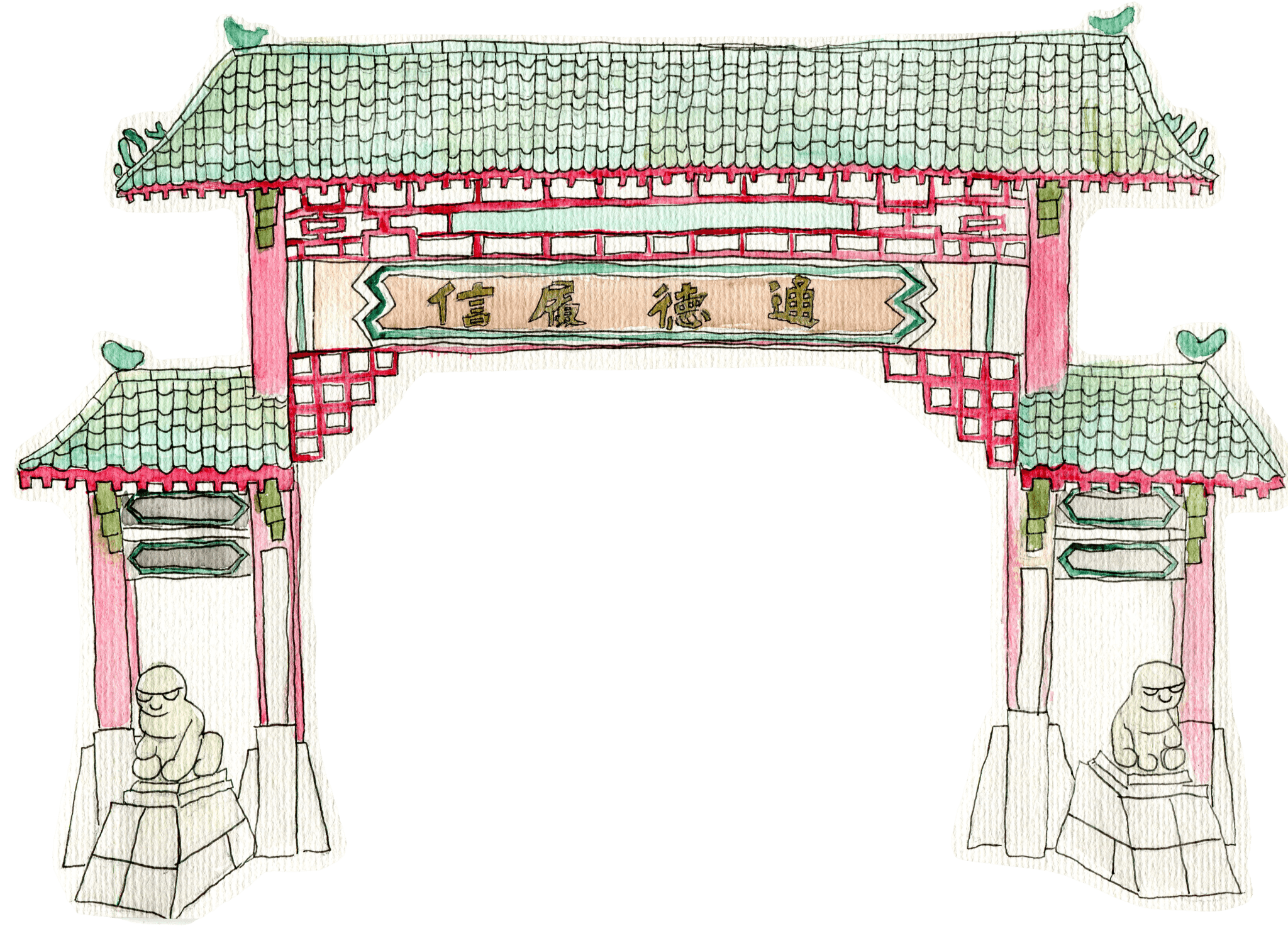

The Sydney Chinatown from my childhood memories was always alive and beating. There used to be many colourful street performers on Dixon Street, and the queue for Emperor’s Garden cream puffs would stretch for eternity. People would take photos of the giant archways whilst leaning against the stone lions guarding them. The scent of dried abalone permeated the atmosphere — an ingredient which represents prosperity.

