When I was introduced to sex ed for the first time as a kid in Year 6, I was directed to two books: one called Secret Boys’ Business, the other Secret Girls’ Business. Both were aimed at children, introducing them to the confusing and sometimes confronting parts of puberty — how your body changes, how things like menstruation, pregnancy, and erections work. Despite being presented as companion texts, aimed at teaching young boys and girls the same basic principles about their body, the former book was twice the length of the latter. Eleven-year-old me had only 32 pages of quirkily illustrated information about the confronting things happening to my body, while the boys in my class had 64.

There are a plethora of problems that come with under-educating people about their bodies, especially in the context of sex education. Improper or inadequate sex education leads to young people not understanding safe sex and possibly getting hurt. In a broader sense, though, it doesn’t equip people with the knowledge — or the language — that they need to take care of themselves, and to advocate for themselves medically or legally. When we deprive people — especially those assigned female at birth — of this vocabulary, we put them at risk. Language is a crucial part of healthcare.

First, let’s explore the linguistics underpinning this issue. Unsurprisingly, it’s hard to have a conversation without words. We build meaning with words and the definitions we understand them to have. It’s also hard to have a conversation with a limited set of words — if you want to express something but you don’t have a word for it, your explanation tends to be less precise, less streamlined. This goes beyond not being able to find that word on the tip of your tongue. It extends to an entire school of linguistic thought known as the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis.

The hypothesis is that our understanding of the world is filtered through the parameters afforded to us by the languages we speak. In his work as a chemical engineer for an insurance company, Whorf noted that English speakers misunderstood gasoline drums marked “empty” as containing nothing, rather than having been emptied of gasoline but still containing flammable gas, leading them to carelessly light cigarettes around such drums. Because English does not distinguish between both senses of “empty”, speakers don’t either. This correlation between the words we have and the way we understand words is also evident in how we identify things. Empirically, it’s easier to notice things with names you’re familiar with. I can easily identify when I feel sad or happy, because I’ve used the words “sad” and “happy” since I was a little kid. It is much harder to describe emotions which English doesn’t have neat words for, so I don’t consciously feel those nuances as much as I otherwise might. I didn’t really notice how often I felt déjà vu until I learned the term. Hence, a speaker of another language with a different set of words for emotions may have an entirely separate experience to me; the resources they have at their disposal are different. Our world is shaped by the words we have access to.

This includes the words we have for our bodies. The repertoire of names we have for body parts shapes the way we see our body, and the way we talk about it. Although the English words we have for body parts tend to be fairly comprehensive and standardised, that is less true for areas of the body we consider more taboo, such as genitalia, which we sometimes opt to refer to euphemistically.

While we use euphemisms and informal reference terms for body parts all the time — like calling your head a “noggin” — it’s unique that euphemisms and informal terms seem to be a preferable mode of reference for genitalia. This, I think, is especially true for references to female genitalia.

The words we have for female genitalia are broad at best and uncomfortable at worst. After anonymously surveying some AFAB people on their views on such words, a few trends emerged. The word “vagina” seemed to be preferred in conversational and medical settings, such as when talking to a doctor. Etymologically, “vagina” comes from a Latin root meaning “sheath” — something which a sword can be inserted into. It is not lost on me that even our most “neutral” word for genitalia is shaped by the way men interact with female bodies.

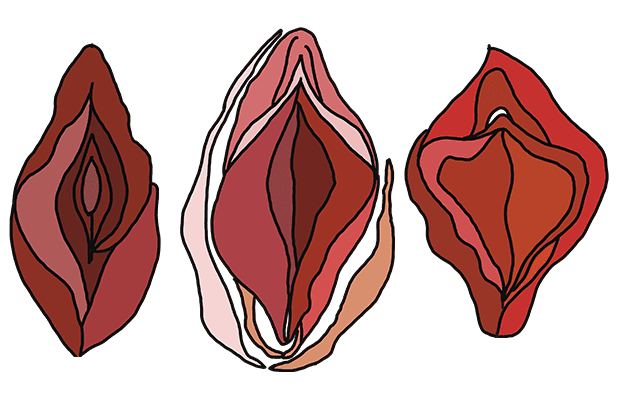

As one respondent noted, however, “vagina” is oftentimes misused. Anatomically, it refers to the internal parts of female genitalia, with “vulva” being the term for the external parts, but I — and most of the respondents I spoke to — only learnt this later in life. One respondent lamented the lack of a clear, all-encompassing label for female genitalia without the clinical or medical tone of “vulva” or “vagina”. These words sound awkward in casual conversation. In practice, they are often misapplied.

The euphemisms we have for female genitalia are equally awkward. Respondents identified truncated forms of “vagina” like “vag” or “vajayjay”, which evoke frustration: “an over the top euphemism is just annoying, because it’s not something that should invoke humour.” Others suggested “pussy” as a preferred term in casual and sexual contexts, which possibly comes from the Old Norse “puss”, meaning pocket.

The last term that came up in these discussions was “cunt”. “Cunt” stems from a geographical origin, being used to describe topographical features like gulleys or clefts, but has strong negative connotations, considered by some to be the most offensive word in the English language. Although Australian slang treats the term with less trepidation than other dialects, it is still used with negative connotations. Both “pussy” and “cunt” are used to deride and demean. It is not uncommon for words referring to taboo body parts to be used as insults — “dick” and “asshole” also come to mind — but “pussy” and “cunt” carry the unique pejorative connotations of weakness and shame, rather than just being a target of disdain.

The repertoire of reference terms for female genitalia that most AFAB people have ranges between misapplied medical terms and shameful euphemisms. This makes it hard to advocate for yourself in a healthcare context. How can you describe a symptom or a pain if you don’t have a word for its location? How can you understand what a doctor or gynaecologist is telling you if they’re using unfamiliar terms?

Furthermore, it steeps discussions of female genitalia in shame. If the only word you know for your genitalia is pejorative, you’re unlikely to bring up problems with a doctor in the first place out of embarrassment. This can be deadly. It can lead to AFAB people receiving improper or inadequate healthcare. This also applies in legal settings: feeling shame when talking about genitalia, or not having precise language, deters people from speaking to law enforcement or counsellors about legal issues involving them.

If Sapir and Whorf are correct, and we filter our world through the words we know, then the gap that exists in terms that describe female genitalia is devastating. We can — and must — do better to equip all people, young and old, with adequate and shame-free terms they can use for some of the most intimate parts of their lives.