Descending the Music Cafe’s stairs, we were met with tinsel rainbows, an intimate group of Conservatorium students, and two gay musical icons who have breathed life into Sydney’s queer scene throughout the 80s and 90s.

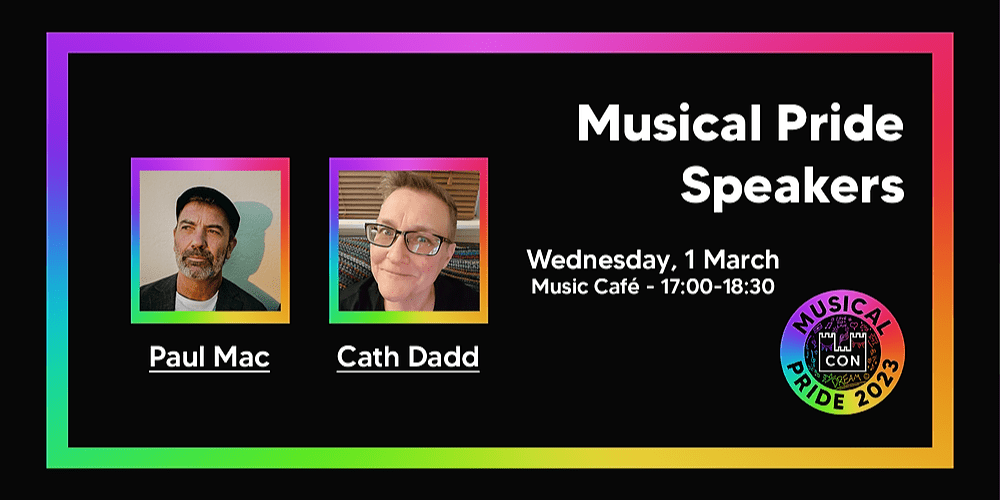

The two were Paul Mac — an ARIA winning musician who collaborated with Silverchair’s Daniel Johns and danced beside George Michael on Oxford Street rooftops — and Cath Dadd — Director of Music at the Joan Sutherland Performing Arts Centre; a fellow Westie; and an Opera Australia prodigy who casually worked alongside Simone Young.

Their musical excellence is testament to the defiant nature of gay artistry.

Celebrating pride by having this showcase became an acknowledgement of pain once felt, now seemingly forgotten amongst a younger queer community.

Mac began by justifying his presence, listing his achievements, explaining his queerness, and recalling his memorable speech upon accepting an ARIA award in 2002.

“This track was made at home in a bedroom, so anybody can do it,” said Mac, “all the DJ’s… radio stations, all the ravers, all the ecstasy dealers.”

This recital gave way to a narrative of what Oxford Street once was, during the decades of gay bashings and cruising. We were liberated from the queer vulnerabilities of hostile Sydney in the 90’s, with this revisited imagination of Darlinghurst and Newtown during the golden decade.

Mac reminisced, “whenever I got to Newtown, it felt like these were my people, my community, my neighbourhood; ugh, I’m home!”

Our excitements grew with his reminiscence of parties, drugs and sex — the holy trinity of queer youth amidst a nightclub scene — and the dissent and hedonism which flowed through the pulsing veins of this period in queer history.

Yet, so had our anxieties.

Mac reflected on the passing of George Michael and the emptiness felt within our queer community. Having later erected a mural called ‘St Michaels’ featuring religious iconography, the place lived a continuing queer legacy. Sometimes ornamented with candles and flowers, lone people with speakers connecting with his music, or as a Grindr meeting place – what was left of Michaels’ impact was untouched by taggers, and became a preserved space.

Its eventual violation in the form of scars of black paint rolled by the Christian Lives Matter group was a signature of the ever-present threat of homophobic violence.

Paul recalled his anxiety, “this is getting scary, this is our home.”

While discussing the rises and falls of the queer experience in Sydney, Mac’s fears still felt so raw and provocative.

He closed with a presentation of a score he composed; performed by a community orchestra at the Sydney Festival in 2021. The drama, The Rise and Fall of Saint George featured a song, There’s Nothing Religious About This –– inspired by video footage of a vandalist coating the mural in black paint, while exclaiming his religious defences.

The energy in this space shifted dramatically in this decline of spirit; the fragility of gay expression had been made vulnerable by this very real attack. Though the legacy of the wall has not been forgotten; there was a query by a student;

“What’s the wall like today?” –– they asked,

“I think it’s SOPHIE now, isn’t it?”

Paul smiled; a realisation of hope gave momentum to his closing. A continuing legacy set by Michaels has been realised, now with SOPHIE –– a musical figure younger queers are familiar with. It felt like Paul’s reminiscence of the once energetic queer Sydney had not been lost; but reimagined in this new form.

After intermission, Cath Dadd revived our spirits, bringing alive the Oxford Street of old.

“You’d start at Patches, across the Exchange, and go to Flow’s Place. They called Oxford Street the Golden Mile,” Dadd recalled, listing names the audience of Gen Z uni students found unrecognisable — The Pop Shop, The Soup Kitchen, Remo’s! — yet some points continue to resonate: “You can’t talk about Oxford Street without mentioning illicit substances!”

She then exclaimed a point seemingly timeless for the Sydney queer community, “You could go there and you felt at home. As soon as you were on that strip, you felt within the community; because it was visible!”

Her talk truly formed a conclusion to what Oxford Street once was; a euphoric hub inspired by illicit drugs, house music and drag, manifested through her own passionate tone.

Though, again, we were reminded of the struggle inherent in the queer experience. We could feel the gravity of the HIV/AIDS epidemic as it tormented a vulnerable queer community.

Dadd explained, “You could tell they had it just by the look in their eyes.”

She recalled people rapidly losing weight, blotches forming along their skin. Months later, you would never see them again. The terror of the epidemic came alive. Random deaths were an ever-present thought in the midst of a scene founded upon escapism.

“But in those days, we were fighting for our lives (…) that’s how we survived. We danced through the 80’s, the 90’s, through HIV.”

To hear these people speak was to realise that there can never be a true reflection of queer history without the anxiety of bashings, institutional neglect, and lovelessness we have once; or continuously felt. History is living, and the importance of recognising the struggles experienced by queer Sydneysiders only some decades ago must be realised.

Dadd closed with optimism, in reference to us, the younger queers sat in front of her, “these guys should only know joy. Yes, we went through that, but you shouldn’t have to.”

It felt we, the audience, were given freedom; owing our partying and drug-taking to those before us — who gave birth to these very traditions we call gay culture.

By the end, the empowerment we felt was awesome. The intimate space was like storytelling in a living room; where anecdotes were shared over lounges with swaying moments of seriousness and laughter –– like listening to an aunty and uncle share stories of their younger years; a moment where you realise older people once did things we think only twenty year olds know.

It made us think of how ‘history’ as we understand it separates us from memories of queer struggles within a distant imagination; where the bashings of 78ers, or the mass deaths of those infected with HIV/AIDS seems unparalleled to our present reality. To hear Paul and Dadd speak vividly of these things we’d think to only read in textbooks, or hear in documentaries, was truly grounding as a gay man in 2023, who has the freedom to open Hinge or Grindr on an iPhone. It seems almost impossible to imagine a time where queer spaces and connections could not exist safely both physically and virtually.

What came from these talks was raw familial love, by these strangers who a mere two hours earlier I had never met. This talk was a realisation of the foundation of Sydney’s queer community; a place of belonging for those who have not had the security of love like their heterosexual counterparts–– where we feel a pride in divergence from the social norm.

“God knows, if those buildings could speak,” Dadd closed.