There can be no societal progress while some remain in fetters. There can be no change whilst silence pervades any opportunity for justice. Shirin Neshat, an Iranian-born visual artist, uses her art as a channel that speaks to and amplifies the voices of those who so often remain silenced at the behest of exploitative powers. I had the privilege of attending the opening of her exhibition, ‘The Fury’ (2023) at Gladstone Gallery in New York, where Neshat confronts her audience with a sixteen-minute, double-channel, monochrome film where she intimately explores the lasting effects of the physical, emotional and sexual traumas that female political prisoners often experience.

Using two screens placed directly across from one another in an unspoken communication, Neshat opens with a close-up shot of an Iranian woman’s face in sormeh eye makeup—an ancient Persian style of eye makeup used to embolden the eyes. Her gaze locks with a man seated in military uniform on the opposite screen; the smoke of his cigarette hazing the clarity of the frame. Throughout the film, Neshat utilises these two screens to show the different power dynamics and perspectives that ensue between a torturer and their victim, also noting the disparate realities of femininity and masculinity within patriarchal cultures.

When I first watched the film, immersed in the images on either side of me, it initially gave rise to feelings of conflict regarding my Iranian identity; in that the deeply-rooted sexism and violence that has so often permeated the experiences of my friends and family has only ever been a numbing deterrent of my engagement and sense of connection with it, even amongst all the beautiful elements of Iranian life, culture and history. See, ‘The Fury’ shares a story I’m all too familiar with.

My Grandmother, Maman Bozorg as we all knew her, was imprisoned in the political Evin Prison in Iran in 1983 for 2 years in the aftermath of the 1979 Islamic Revolution. There are feelings and experiences I will never understand, but can imagine through the stories she would share: of the dehumanising and incessant torturing; stories of the friends she would make, many of whom were taken and killed, never to be seen again; stories of a month-long solitary confinement, designed to mentally break her, and the darkness and thickness of dust that lined that cell.

