ultimate responsibility … and shall be managed separately and apart from the university.”

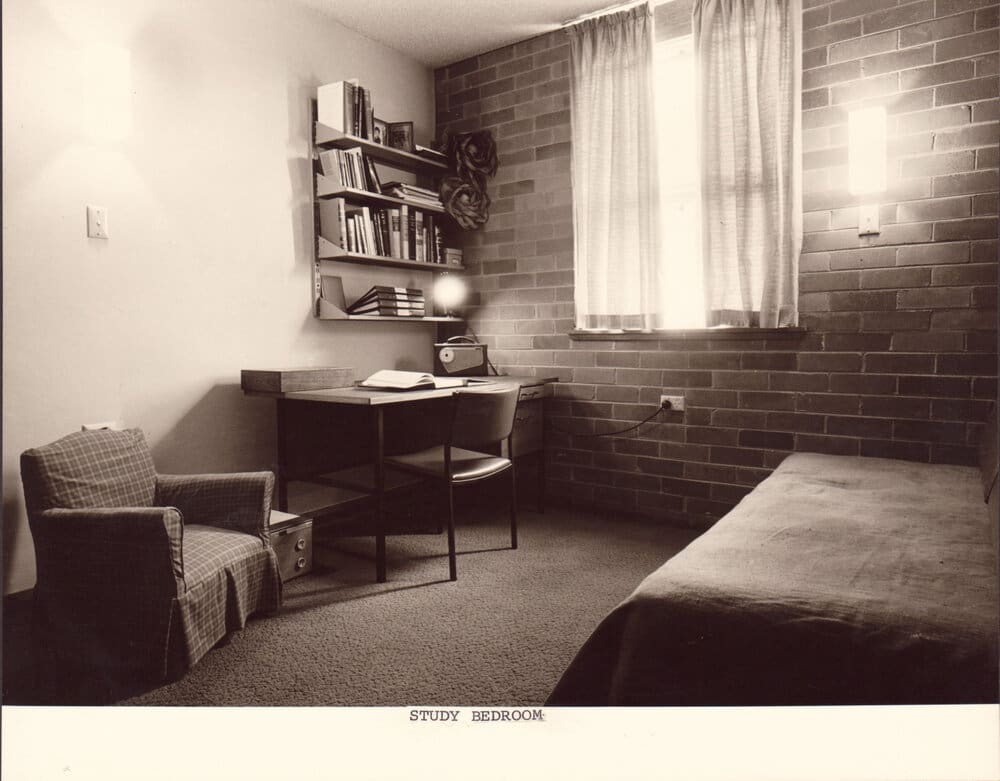

When a Project Planning Committee was established in 1964, they stated “the House will have two main purposes. On the one hand it should provide for strangers in a strange land, facilities for living and study as individuals under reasonably comfortable conditions. On the other, it should provide opportunities for easy contact between individuals and groups of overseas students with Australian students. In regards to the latter objective, particular significance is to be attached to the provision both for eating facilities, communal and incidental and places for social intercourse, recreation and conversation.”

The first stage of International House buildings, which includes the Rotunda and the 8-storey building, has been listed by the National Trust of Australia. The Trust’s heritage classification report of International House notes its architectural significance as a “representative Sydney example of an international genre of buildings”, referring to its place in the 1960s modernist movement. But what the report places greater emphasis on is the building’s social significance, and how it’s explicitly linked to ideas employed in modernist architecture.

“The International House at the University of Sydney, dating from 1967, is historically significant for being amongst the first university colleges to offer secular accommodation for students in NSW,” the Trust points out.

“International House was deliberately designed to provide more independent, inexpensive and culturally flexible accommodation for a multicultural array of residents of both sexes and all ages, both domestic and international.

“These consciously modern, cosmopolitan social expectations of encouraging interaction and integration between cultures are expressed in the modernist architectural style of the building complex and by its location on the city side of the campus, bounded by busy roads and public transport rather than being located in the more suburban, park-like college precinct.”

These factors comprise a unique and successful place of university accommodation, which the University of Sydney seems to have forgotten.

Dr Harry Bergsteiner is an architect, town planner and management scientist who works in adaptive reuse, and spent 12 years in Europe working on repurposing plans for centuries old structures like castles and palaces. He was also the first person to apply for residence at International House, way back in 1966, before it had even finished being built. He’s a Fellow of the House, served on the Alumni Association, and sat on the Council for 11 years (the last two of which he needed special permission from the Senate for, because he’d exceeded the statutory time limit on terms).

