Once, at a restaurant, in an entirely unrelated discussion, a friend turned to me and said, “you look like a nest person.” He was referring to something he’d seen on Twitter, a photo of a room with a pile of clothes instead of a mattress to sleep on. Although I do have a mattress, his observation wasn’t entirely wrong.

I have a fairly messy room. I always have. It’s not unhygienic — there’s no food or other organic matter — but it fluctuates from slightly untidy to entirely askew. I have always considered this a fault of mine. I grew up with endless instructions to clean my room, bargaining processes that traded a clean room for a social activity, and had jokes made at my and my room’s expense. I’m not so sure, however, that messiness is the flaw we treat it as. I think messy rooms are worth defending.

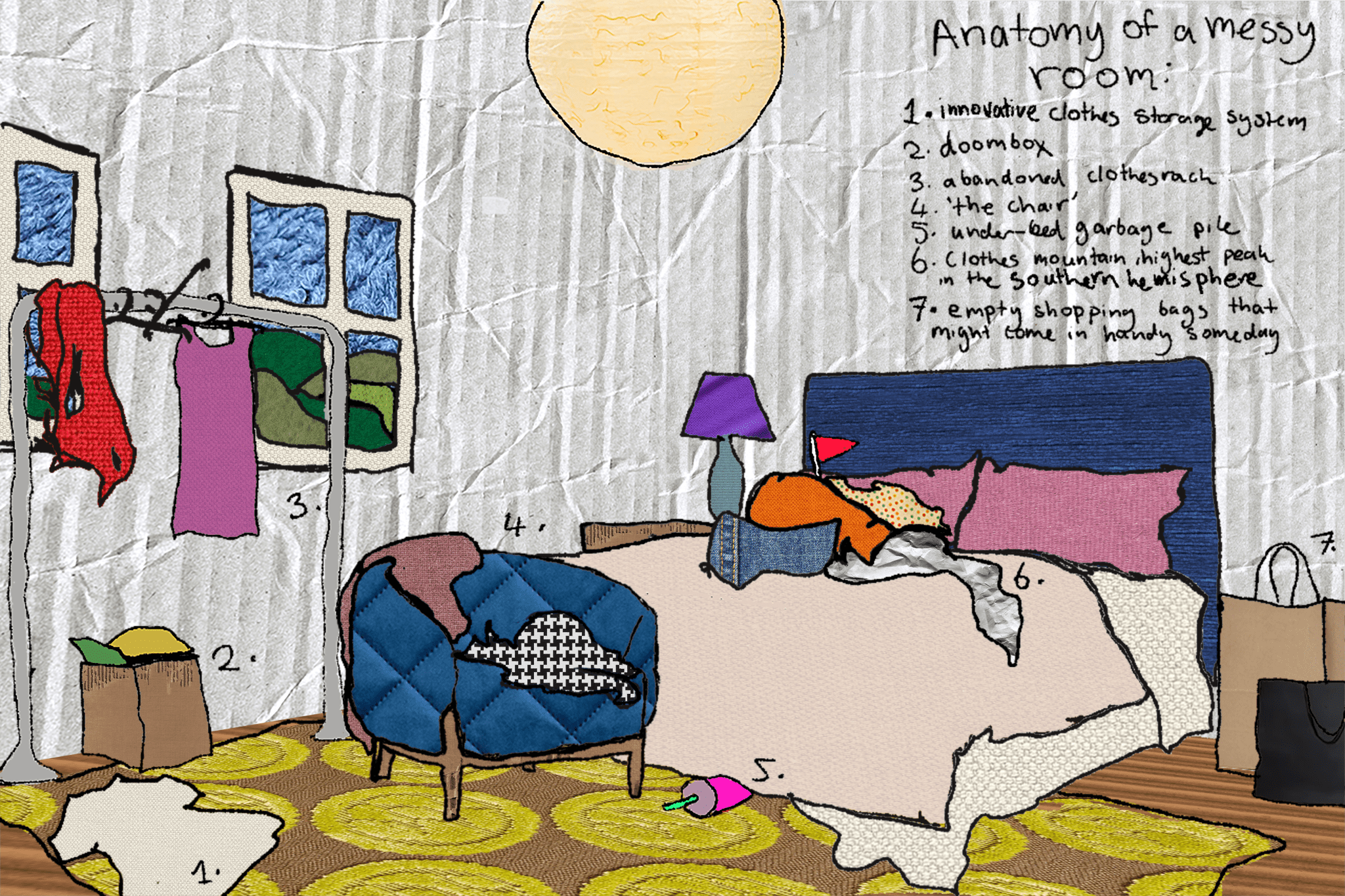

Our standards for tidiness seem arbitrarily restrictive. It is certainly true that it’s harmful to live in incredibly messy or unclean environments. Most untidy rooms, however, are not biohazards. Messy rooms usually have things out of place, such as clothes on the floor, cluttered surfaces, or a lack of organisation when it comes to storage. For most, this does not meaningfully impede their life. If I can find what I need, then not having a rigid organisational structure doesn’t bother me.

