I’d indulge in the contemporary trope of beginning at the end, but this is a story that’s still being written. Its opening has blossomed outwards, but its climax is uncertain. Despite this, we can be sure of how it will end, or rather, of the two ways it will end: in total rebirth or complete destruction.

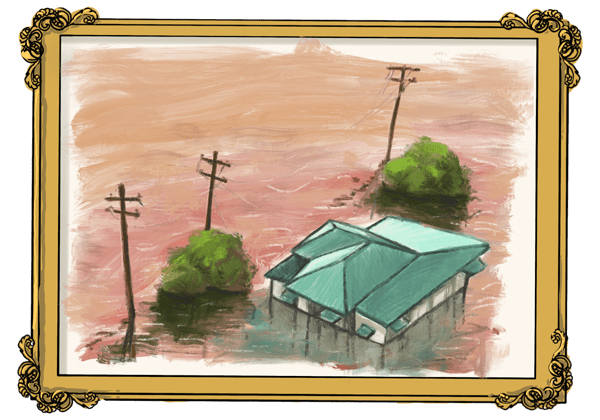

Instead, let’s begin with a time of immense noise. The media is a competition of noise, the volume (in every sense of the word) of each bulletin drowning out the next. This is a time of spectacle: noise punctuates all issues, from the environment to the economy. Picture a hurricane, a storm, a tsunami, a flood, a drought. Crashes, bursts, thunder –– now watch a market crash, a bubble burst, a thunder of applause.

This is a time of recycling: filmic remakes and biopics that poke at the corpses of dead stars, another fashion brand “collaborating” with a late artist, another Christie’s auction where a century-old masterpiece is brought out to complete silence, and the crowd applauds only when the hammer falls. The sound of money is thunderous, and it has induced the dominant culture-makers in developed, western societies to repeat itself and imitate itself to no apparent end.

This is all to say, there cannot be an avant garde in a society where economic interests have completely usurped cultural ones. The market produces what is profitable, and art (and by extension, film, literature, and all other cultural commodities) is most profitable when following what is tried and true, and therefore unoriginal. Arthur Danto notoriously proclaimed in The End of Art that we are in a post-historical period of art, bringing into existence works “which lack the historical importance or meaning we have for a long time come to expect.” Postmodern theorist Frederic Jameson wrote that “a truly new culture could only emerge through the collective struggle to create a new social system.”

Whilst these ideas –– post-historicism, postmodernism –– are many decades old, nothing has come since to definitively replace them as core cultural frames of the present era. It is true to say that the very nature of contemporary culture resists homogenised definition, but are we doomed to another lifetime of this unfixedness?

How will the humankind of the next century look back on this time, draw lines between our artefacts, and hypothesise on what name to label it? It won’t take a struggle to create a new social system to end the inertia of our self-loathing, self-regurgitating culture, as Jameson suggests. The next shift in art, its next breath of new life, is underpinned by the choice between looming environmental destruction, or environmental change.

The singular and most significant aberrance from the postmodern status quo has been through environmentalist cultural works.

Notoriously difficult to define and coneheaded as they are, we can think of postmodernism as a cultural shift from the grand, utopian narratives of modernism, to a scepticism of language and order that materialised after the end of WWII. Modernism was the era of movements: from Impressionism’s stained-glass renderings of middle-class life, to Abstract Expressionism’s rejection of representational integrity, each movement orbited around artistic circles and their world-shaping manifestos.

At its most extreme frontiers, from Modernity also came Fascism. The events of WWII shattered the grand-narrativist aspirations of Modernism, and uprooted the entire utopian foundations on which art had, for almost a century, founded itself on. Art making was displaced by two concurrent post-war forces: globalisation through the spread of multinational capitalism –– establishing global corporations as advertising and cultural hegemons –– and the spread of the television set, with the image overtaking the written word as a cultural dominant.

Advertising explodes into every aspect of our public and private lives; Disney comes to define the cultural age; Pop-Artworks like Warhol’s soup cans confirm the dissolution of the distinctions between art, marketing, and entertainment. We can no longer assume that cultural works bear sophisticated or world-altering meanings, because ornament and spectacle have been mobilised as distractions from the hollowness of most of the media that surrounds us.