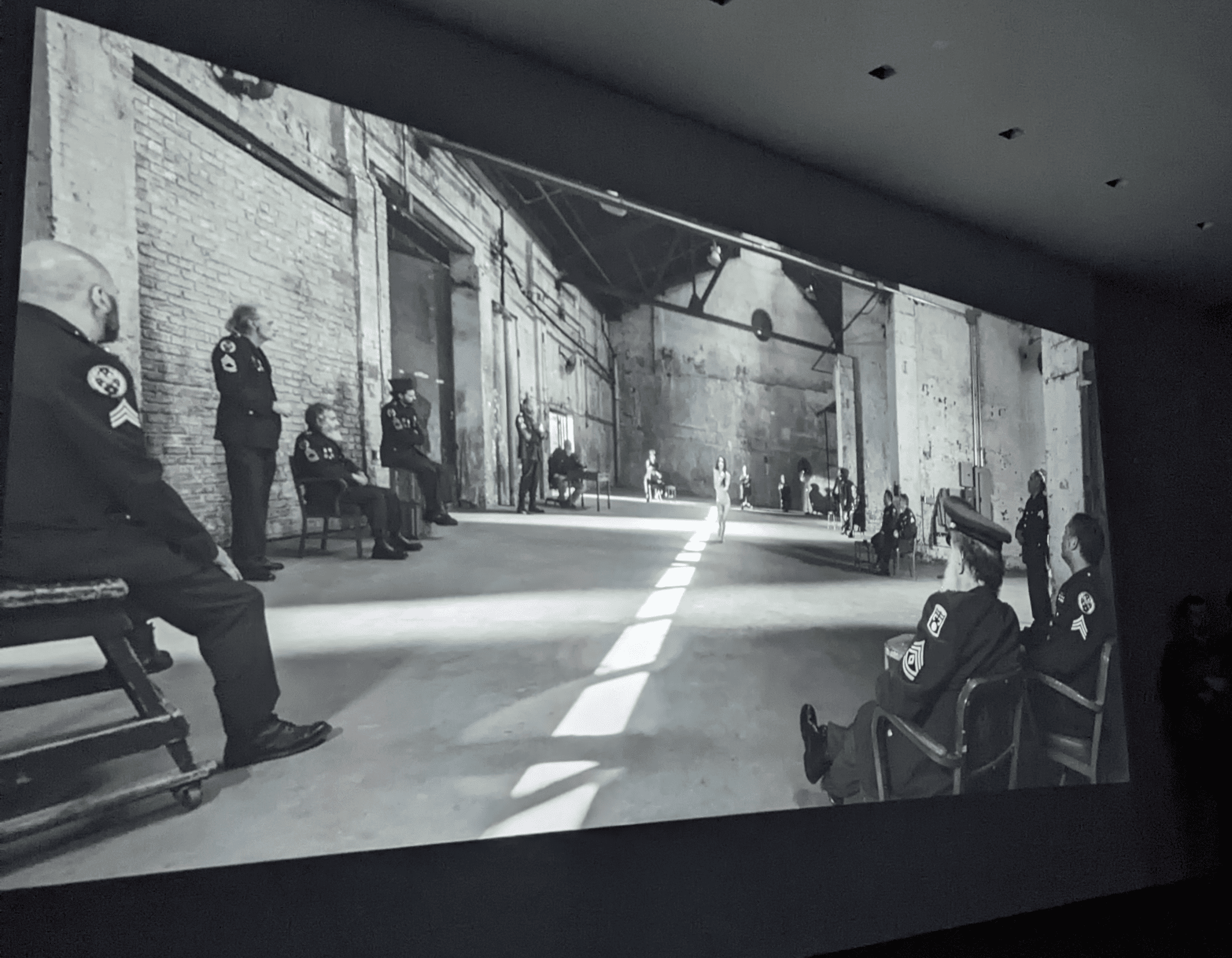

Drawing from experiences remnant of my Grandmother’s, Neshat looks at the female body as a contested site where desire and violence, shame and power, vulnerability and strength unite as contending forces. In ‘The Fury,’ this is conveyed when the female protagonist can be seen in a warehouse encircled by a group of men in military uniforms, their facial expressions blank but their glares filled with unsettling violent desires projected towards her. It is here that the horrifying scars of torture that cover her body are exposed. She tries to dance, spinning countless times with her arms outstretched as though pleading for succour from the men who remain so close to her, yet unmoved by her anguish. Her ailing body eventually collapses to the floor, though she is able to regain strength and eventually leave the space.

This potent, yet deeply confronting scene conceptually reflected my Grandmother’s experiences. I can only wonder what it felt like for her, for all the women who have experienced this, to have these memories and scars shadow them even as they build a new life outside of prison, outside of Iran. I remember Maman Bozorg sharing how she could not physically walk due to bastinado torturing—which involved lashes on the feet with a cable—and sharing the vile comments that the guards would make when she was handed meals or showering. Amidst this, however, she always shared her hope in humanity—that little by little, there would be change.

By a miracle, the person in charge of the prison had a dream about my Grandmother’s innocence and out of fear, hastened to have her released and removed from his conscience. It was also around this time that she herself had a dream that she would travel to distant places, never thinking this would mean beyond her homeland of Iran.

During a time when so many political prisoners were killed, there were very few recounts of what was actually happening within these prisons. Maman Bozorg realised that if she was not courageous enough to voice these harsh realities to the world, no one would ever know the truth. And so she would share her stories with family, friends and news outlets, eventually travelling across almost every continent sharing the gruesome realities and humanitarian injustices that prevailed, and still do, within Iran’s political prisons.

Still, these stories were also ones of hope in humanity—that action can be taken on both small and large scales to constitute beneficial change. We have and continue to see glimmerings of this now with the Women, Life, Freedom Movement.

Though ‘The Fury’ was completed in June 2022, its release is no doubt timely. The Movement has seen people in Iran and globally, irrespective of gender and nationality, coming together in the promotion of gender equality and protesting against the systematic oppression and persecution of women.

What is perhaps key in sustaining movements whereby change can occur is, first and foremost, the consistency of communication. If we do not continue to speak about these issues, action cannot be taken and thus change can in no way occur. Neshat’s film opens a dialogue to her audience on the institutionalised sexism, moral perversion and power dynamics that encourage violence globally, especially in prisons which are so often an arena for horrific acts.

My Grandmother realised the potency of sharing truth and promoting social justice, which involved sharing her experiences from Iran. Sharing my family’s story is a call to action. An urge for all to continue to speak about global and local injustices. Though it may not appear obvious, they do directly and indirectly affect us all. Again, there can be no societal progress while some remain in fetters.