Even so, I feel a sense of shame associated with admitting how disorganised my room is. When I have people over, I apologise for the state of my room reflexively, even when I’ve spent ages cleaning it. Oftentimes, this apology isn’t a sincere expression of remorse, but rather a preemption of judgement. As though without flagging that yes, I’m aware of how cluttered my room is, my guest would assume that I’m ignorant of the disarray I live in. We ascribe a moral value to cleanliness — even likening it to godliness — and falling short of those standards is a moral failing. This condemnation seems based more in norms than in reason.

If we have such a strong cultural aversion to clutter, why, then, do our rooms get messy? The most obvious reason is this: some of us just don’t prioritise organisation. Cleaning sucks. It is repetitive and boring, and only lasts for a while until you need to clean again. It is easier to put things on your bed or desk than to meticulously file them away. Maintaining strict order takes time and effort, especially when, like me, you have hobbies like art or makeup which involve lots of bits and pieces. Leaving my paintbrushes out on my desk saves me time packing them away and unpacking them next time I want to paint, even if it means clutter in the interim. Some of us just don’t consider that additional effort a worthwhile use of energy.

Growing up, the mess in my room progressed reliably as the school term did, cycling between my post-holiday clean in week 1 and an explosion of study notes, stationery, and general chaos after exams. Cleaning takes effort, especially if disarray doesn’t bother you. The more I have on my plate, the less energy I’m willing to commit to cleaning. Of course, this includes university- and job-related work, but it also extends to managing any sort of mental workload. Existing is exhausting. Dealing with periods of change, burnout, and mental health can take a lot more effort than we realise. When I’m overwhelmed, picking clothes up off the floor is the last thing I’m worried about. The effort that cleaning takes compounds over time. Putting away paintbrushes doesn’t take long, but deep cleaning a room does.

This is where the shame associated with disarray becomes harmful. When my room is at its messiest, I am at my most drained. Feeling ashamed of my incapacity to maintain a tidy room doesn’t make cleaning more appealing, instead adding to the perceived mental toll that returning my room to cleanliness will incur. This shame is isolating and makes it hard to ask for help — if I believe myself to be uniquely and immorally messy, it’s embarrassing to admit that I’m incapable of cleaning up after myself. This can worsen one’s mental state too; the shame and magnitude of the mess around you can, for lack of more delicate words, make you feel like shit.

It’s also worth noting that the standards of cleanliness we often impose on our rooms are not designed for neurodivergent inhabitants. I spoke to several neurodivergent students who shared that the repetitive and ongoing task of cleaning a room was especially overwhelming for people with ADHD, autism, and depression. Mehnaaz, who has ADHD, says, “if I can’t organise every single thing in my room at once, then I can’t go inside.” Cinnamo explains that their depression can be worsened by mess: “when my room gets messy again, it impacts on my mental health because I’m stressed about cleaning it.” When sharing these thoughts with me, all of them couched their explanations with acknowledgements of shame. Eleanor described how she used to struggle with cleaning because of ADHD, leaving food or drinks out for too long, and tagged it with “[vomit emoji] I know.” The shame that surrounds mess is compounded when the reason for that mess is out of your control.

If you are struggling with controlling mess, it’s not your fault. Cleaning can be hard. The best I can suggest is this: set yourself a timer for fifteen minutes and try to clean throughout. Best case, you fall into a rhythm and can get more done. Worst, you just clean for fifteen minutes, and that’s still progress. It’s not a perfect recommendation, but getting myself up and cleaning, even if only for a few minutes, has been really helpful for combatting the shame that can come with extreme disarray.

Despite all this, I think a bit of mess is a good thing. My chest of drawers is topped with earrings gifted to me by friends, scented candles burned halfway down, cool trinkets from places I’ve travelled. The heels on the floor at the end of my bed were kicked off after a night of dancing. There’s a tea-stain ring on my desk from where I left a mug for too long, engrossed in an artwork that I stayed up late to finish. My bedsheet is never perfectly tucked in, as I kick it back out every night.

Tree swallows line their nests with discarded feathers. A feathered lining insulates their eggs and keeps out parasites; this adornment makes a nest liveable. Perhaps our rooms are more like nests than we realise — safe, lived-in places to offer us comfort. We should all be a little more at peace with chaos.