This extends to how the media shapes our understanding of the environment, and environmental change. The vocabularies used to describe environmental issues in the media are far from neutral: shaped by distinct undercurrents of financial influence, shifting the phrase “making headlines” from figurative to literal. What is there to be said of “natural disasters” which are in fact consequences of human activities and climate change? The false balance fallacy created by giving climate denialists equal airtime as climate activists violates the real scientific consensus that human activities are definitively causing global warming.

The language used to discuss climate change is dreary: replete with cliché, oversimplification and platitudes to cater to a supine audience. Another “once in a lifetime” or “once in a hundred years weather event,” where the “hundred years” suggests that a disaster is inevitable, organic, and the complete understatement of “weather event” also abnegating human liability for those catastrophes.

Local coverage of climate change is remiss if without discussion of the Black Summer bushfires, its impact on air quality in Sydney and its deterioration of biodiversity, but what of the sacred Indigenous sites destroyed in the fire? Coverage of the Adani coal mine protests is replete with references to Australia’s international climate obligations, and images of young Australians holding placards, but how much coverage has been given to the Wangan and Jagalingou people, whose traditional lands would be impacted by the mine?

Postcolonial fiction, arguably the most significant artistic movement in the past half century, uses literature as a tool to decentre eurocentric assumptions and give voice to the marginalised. Likewise, the artworks and literatures that have been created within the last decades, and which demand a place at the forefront of our readerly attention, have centred around environmentalist subject matters and fill gaps left by media coverage of climate change.

The mood of environmental decay has intruded into all aspects of contemporary letters, from fiction to philosophy and memoir. Take this excerpt from the opening of Martin Hägglund’s post-Kantian critique of secularity, This Life:

When I return to the same landscape every summer, part of what makes it so poignant is that I may never see it again. Moreover, I care for the preservation of the landscape because I am aware that even the duration of the natural environment is not guaranteed … Our time together is illuminated by the sense that it will not last forever and we need to take care of one another because our lives are fragile.

What makes Hägglund’s philosophy distinctly tied to its historical context is its emphasis on the environment as a precondition to self-understanding. It is difficult to understand oneself without there being an environment to contextualise that life, and it is more difficult to understand environmental decay in a world that lacks artistic continuity.

Even critical works of legal activism are remiss if omitting reference to the real issues posed by climate change. Finding the Heart of the Nation: The Journey of the Uluru Statement towards Voice, Treaty and Truth by Torres Strait Islander man Thomas Mayor documents the journey of the Uluru Statement, and calls for Indigenous Australians to have a greater role in decision making, especially in regards to issues such as climate change.

Works that feel the most alive, the most original and relevant, incorporate the issues of the environment into their substance. This is, after all, the measure of good art; the culture cultivates certain conditions that artists come to reflect in their works, a contextual influence without which their work would be bare entertainment. Their adaptation of culture, their interpretation of the history of a society, in turn contributes to and constitutes culture itself. This is the artistic framework that has been forgotten since high Modernism, but revitalised through environmentalist fiction.

Autumn, from Ali Smith’s Seasonal Quartet, is largely a meditation on Brexit, and an ode to a country on the brink of tearing itself apart. However, the motif of bees in the novel is a point of contrast from which we can reconsider national turmoil in the context of a threat facing the entire human population. Danial, an elderly art historian suffering from a terminal illness, obsesses over the plight of bees, ‘dying out, vanishing, collapsing, all over the word’ and evidently symbolic of the impact of human activity on the natural world.

Rarely does a new possibility open in the literary world that is not attached to the ideas or modes of previous artistic periods. Climate change is an issue sui generis, and a site for original art making removed from the oversaturated mediascape of the last century. Writing about climate change is a challenge: to think creatively about the scale of the crisis, but also to imagine new ways of understanding our relationship with the natural world, new avenues for driving social and political change.

We can understate the relationship between art and life itself, but it is undeniable that the two have informed one another since we developed language, and writing. We can choose the comforting paralysis that comes with facing such a monumental challenge. Or, we can write a new ending, a better ending, to this story.