Chinatown is not a timeless exotic town square separated from the rest of Sydney. Rather, it is an institution shaped by people with diverse identities interacting with one another in Australia’s unique cultural landscape. Professor Kay Anderson, in Chapter One of Chinatown Unbound says that Chinatowns across the world are conventionally viewed as: “idiosyncratic oriental communities amidst an occidental urban environment.”

This understanding of Chinatown suffers from several issues. First, in viewing the institution as an essentialist Chinese one, it ostracises the community and reduces the identity of Chinese immigrants solely to “non-Western”. Second, it overlooks the complex interaction of history, culture, and identity necessary for such an institution to form.

Chinatown is not the product of any single group or specific event, rather it is the product of a unique landscape occupied by a myriad of diverse identities. Instead of a sliver of a foreign place, Sydney Chinatown should instead be viewed as an institution deeply embedded with the rest of Australia.

So place your finger on Sydney Chinatown with me, feel its slow trembling pulse, and we will see Australia’s past, present and future.

- Chinatown’s past is Australia’s past:

Chinatown began as the product of the political and cultural forces at play in Australia during the 20th Century, not least the White Australia Policy passed in 1901. This policy reflects the then white nationalist attitude of the West, where many Chinese Australians were forcibly deported and those who remained were antagonised.

Under this inhospitable climate, many fled to Dixon Street — at the time, it was one of the poorest areas of the city where the small population survived with the little they had. During this time, they started to turn the once inhospitable Dixon Street into a home, paving the way for what is now Chinatown. Chinese locals started setting up clan associations to look after one another, for instance, they bought buildings to turn into boarding houses to look after elderly Chinese men who had no family.

While Australia remained in the past, other Western nations started to race ahead by embracing multicultural policies during the 60’s. For instance, the US Civil Rights Act of 1964 banned segregation in the United States. For Chinese diaspora around the world, this tide of change led to money being spent in many Chinatowns across the world, turning them into popular tourist destinations.

However, Dixon Street was still treated like the ghetto of Sydney. In response to the development of San Francisco Chinatown, Sydney City Council representatives commented in 1972 that “one must admit to a sense of shame when one shows a San Franciscan our version of a Chinatown.” At the same time, the governing regime in Australia was being challenged with the economic rise of Asian powers and faced with the potential of being left behind if it remained isolated from non-European forces.

Australia needed to change, and it did. White Australia ended in 1973, under the Whitlam government, sending the country to embrace an era of multiculturalism. The authors of Chinatown Unbound wrote, “the logic of multiculturalism altered the positioning of ethnic subjects within the nation state: they were no longer asked to assimilate and hide their cultural differences.”

At the micro level of Sydney’s Chinatown, the City of Sydney began initiatives with plans like “beautify Dixon Street” and poured money into revitalising the area. The goal was to accentuate the area’s ethnic heritage: lanterns were added, decorations were installed, and a mall was later proposed.

The aesthetic profile of the area has often been criticised as “orientalist”. However, these perspectives can overlook the contribution and agency of the Chinese Australian community throughout this period of change. In fact, the most visually striking decoration of the street — the ceremonial front gate and stone lions — were backed and paid for by local Chinese residents. This entire process was also done with the consent of a Chinese Committee from Chinatown made up of local businesses.

The 1970s saw the continued expansion of multicultural policies. Chinese schools and community oriented organisations were funded. By 1997, Chinatown Unbound cites that Chinatown became the ninth most visited attraction in Australia.

Chinatown’s history is not confined to its geographical perimeters, and reflects the broader ongoings of Australia. Chinatown ought to be considered as an ever growing entity, formed and shaped by daily transactions, rituals and communications, and is tangled with its surroundings at every scale.

- Chinatown, unbound in Australia’s multiculturalism today:

Chinatown in 2023 is in a much different state than the flourishing destination it came to be. The once fierce lion statues guarding the front gate stand in silence and the neon signs of Emperor’s Garden Restaurant flickers meekly as if it is on its last breath. “For lease” signs are plastered on many windows, preventing passersby to peek into memories of a different time. As we mourn for yesterday’s Chinatown, which has declined further after COVID-19, the current situation offers us a bittersweet opportunity to cherish and reflect on Australia’s flourishing multiculturalism.

