Rarely in global history has a settler-society, forged from conflict and cultural erasure, been handed such a simple and painless potential first step towards justice. The chance to include a mechanism in the Constitution for a Voice to Parliament for First Nations peoples — as outlined in the 2017 Uluru Statement from the Heart — is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

As Australia gazes into the mirror of history, it sees itself in the positive achievements of its forebearers, but denies any culpability or undue benefit from acquiring its nationhood for free. John Howard reassured Australians that the crimes of rape and murder and dispossession and discrimination committed in its acquisition were done not by us but by “others”. However, this campaign of official denial is nothing more than a moral dead end; something else weighs on this nation’s heart.

Negation and silence have merely magnified the harm. Howard couldn’t bear to utter a simple apology to the Stolen Generations and victims of forced child removals. Peter Dutton walked out when Kevin Rudd delivered his apology.

The spirit of the Uluru Statement from the Heart provides an invitation to walk together on the path towards a reckoned-with Australia. Here, we might find an accountable and inclusive society which owns its history, so as to better imagine its future.

The Statement comprises three parts — Voice, Treaty and Truth. Self-evidently, the idea of Voice is concerned with the establishment of a constitutionally recognised Indigenous Voice to Parliament. The principles of Treaty and Truth, as the word makarrata suggests, are about coming together after a struggle. This is the simple invitation extended to all Australians within the Uluru Statement from the Heart.

However, Australia’s timid sentimentality and colonially-minded constitutional machinery hinders any progress. While there is goodwill in both the political and public arenas, many questions remain about the basic logic of the Voice. Why is it needed? Why must it be in the Constitution? Will it close the gap? Does it create a constitutionally enshrined race distinction where previously there was none? Aren’t the eleven First Nations representatives sitting in Parliament already the Voice of “their people”? And, of course, there are deeper and more complex questions of sovereignty, of self-determination, and of healing the scars that we carry as a nation.

As students, the Editors of Honi Soit support a “Yes” vote. However, we do not wish to reduce the scope of the Voice debate to simply a decision to vote “Yes” or “No”. While a “Yes” vote is an outcome which we support, it is our intention to interrogate Labor’s proposal and counter the unimaginative discourses taking place in the broader media landscape. The Voice is a first step in the change which is needed, but the form it takes — and what follows it — will be critical in paving the path forward.

The referendum, explained

What is a referendum?

The Constitution provides the basis for the powers and functions of Australia’s three branches of government — the parliament, the executive, and the judiciary. Unlike the ordinary legislative process, the Constitution can only be changed through the process of a national referendum.

Simply, a referendum is a vote in which all eligible voters are asked to respond to a question. The question will relate to a proposed constitutional amendment. For the proposed change to pass, there must be a double majority — meaning both a majority of all voters and a majority of states are required for a referendum to carry. The result then binds the Government to act based on what the voters decided.

Who can vote?

The vast majority of Australian citizens, aged over 18, can vote in this election. In fact, it is compulsory for them to do so.

However, the crucial misapprehension about the upcoming referendum is that it is a vote for all Australians. It is not. More than 32% of Indigenous people are aged under 18, rendering them ineligible to vote. Fifteen per cent of First Nations people over 18 are not registered voters. Those who are serving a custodial sentence of three years or more are also denied the right to vote in the upcoming referendum. Given that First Nations people are so uniquely disenfranchised by a carceral system which exists to perpetrate settler-colonial violence, it is bizarre to consider that this is used to preclude them from participating in a referendum predicated on the ideals of participation in democracy.

The fact that so much of the Indigenous population is rendered ineligible to vote on what will surely be the defining moment for Indigenous rights in the twenty-first century should be a call for us to do more to increase First Nations peoples’ access to the democratic process. We cannot assume the Voice alone will deliver this.

What is being asked in this referendum?

The Voice which Australians will be asked to vote on later this year poses a simple but monumental choice: whether or not the First People of this country should have input and play a role in shaping policies and laws being made about them.

