War, in a vacuum, is abhorrent. It is the coordinated murder of thousands, sometimes millions, of people, in the hope of conflict resolution. And yet, the world has seen no shortage of wars. Sometimes, groups enter wars out of necessity, as a last resort against violence or oppression. Other times, nations formally enter into war, committing their own citizens to the conflict and sending many to their deaths. Justifying this — and, further, persuading a country’s own citizens to enlist for such a dangerous effort — requires that those citizens think of war not as abhorrent, but as necessary, as moral, perhaps even as heroic.

To do so, governments and public figures rely heavily on language and rhetoric to persuade a nation of war’s value. This is especially true when the citizens of said government are not otherwise at direct or immediate risk of experiencing the conflict, and entry into the war is purely political. In this article, I’ll explore the linguistic and semiotic history of Australian war propaganda — both the familiar twentieth century posters you may have seen in your history textbooks, and in the language used by contemporary warmongers.

Let’s start with the one of the first conflicts that Australia as a federated nation had the chance to enter: World War I. It’s worth noting that, just as with the other conflicts in this article, Australia was geographically isolated from the bulk of conflict. That is, Australia did not enter WWI for fear of being attacked; rather, it entered to support the United Kingdom as a member of the Commonwealth. The propaganda posters were thus a key part in convincing the Australian public that entry into the war was worth their own lives.