Harry spoke to Honi about the importance of shared spaces to the International House experience.

“I liked having other people from my floor, which included people who were Indonesian, Indian, Asian, various nationalities — I’d have them in my room for coffee. And I used to also invite the women, because my floor was all men.

“One of the women, now a barrister in Australia, London and New York, told me one day: ‘early on, when I stayed in International House, I was so grateful to you for inviting me to coffee’,” Harry said, explaining the conversation.

“And I said, ‘What? What’s the big deal about being invited to coffee?’ ‘Well, you know, I came from a little town, south of Wollongong, with a very small circle of people I knew. And then all of a sudden, I’m at Sydney University with all of these people from different countries.’”

The concept of International House was, as a baseline, ahead of its time. As a natural consequence, its residents adopted a similar forward-thinking mindset in all aspects of their thinking and behaviour. International House was one of the only residential facilities on campus that didn’t place men and women in separate buildings. Male residents didn’t think twice about having women in their dorm. At St Paul’s College, they are only just adjusting to the idea today, decades later.

In 2018, residents of International House were notified that they would be required to relocate to the newly-opened Regiment Building by December 2020. One of the move’s immediate alarm bells was the evident loss of communal spaces, a hallmark of International House. Most apparent throughout this article’s research was how important these spaces were: the relationships between students, formed slowly and naturally through sharing common spaces, was what made the House special.

At the centre of this was the dining hall, where residents were served three hot meals a day. Notably, tables were round and there was no ‘high table’.

“This is how you get the Australian students and the overseas students to actually interact,” Harry said. “The whole idea of International House was half Aussies, half overseas. And the overseas students, even with a common dining room, had a real struggle with the interaction. A lot of their cultures tend to be much more reserved, you know, they’re not as upfront as Australians.”

Research from the University of Melbourne in 2007 found that integration with local students helps international students lead a happier and healthier life in Australia, feeling less homesick and culture shock. Additional research by University of Technology Sydney in 2020 also found that 47 per cent of international students agreed or strongly agreed that making close friends in Australia was difficult, and 35 per cent said they felt lonely while here.

Harry emphasised that continuous shared spaces can bridge social barriers between international and domestic students.

“The idea was, if students have to go into the common dining room, to have breakfast, to have lunch or to have dinner, and mostly they do, because they haven’t got the money to go to restaurants all the time. Eventually, not by fate, but by circumstance, they’ll get to know each other. This is precisely what happened.”

Meanwhile, The Regiment doesn’t have a shared dining area — while it may have an open eating area, the individual cooking areas and separated tables don’t invite social dining.