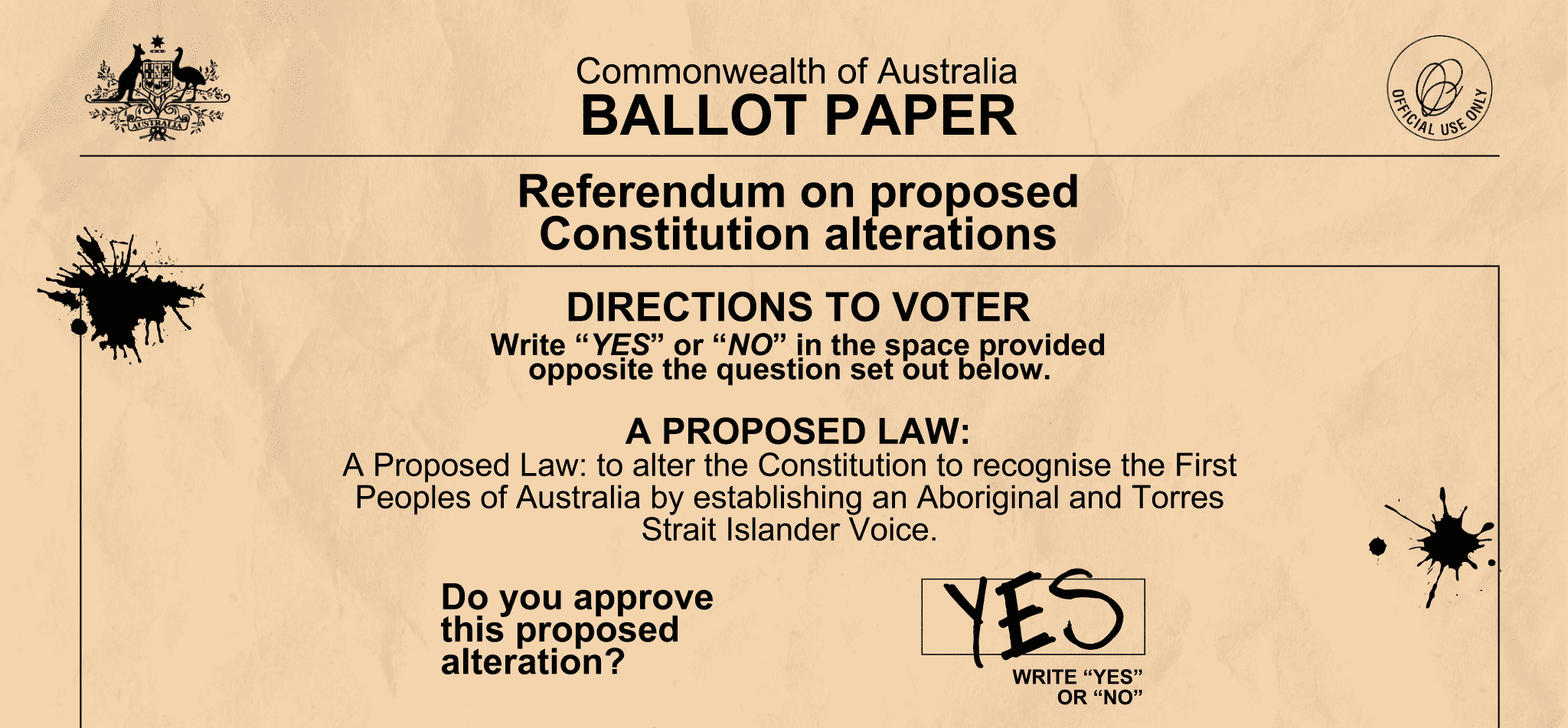

The government has proposed a referendum question, which is framed as:

A Proposed Law: to alter the Constitution to recognise the First Peoples of Australia by establishing an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice.

Do you approve this proposed alteration?

Eligible voters will be asked at the referendum to vote ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ to this question. The proposed alteration to the Constitution has been drafted as:

Chapter IX Recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples

129 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice

In recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the First Peoples of Australia:

1: There shall be a body, to be called the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice;

2: The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice may make representations to the Parliament and the Executive Government of the Commonwealth on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples;

3: The Parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws with respect to matters relating to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice, including its composition, functions, powers and procedures.