Today’s social context is very different from the 70s. Then, Dixon Street was home for the majority of the Chinese Australian community who had all converged from a similar working class background of Guangdong and spoke the same dialect. The street was designed according to their initiatives and taste whilst still being adequately called “Chinatown”.

However, Dixon Street is far from being representative of the Chinese Australian community today. Following the introduction of several skill-based and investment based migration schemes in the 90s, a wider diversity of Chinese people have settled in Australia. Many took their wealth built from China’s successful economic reforms under Deng Xiaoping and found a new home in Australia. Similarly, middle and lower middle class Chinese diasporas from other Asian countries like Malaysia, Indonesia, and Taiwan have also come here.

Chinatown, as a result, is no longer an exclusively China-town. The flavour in many Cantonese restaurants offered there do not necessarily resemble meals that Chinese mothers cook at home. Guangdong people do not make the same braised pork rice with the hint of sweetness from brown sugar as my Taiwanese mother would.

Different restaurants and businesses from a diversity of backgrounds have taken to Dixon Street. Other “Chinatowns” have also appeared in Chatswood, Hurstville and Burwood. Though Chinese Australians were once ostracised, today we embrace and appreciate Asian communities whether they be in Dixon Street or beyond — rather than considering the original Dixon Street Chinatown as in decline, we should see it as expanding.

- Chinatown — multiculturalism and capitalism:

Sydney Chinatown’s current state not only reflects the evolving social dynamics of Australia, it also sheds light on the consequences of the country’s economic changes in the past four decades.

Many recent changes in Chinatown correlates with the real estate boom which has made housing inaccessible for many people. Due to the visibility of Chinese investment, people have placed blame on the community for contributing to the housing bubble.

A lot of today’s old empty spaces in Chinatown are being revamped for real estate investments. The Sydney Morning Herald has reported that three new hotels have been proposed near Chinatown. The Urban Developer has also reported that the owners of the now iconic Emperor’s Garden Restaurant are ready to turn the space into a 14–storey apartment complex. This reflects an ongoing — albeit inconsistent — phenomenon over the past two decades that has seen the area and like many others across Australia, become real estate hotspots.

Hence, the increase of foreign Chinese capital in the Australian housing market has drawn media fascination and scrutiny. This includes businesses set up by first and second generation immigrants that offer services to foreign Chinese investors. Events in the early 2010s like the “Chinese Sydney Property Expo” held in Dixon Street also drew widespread attention. There has also been a focus on the many Visa policy amendments made by the government to appeal to the foreign Chinese investors, that see residencies given out without English requirements and age limits to those who have invested up to five and fifteen million dollars respectively.

This scrutiny is damaging to Australia’s multicultural landscape. A lack of differentiation between foreign and local Chinese buyers, reduced a wide and diverse population in Australia to a singular foreign entity. This bears many similarities to the attitude of White Australia, when Chinese Australians were solely considered as “the other”. It ultimately overlooks what the development of Chinatown truly reflects —– the consequence of domestic policy decisions, such as mortgage liberalisation and low interest, over the past four decades, overheating demand in the housing market.

The swiftness with which Chinese Australians have been made to bear the blame should be a reminder of the potential regressions into racial fear mongering.

- Conclusion:

No matter how people may separate Chinatown from the rest of Sydney, its fate is intrinsically tied to its surroundings. What happens around Chinatown shows up in physical changes on Dixon and Sussex street. Whether it is the addition of a new restaurant, or the demolishing of a building, it all relates to the broader happenings of Australia.

Likewise, Chinatown’s people — the Chinese Australian community — have always been at the beating heart of Australia. Whether it be a community in refuge surviving with bare means, or as prominent members of society, they have been part of the Australian story since the beginning.

Just like it did 100 years ago, Sydney Chinatown still lies across Dixon and Sussex Street.

Retrace the footsteps you took there as a kid with your parents.Turn right when you see Paddy’s Market and you will see the famous ceremonial gate and the stone lions guarding them. Place your hands on them, be gentle, they don’t bite, and in voices echoing from the past, they will roar:

“Welcome to Chinatown.”