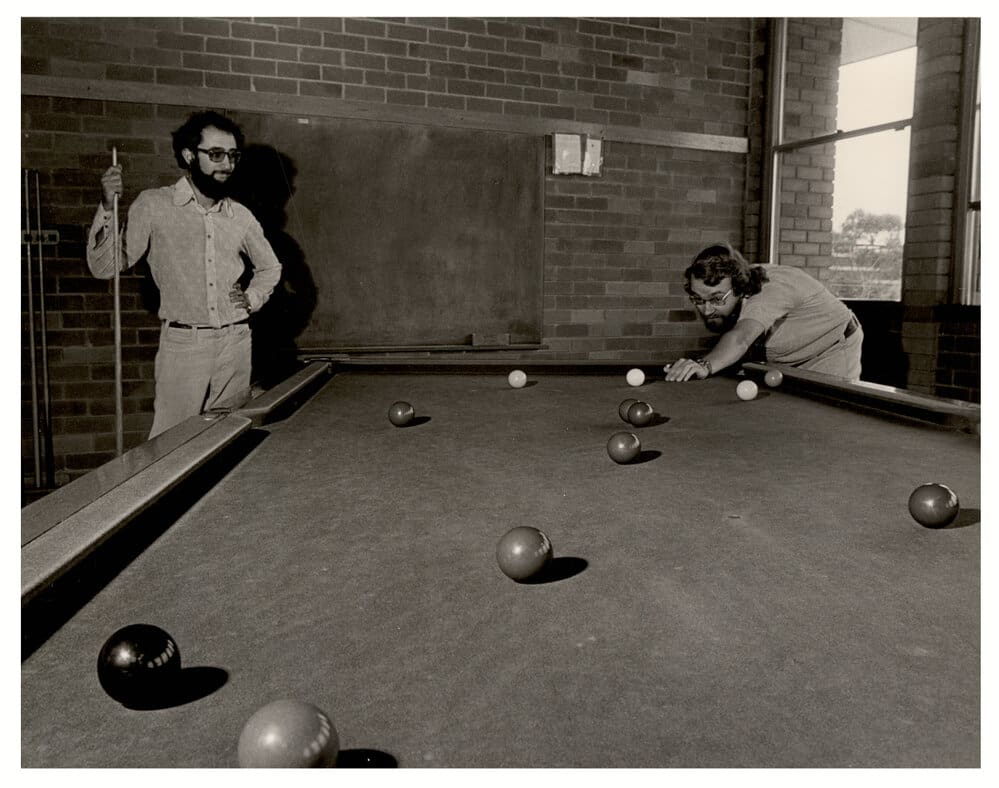

Of equal importance was the Wool Room, which sits at the centre of the Rotunda and was host to (according to rumours) “epic” parties, as well as the famous yearly International Night (“I-Night”). This decades-long tradition saw performances planned and choreographed by the residents to celebrate their many cultures. Of similar importance was the rooftop balcony, where many a summer drink looking over the University, Chippendale, and the city was enjoyed. As was the pool room, the TV rooms, the communal library, the meditation room and the gym.

This is why one of the first questions the IH Council had for the University when changes to the House’s structure were mere whispers was whether the dining hall space would be preserved. It’s also why many people expressed complete dismay at the University’s suggestion that the Regiment was adequate for the House’s residents to be moved to. It doesn’t have a communal dining hall, and severely lacks spaces like the Wool Room, which allow for social traditions to continue and develop. Strong IH opposition to the Regiment site option led the university to put up another option for the Abercrombie Street student housing project to temporarily set up its operation there, but it too lacked a common dining room.

International House is an institution with a social goal. It fosters friendship opportunities for international students who are often foreign to the University, and opens the minds of domestic students who have grown up in a globally isolated and parochial Australia.

The House’s cultural impact leaves a sense of purpose and dedication with its residents, who often go on to become active in the House community for many years, through the Sydney University International House Alumni Association. Across the world, during any given month, you can find IH Alumni lunches and events. The alumni of the House are active in its community; it is an experience one is eager to share with others.

In the 70s, one ex-student felt that international students should have the opportunity to get out of the city, and organised for the alumni to build a log cabin a few hours out of Sydney. Right up until International House was boarded up, its staff sacked, and the remaining students sent packing, there was an annual stargazing trip to the cabin organised by alumni, where cross-generational stories of the House were shared.

With all this in mind, it’s hard to understand why International House was closed. It is a hallmark of 60s architecture, and, in the last six decades, has developed traditions unique to the 6,000 residents who have come through its doors.

What’s more unclear is the University’s intended goal in redeveloping the International House site. Their own policy states that a building should only be demolished when it has “reached the end of its useful existence.” A clear case of how International House has reached this is yet to be made, nor is there a material plan for future buildings, beyond the ‘decant and demolish’ being applied to current structures. A report prepared by a structural engineer found the building to be in a sound structural state.

If the proposed hope is to develop higher density accommodation at the site, then the plan is at huge economic and environmental fault — to abandon the building entirely is seemingly devoid of logic.

Harry Bergsteiner provided Honi with a plan he presented to the University in his capacity as a member of the International House Council, which outlined how the House could be economically rehabilitated, its acknowledged deficiencies (old lift, failing services) rectified, its heritage preserved, and its residential rooms increased in floor space. The plan projected an expenditure which saved 40 per cent on the estimated costs that a knock-down rebuild would, and it didn’t even require people moving out, with construction taking place over the summer break. The University did not respond to this plan, other than to state that the proposal was complex, difficult and risky.

Harry also highlighted the intellectual dishonesty that a knock-down-rebuild would represent for a University ostensibly committed to sustainability.

“One of the things that architects are saying around the world is if you don’t need to demolish, don’t, because the embodied carbon which is already in the building is wasted.” Embodied carbon is the term used to describe the existing emissions and carbon footprint of a structure. “The third biggest contributor to global warming is concrete,” he explained.

As Harry outlines, the current situation for International House, particularly the lack of clarity on the University’s part, leaves a lot of room for questions and little hope for preservation of the House’s unique and ongoing history. However, we should have faith in the deep care and passion held by alumni, who are unwaveringly committed to ensuring there are future generations who get to experience what they did.

Places like International House are few and far between; knocking them down does irreversible damage. Students must not just roll over and watch them go.