The referendum is expected to occur at the end of this year, sometime between September and December, with a result to be announced before the new year.

What is the Voice to Parliament, and how would it work?

As the first part of the Uluru Statement from the Heart’s three key components — Voice, Treaty, and Truth — the current Voice to Parliament proposal largely follows the vision set out by the community leaders who met in 2017.

The Voice would make representations to the parliament and the executive government on matters relating to the social, spiritual, and economic wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Whether or not the parliament would have the same obligation to adhere to the Voice’s advice is unclear, but its status as a constitutionally-enshrined body affords it a degree of authority.

The idea of a body that makes representations to Parliament is not unique to the Voice. As Constitutional Law expert Anne Twomey explained to Honi, individuals can make submissions and representations to Parliament. Twomey explains that “they’re unlikely to be influential as an individual unless they have some kind of particular expertise that the Government needs or wants to pay attention to.”

At this point, individuals often need collective organisation to develop a stronger influence. This can happen in various forms. For example, on a state and Commonwealth level, Australians are represented by an Ombudsman — who is tasked with handling complaints, and a variety of monitoring and review tasks across the public sector. The Ombudsman only has the power of persuasion, but can table reports requiring parliament to explain why their recommendations haven’t been enacted. Through the Voice, the representations that individual Indigenous Australians may seek to make would be given the strength of a collective as well as demonstrable expertise.

How will the Voice be structured?

The model set out by the Calma-Langton report provides for two members from each state, both territories, and the Torres Strait. A further five members are expected to represent remote areas due to their unique needs — one member each from the Northern Territory, Western Australia, Queensland, South Australia and New South Wales. An additional member would represent the significant population of Torres Strait Islander peoples living on mainland Australia.

Members of the Voice would serve four-year terms, with half the membership determined every two years. There would be a limit of two consecutive terms for each member. Two co-chairs would be selected by the membership of the Voice every two years. The national Voice would also feature two permanent advisory groups — one for youth and one for disabilities — and an ethics council to advise on the Voice’s values and governance.

That this model will be implemented is not certain, given Parliament’s discretion in determining the makeup of the Voice. But it provides a good guide for what the Voice will finally look like.

Why we support the Voice

The Voice is needed because this country was taken by force. White Australia was forged by colonial might, Indigenous lands and waters were never ceded, and compensation was never paid. The doctrine of terra nullius promoted the convenient fiction of an empty Australia. The dehumanising intent of this claim was, and continues to be, reflected in law and policy ever since. Creating a Voice to Parliament recognises First Nations peoples’ presence and establishes a unique system of influence on policies directly pertaining to them.

The voice and self-determination

At the outset, it should be made clear that approximately 80% of First Nations people support the Voice based on recent polls. We make this observation because it is impossible for the colony to truly move forward with First Nations justice without listening to the voices of First Nations people. The Voice is the culmination of consultation and debate within First Nations communities. This fact goes a long way to why we support a “Yes” vote.

Beyond this, Indigenous peoples have an inalienable right to self-determination. It is important that First Nations people have the capacity to exercise self determination by making decisions that impact and shape their lives.

The Voice does not fully implement self-determination. Self-determination also includes the right to have autonomously run institutions which have the power to make decisions relating to their communities. The right to self-determination would also give Indigenous peoples veto power over decisions which negatively affect them, including over the exploitation of their lands. Nevertheless, the Voice would mean First Nations peoples are consulted on decisions which affect them, albeit little else.

Why the Voice will improve conditions for grassroots Indigenous communities

The sport of Indigenous affairs has always been played at a much higher level than Indigenous people have ever been allowed to occupy. The Voice changes this through the validating gestures of contrition, truth-telling, and dialogue.

Annual Closing the Gap reports continue to show Indigenous people measure far behind other Australians on many fronts; political representation of Indigenous people is stagnating. Thirteen years on from the release of the Closing the Gap report, none of the targets are progressing — we need an imaginative solution to Indigenous self-determination that will stick.