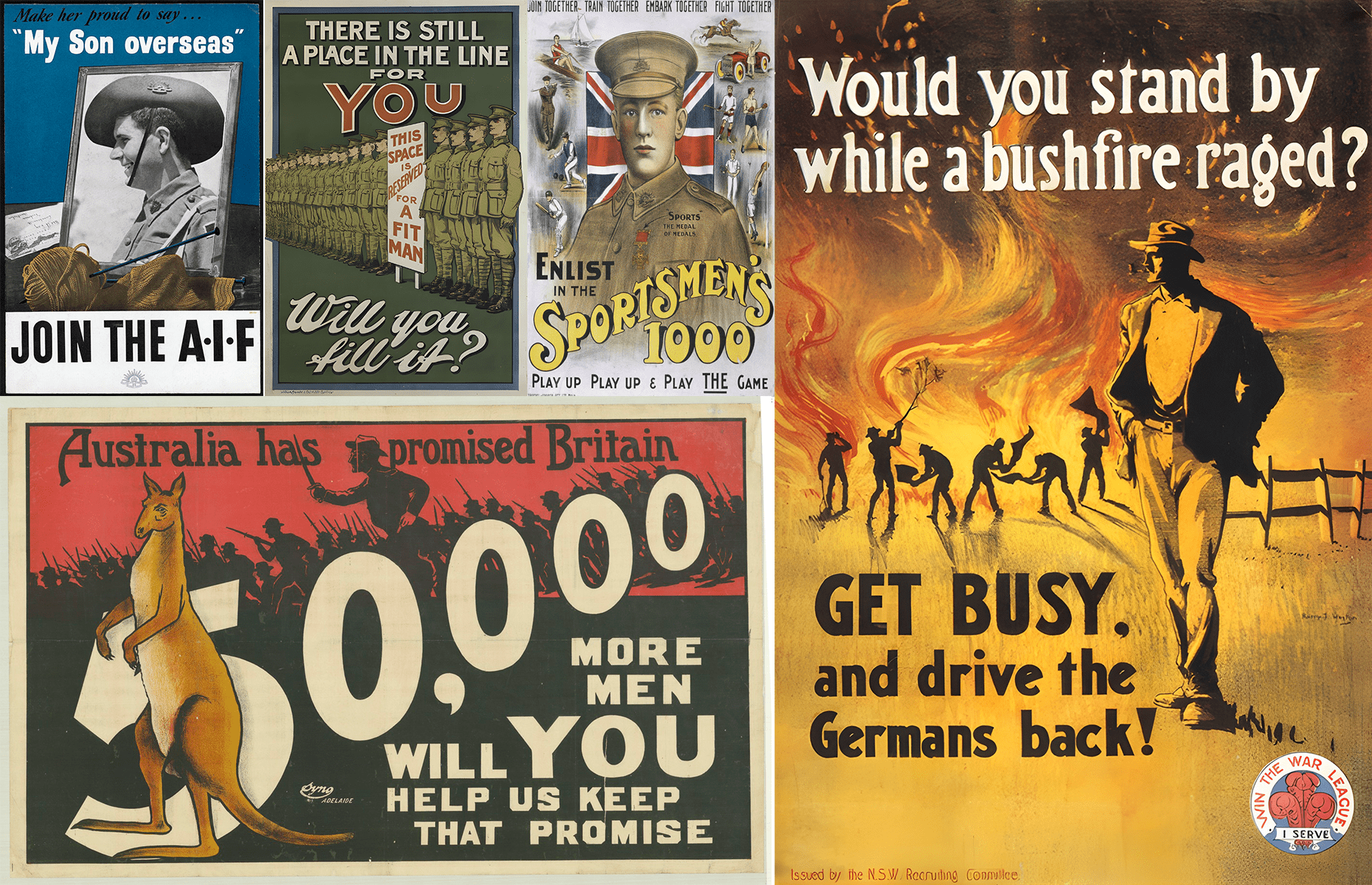

In propaganda posters, there are two noteworthy recurring grammatical features. First, imperative constructions, which demand something of the reader (as opposed to recounting an event). These can be identified by an absence of an agent in the core verb construction. Examples from posters I observed include single imperatives, such as “Enlist now”, and imperatives in sequence, like “get busy, and drive the Germans back!” and “Don’t stand looking at this. Go and help!”. They often featured exclamation marks to signal urgency typographically: “Enlist!”.

Rhetorical questions also featured frequently; questions that are asked with an answer the reader understands as implicit. These are powerful, as they not only further communicate urgency, but their answers are so common-sense and broadly understood that to deny them is to go against the mainstream, potentially incurring shame. Examples include “Would you stand by while a bushfire raged?” “Won’t YOU come?” (their emphasis), “Must it come to this?”.

Lexical and semiotic choices include the foregrounding of camaraderie (“Join Together Train Together Embark Together Fight Together”, and images of soldiers in lines surrounded by peers) and urgency (referring to bushfires, to calls that imply a need for response). They often include references to general Australian values or iconography — an image of a kangaroo, references to “the surf” and bushfires, a plea to “help us keep that promise” — and the suggestion Australia was under attack, such as one poster which depicts Australia under the shadow of a German soldier’s hand.

Australia’s entry into World War II was also motivated by support for Great Britain. However, the perceived threat of Japanese invasion due to Japan’s aggression in the Pacific was at the heart of many Australians’ decision to enlist. As such, while employing much of the rhetoric of WWI propaganda, there was an increased emphasis on Australia’s geographic vulnerability to attack at the core of WWII propaganda. Many of the features I observed in posters about WWI were also present in those in support of WWII, with a few noteworthy additions.

First, although rhetoric and imagery suggesting Australia was under threat is still present, the face of that threat has changed. One poster depicts an oversized Japanese soldier moments away from setting his boot on Australia; another describes Australia as “ringed with menace” and depicts it as surrounded by boats bearing the Rising Sun flag. The ‘Yellow Peril’ narrative constructed by this imagery is an example of propaganda establishing a clear ‘other’, compounded by the choice to represent enemy forces with a single person pronoun: “He’s coming south”. In doing so, the posters define the enemy as a discrete entity, implicitly characterising it as identifiable and excisable. Lexically, many of the posters featured language relating to victory — “change over to a victory job” — and high modality language, denoting a sense of certainty: “It’s fight or perish”.

Posters and rhetoric alone cannot account for Australia’s contributions to both world wars. Principles like justice, honour, fear of the unknown, and unity all exist outside of the linguistic and semiotic choices of the government. In creating this propaganda, however, the public’s fears and values were affirmed and directed towards a clear end goal: enlisting and supporting the war effort. Although we have not seen such stark propaganda for enlisting in recent decades, this strategic redirection of concern and morality is far from historic.

In 2001, after the 9/11 attacks, the United States entered Afghanistan and began a decades long occupation. Australia entered in October of that year. In an address to the Australian Defence Force, then-Prime Minister John Howard defended his decision to follow the US into war. He reduced the enemy to the single, knowable figure of Osama Bin Laden and used single person pronouns throughout the speech. He appealed to Australian values, saying Bin Laden hated “individual freedom, religious tolerance, democracy,” and claimed that enlisted soldiers would “have all the support the nation can give them”.

Howard positioned the 9/11 attacks as a threat to Australia: “We were all the targets… September 11 was an attack on the right of Australians, especially young Australians, to go about their daily lives and to move around the world with ease and freedom and without fear.” He made references to victory — “There is no doubt that the coalition forces will win” — and used consistently high modality language to create a sense of certainty and urgency: “the parties must return urgently to the negotiating table”, “A solution must be found”. Although not as blatant as posters caricaturising Germans or the Japanese, Howard appealed to the same emotions that past pro-war efforts did.

My conclusion is not that the government was solely responsible for pro-war rhetoric, or that people were wrong for resonating with the messages they received. Instead, I wish to emphasise how important it is to be critical of the language and symbolism used by those who may have an interest in stoking conflict. Propaganda need not be spelt out with bold letters and exclamation points; rhetorical choices can function just the same.

In his time as Prime Minister, Scott Morrison was a vocal critic of China. He positioned them as a threat to Australia as a “free, democratic, liberal country”, and blamed them for the deterioration of relations in the Pacific. He has identified Xi Jinping as being at fault for tensions between the two nations. Words are powerful — pay attention to why they are being used.