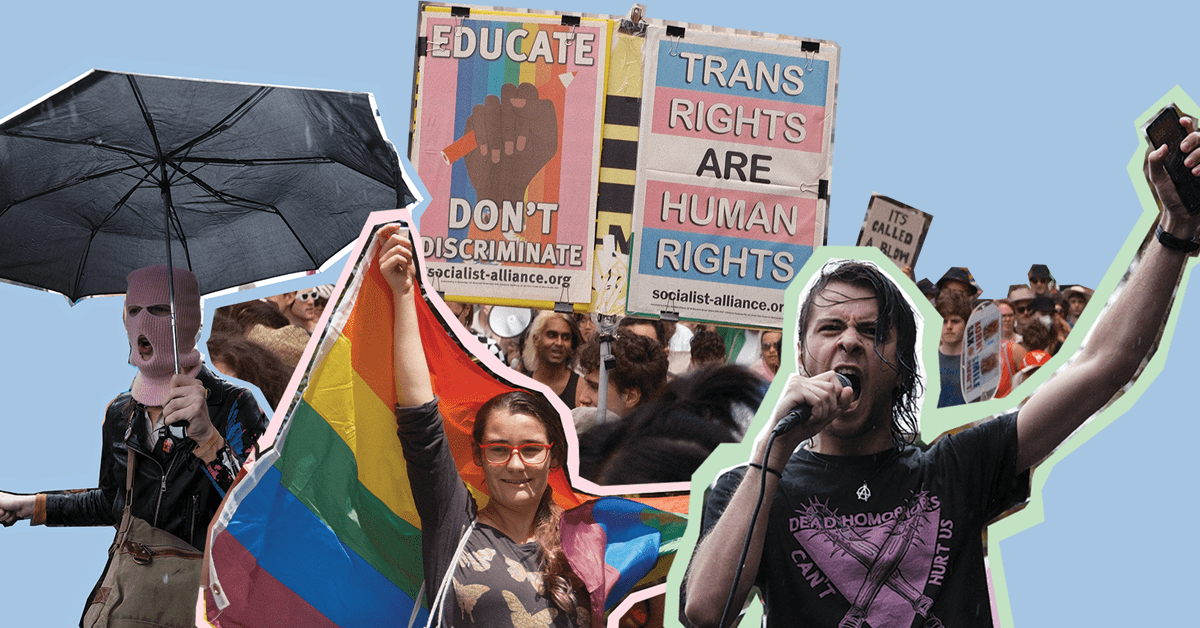

Queerness is vibrant and colourful. Our days of resistance, where we organise in solidarity against queerphobia, are as vibrant as the safe spaces we form and our days of celebration. Whether it’s a Trans Day of Visibility (TDOV) march or Sydney Mardi Gras, identifiable moments of queer expression are celebratory.

This positivity and enjoyment we get in the expression of our identity is necessary to how we interact in society, but it is also equally evident in how queer identity has become commodified. As a historically marginalised and stigmatised identity, corporations profit from our nominal inclusion in heteronormative society.

Corporations, police forces and governments can conveniently forget our very real oppression by incorporating the most profitable elements of queer celebration.

This commodification comes with the implication that the Queer history of struggle — which provides lessons for future organising — has become dissolved of its radical elements to be suitable for the market and state.

To understand this we only need to go back to the first Mardi Gras march in Australia on the 24th of June 1978 on Oxford St. A peaceful march, with radical calls for the decriminalisation of homosexuality and to give queer people industrial protections, became a riot. 53 people were arrested and faced intense police brutality.

The pro-business flagship, The Sydney Morning Herald, published the names and occupations of those arrested, effectively outing them, leading to disownment and loss of livelihoods.

Unlike yesteryear, Mardi Gras is now represented in an era of apparent consensus between the state and queer people. The corporate Mardi Gras board allows the NSW Police to hold a float, like they did in the 2023 march, that read, “NSW Police: Glowing with pride.” Police are the weaponised arm of the capitalist state —they break strikes and criminalise queer groups. Their representation at the march is not the bells of progress a-ringing, but a crude paint job to hide the reality of the police as the repressive, armed wing of capital.

The board embraces sponsors like Coles, which claims that “everybody is welcome at [their] table”. Does this include 7,500 workers whose wages the company stole to the tune of 115 million dollars?

Pinkwashing by corporations seeks to separate history from reality, using the promotion of LGBT rights as evidence that society includes queer people. It leads to historical amnesia, where memories of state and police violence are lost, because now they have a shiny, progressive facade.

The market facilitates the conception that the police and queer community are brothers in arms. We are now a queer “market demographic” for brands, inculcating the community with the germs of capitalism: you are an atomised, queer individual that has the freedom to buy products in rainbow.

As this history is abstracted, so is the story of how queer solidarity and community broke the back of systemic oppression.

Back in 1978, marches in solidarity with those imprisoned after the events of the 24th were organised for the 15th of July. These were organised by elements of the labour movement and socialists, who rallied thousands of protestors outside of police stations all over Sydney, pressuring them to drop criminal charges. Many eventually did, albeit quietly.

In these moments of organisation, Mick Armstrong, a founding member of Socialist Alternative and key political organiser in the 70s, remembers the years of 1978-9 as the “most impressive campaign for LGBTI rights ever seen in this country [that] paved the way for many future victories.”

This organisation saw considerable efforts nationwide and found success in NSW. This movement saw the repeal of laws that gave police powers to control queer behaviour in public in 1979, as well as amendments to the Anti-Discrimination Act which was amended to include protection based on sexual orientations in workplaces in 1982.

Significantly, these movements in solidarity with groups against apartheid in South Africa, formed the right to strike in the state.

This scale of mass organisation no longer exists, and the market has facilitated a perception that it is no longer necessary. The imperative that organisation is not needed is a larger reflection of how any avenue of queer struggle is constrained into parliamentary reform. All the protections we enjoy, however, have never been handed to us through reform, but through struggle.

Queer liberation needs to be revitalised through solidarity with other exploited and oppressed groups. When we focus our struggle on the fight for the exploited against the exploiter, we build mass movements that aid in the process of liberation.

I already see the germs of this within activist spaces such as Pride in Protest (PiP), a grassroot queer collective which organises with various other movements like the Blak rights movement to fight police brutality. Why do we let the police, who perpetuate violence and marginalisation of queer and Aboriginal people (at highly disproportionate rates, no less), march with us?

Lidia Thorpe’s words before her participation in the 2023 Sydney Mardi Gras with PiP got to the heart of the need for intersectional mass struggle.

“Rights in this country for over 200 years have been denied, not only for first peoples…[but] for people who choose to love who the fuck they want to love. And if a trans man say that they’re a man, well that’s my fucking brother!”

Her words illuminated that solidarity amongst Blak and queer struggle which could revitalise the mass movement potential for both groups. Their shared experience of repression is important, in that they have the shared tools to bring about their liberation. This could materialise itself in the organisation of a mass movement by both groups rallying against police violence to dissolve it. We are attacking an issue of shared relevance for our own liberation.

Whether it’s the soft totalitarian processes of the state that seek to govern the radicalism of sections of Indigenous struggle through the Voice referendum, or the growth of the far-right and its attacks on the queer movement, we must cooperate to fight for a better world.