The Voice looks to the future. Right now, progress is extremely limited and the gap is closing far too slowly. The life expectancy disparity between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people across Australia is still unacceptably high. Aboriginal community-controlled health services have been critical in closing the gap — an example of what can be achieved when Indigenous Voices are heard. So much more could be done if that right to be heard was forever enshrined in the founding document of this country.

By making recommendations to both the legislature and the executive, the Voice will have the ability to influence laws and policies before they are ratified, rather than challenging existing legislation in the courts.

Currently, First Nations people can only challenge legislation through litigation — a status quo which has continually failed Indigenous people, as progress can only be won in the courts by non-Indigenous lawyers. There is no mechanism for the vast majority of Indigenous people to challenge the government. They are always reacting to government decisions, rather than influencing them.

The Voice, as a political tool, will compel consultation between the parliament and the executive government and Indigenous people. This will allow for more meaningful and structural engagement with First Nations voices in the design and implementation of policy. If the Voice is approached in good faith, Honi believes that this will lead to better policies. In a less ideal world, the Voice will deny politicians the ability to feign ignorance. Decision-makers will be held accountable as recommendations are made public, thus demonstrating the incongruence of their policies with the wishes of First Nations people.

Why the Voice should be enshrined in the Constitution

Honi spoke with Gunaikurnai Wotjobaluk writer Ben Abbatangelo, who expressed misgivings about the perceived “bulletproof truth” that constitutional enshrinement will safeguard the Voice against neglect or inefficacy.

“The theory of constitutionally enshrining the Voice is that it can’t be abolished or ignored. I don’t think that’s necessarily a bulletproof truth, though. You can create the Voice and enshrine it, but there’s no real guarantee that Parliament won’t reform the model of the Voice.”

Abbatangelo stresses that the Voice “relies on the government acting in good faith — something which they have never been able to do. Every time we come to drink from the well under false winds of change, we are drowned.”

This fear lives in the memories of First Nations communities — that each time Indigenous people are lured into the light, they are mugged by the darkness of this country’s history. The scars of colonial betrayal are worn on the backs of Indigenous people, and communities are naturally hesitant to write the government a blank cheque for their constitutional rights.

However, constitutional law expert Elisa Arcioni claims that the debate about detail is a disingenuous one.

“The Constitution should never contain all of the detail about every institution. The design of the Constitution is to set up the basic framework of an institution and its key role. All of the detail is then to be determined by parliament through legislation.

“But because there are legitimate questions about the detail, that has been weaponised by ‘No’ proponents as a way to sow confusion and concern.”

Constitutional enshrinement retrospectively recognises that even in the tolerant and multicultural nation Australia purports to be, the pre-existing human rights of its original inhabitants are inalienable and unique. This should have been reflected in the nation’s founding document.

To deny that now, given this chance, would constitute an outrageous validation of British dispossession, the injustice it sanctioned and the cultural genocide it licenced.

The risks of a failed referendum

First Nations people have been building towards constitutional recognition since the 1950s, and an immense amount of political capital has been invested into this process. If it were to fail, the political will to pursue Indigenous justice would dissipate. A “No” outcome, resulting from the racist campaigns by the Liberal and National parties — as much as a “progressive ‘No’ campaign” — does not represent a rejection of the political system which upholds Indigenous dispossession and is, instead, an emphatic legitimisation of this system.

There is little prospect that a “No” vote would provide an impetus for a move towards Treaty and Truth. Instead, it would deter any government from pursuing meaningful steps towards justice for First Nations communities. This process was played out with the 1999 republic referendum and it will play out again.

A “Yes” vote is the only way to reject the racism of the right-wing “No” campaign. It is the only way — given the referendum has already been announced, and will occur — that momentum towards greater goals can be created. It is largely for this reason that a “progressive ‘No’” position should be rejected by left-wing students.

Why Honi?

As to the specific question of “why Honi?” — the act of making a radical case for the Voice is an integral part of our historical contribution to the struggle for civil and political rights. It is Honi’s opposition to the Vietnam War, its support for queer and women’s liberation, its ongoing critique of Invasion Day which come to mind in this history.

The referendum facing us now is different to these issues. The Voice has been proposed by the government and has received support from broad swathes of the political and corporate establishment. Yet, it is nonetheless incumbent on Honi, and all left-wing students, to support the Voice because it is fundamentally right to do so. Australian citizens must vote in this referendum. A “Yes” vote will provide a foundation upon which the radical work towards true First Nations justice can begin.

The case against the Voice

The campaign against the Voice has been driven by a racist preoccupation with denying First Nations people a presence in Australian society and the Constitution. This is the reason for which the Liberals and Nationals have never expressed support for the Voice proposal.

Does the Voice create inequality in an otherwise race-blind Constitution?

The Constitution which established Australia was already racially selective by expressly ignoring the existing custodianship of Indigenous peoples before European invasion. Its architects went to great lengths to assuage the guilt and discomfort of Australia’s fledgling colonies, yet said nothing of millennia of prior ownership.

The Constitution must be seen as an instrument of colonial rule, and its silence on Indigenous ownership was deliberate — an explicit act of legal and cultural deletion. Race was assumed to be white European and thus not explicit. Black Australia was dealt with by exclusion.

As such, the recognition of First Nations peoples — and the enshrinement of a Voice to Parliament — in the Constitution is a means by which the colonial logic of the Constitution, and its institutionalised disavowal of the existence of First Nations people can be partially remedied.

The Voice will afford First Nations people no additional “rights” compared to non-Indigenous people. This is not a positive. To herald the Voice’s lack of binding power is to acquiesce to the violent settler state, the system which stole these powers from First Nations people in the first place. Honi rejects this.

The Constitution should give First Nations people the powers to control, not just provide input into, decisions which affect them. Those rights are inherent within First Nations’ people’s historic and ongoing claim to sovereignty. It is greatly regrettable that the Voice doesn’t do this.

Will the Voice impact Indigenous sovereignty?

Among the most contested myths about the Voice is the question of sovereignty, and the claim that the Voice would force Indigenous people to surrender their sovereignty.

To challenge the claim that any constitutionally-enshrined Voice would extinguish First Nations sovereignty, it is crucial to first understand what sovereignty is.

As constitutional law expert Professor Anne Twomey explained to Honi, “sovereignty means different things to different people. For many Indigenous people, sovereignty is as much a moral or political concept as it is a legal one.”

Under international law, sovereignty refers to a sovereign state — one which has clearly defined borders and a permanent population, and one which exercises control over issues of law, immigration and trade.

It is generally accepted that sovereignty, in the legal sense, can be acquired either through cession, conquest or prescription of land deemed terra nullius. Although it is true that First Nations people never surrendered collective sovereignty over their land, there exists no legal framework for Indigenous people to exercise sovereignty in real terms.

Then, there is the more abstract, intangible definition of sovereignty — the right of Indigenous people to practise culture and exercise a spiritual relationship with their traditional lands and waters.

In a contemporary settler-colony such as Australia, First Nations people can only exercise a diluted version of sovereignty in the narrow political sense. In real terms, a constitutionally-enshrined Voice has the potential to enable greater exercise of sovereignty.

The Uluru Statement clearly stipulates that Indigenous sovereignty shall coexist with that of the Crown, and neither can be extinguished by a constitutional amendment.

It says: “Our Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander tribes were the first sovereign Nations of the Australian continent and its adjacent islands, and possessed it under our own laws and customs …

“This sovereignty is a spiritual notion: the ancestral tie between the land, or ‘mother nature’, and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who were born therefrom, remain attached thereto, and must one day return thither to be united with our ancestors. This link is the basis of the ownership of the soil, or better, of sovereignty. It has never been ceded or extinguished, and co-exists with the sovereignty of the Crown.”

All of this is to say that a constitutionally-enshrined Voice to Parliament has no legal power to impact sovereignty as it currently exists. This can only be done through a framework of very specific provisions during the Treaty process, and so it is a fallacy to claim that the Voice to Parliament would force Indigenous people to surrender sovereignty to the Crown.

What sort of Voice do we want?

Labor’s proposal is intentionally modest — it offers only constitutional recognition, but does not bind the parliament to take the recommendations of the Voice. This should be contrasted with the rights afforded to Indigenous peoples under International Law, with veto powers and autonomous institutions par for the course. The fact that the Voice has deliberately been constructed by the government to withhold these rights from Indigenous people should be vehemently condemned. The government has calculated that, to convince white Australians of the Voice’s worth, it must be curated to not pose too much of a threat to the status quo. The State doesn’t want to relinquish its powers over First Nations people. Accordingly, the Voice does not do the required work to destabilise settler control. Honi wants a Voice that implements the wishes of First Nations people, that gives true control over their lands and waters. We should not settle for less.

Why Voice first? What about Treaty and Truth?

Principally, the idea of constitutional recognition and an enshrined Voice to Parliament is not one which is revolutionary, or even particularly new. Questions of whether Indigenous people should be included in Australia’s founding document have been asked since the time of Charles Perkins and the Freedom Rides.

The question which must then be asked is why a Voice must come before either of the remaining two components of the Uluru Statement. The Labor government is evidently following the order set out in the Statement chronologically, despite claims from key groups in political and activist circles — particularly the “progressive ‘No’ campaign” — that a negotiated Treaty should be the government’s priority. To lend credibility to these claims, as the only Commonwealth nation without a Treaty with its First Nations people, it is critical that this chasmic omission is redressed. However, enshrining a Voice before embarking on a Treaty-making process will undoubtedly afford Indigenous communities more political capital to invest in a Treaty.

Wiradjuri woman and member of Uluru Youth Dialogues Brydie Zorz told Honi about the significance of achieving an established Voice before negotiating a Treaty.

“Having a Voice which is constitutionally enshrined will give First Nations people the political power we need to then embark on a Treaty process.”

The other advantage of the Voice preceding Treaty and Truth is that it means there will be an established, and influential body to represent First Nations voices during the Treaty-negotiating and Truth-telling processes. As it stands, First Nations institutions are highly decentralised, and are run in greatly varying ways, usually dependent on regional differences. Many are underfunded and defunct. A national Voice will be able to bring these regional voices into a single forum, mitigating the issues of resources or factionalism facing some of these groups. This will make negotiating with the State a less onerous process, leading to faster progress towards Treaty and Truth and better outcomes in both respects. Moreover, as the Voice consolidates influence and becomes a normalised feature of government, so too does its authority, improving the political power of First Nations voices.

What happens after the referendum?

Speaking with Honi, Wiradjuri Gamilaraay author and journalist Stan Grant expressed less worry about the referendum itself than the day after Australians cast their vote.

“Irrespective of whether people vote ‘Yes’ or ‘No’, we’re going to wake up in a nation still so deeply wounded,” Grant observes.

“We are all deeply wounded and we are all implicated and complicit in this moment in different ways. But we’re going to wake up and we’re going to be in the same place — in this scarred and broken land asking who we are and asking where we are.”

However, the day after Australians vote on a Voice to Parliament will be a markedly more painful day in the event of a failed referendum. Of course, negative narratives will continue to frame discussions of Indigenous justice, but there will be a new sense of contempt — one which is nationally-sanctioned and newly resuscitated by an empowered right-wing.

Business-as-usual will continue to produce egregious policy failures that will waste money and cost lives. Australia’s pathetic tradition of low expectations will have triumphed again.

How will we recover from a “No” vote? How will we come back as a nation? The distrust and alienation of First Nations people will grow, any remnant faith in reforming and improving settler systems will wither. Indigenous people will continue to be viewed as a problem to overcome, rather than as a people offering ideas and solutions grounded in their deep sense of culture and care for Country and their intimate knowledge of people and society.

It will be a day where First Nations people will feel, perhaps more than ever before, invalidated and judged to be of no consequence to a country they have called home for thousands of generations. How can we explain this to our children and grandchildren? How will we explain it to ourselves?