“When I am shaving in the morning, I am not thinking about Australian foreign policy.” That was the response of Henry Kissinger, who served as American National Security Advisor and Secretary of State from 1969 until 1977, when asked about the direction of Australian foreign policy at a Sydney press conference. His casually dismissive attitude towards an American ally is a testament to his worldview: that geopolitics and history should be understood as a balancing of great power interests at the expense of human lives. While that may have made him an expert in statecraft, his underestimation of mass politics would lead to his political and moral downfall.

Kissinger lays out his worldview in his 1957 book The World Restored, where he idealises Austrian statesman Metternich and his reactionary restoration of European monarchies after Napoleon’s 1815 defeat. The true objective of diplomacy, he argues, is to establish and maintain order as opposed to improving social outcomes. Turn of the 19th century attempts in France to create democracy and end feudalism were, in his view, destabilising. Therefore, war (and by extension war crimes), become a mere tool to create that stability. His complicity in Pinochet’s Chilean dictatorship, encouragement of genocide in East Timor, and most infamously his decision to carpet bomb parts of Vietnam and Cambodia while deliberately delaying peace talks, only make sense when the world is a colourful map with changing borders rather than a collection of human beings. Neoliberals who praise him for China’s opening or US-Soviet detente misunderstand his reasoning. He never cared about the prosperity of either nation until he felt the world would be made more ‘stable’ with de-escalation. When you treat the world like a game of chess sometimes you will make good moves with bad intentions.

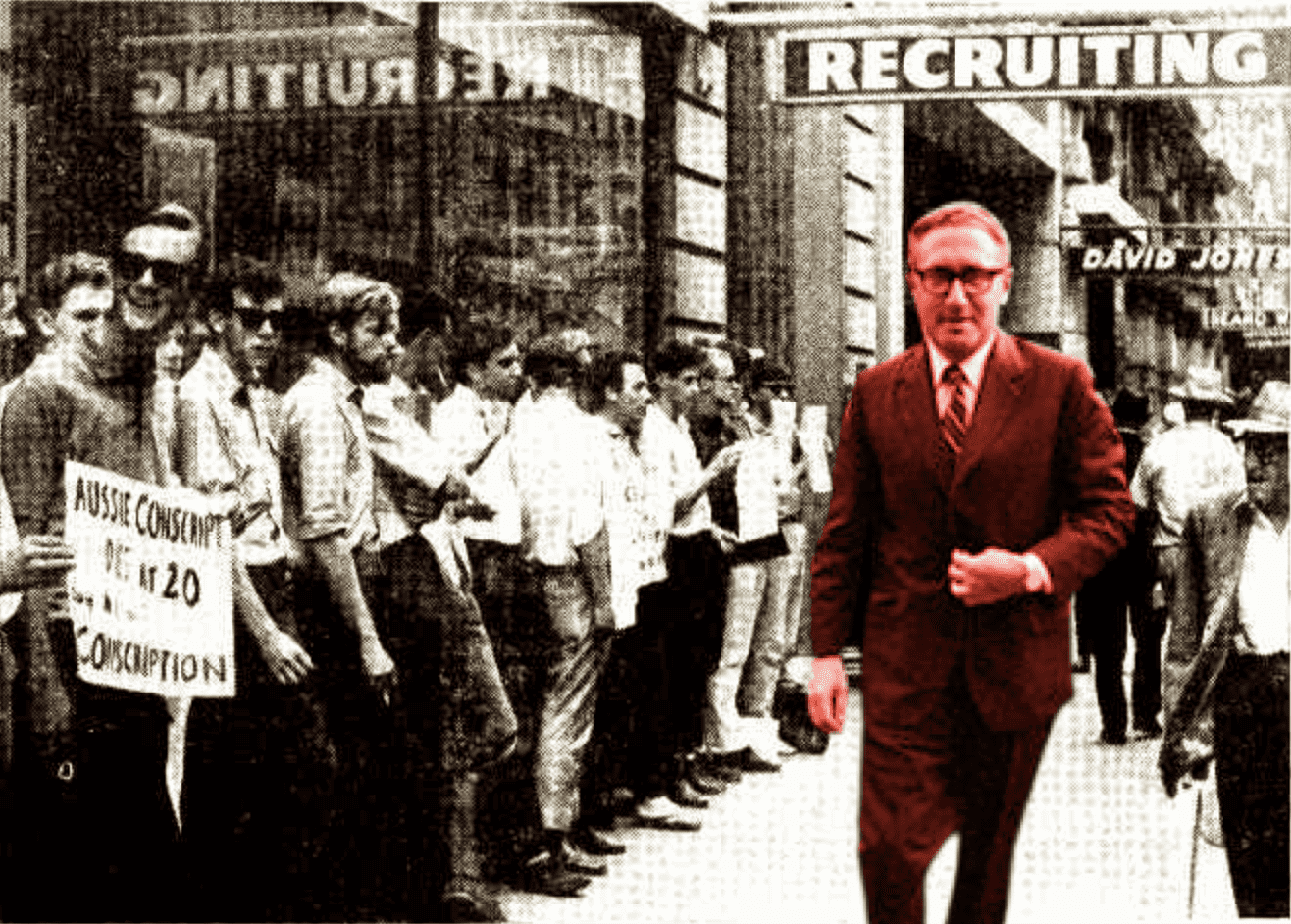

Kissinger’s disastrous Vietnam policy can be thanked for one thing: creating an Australia that stood on its own for the first time since Federation. Former foreign minister Gareth Evens argued that the expression ‘Australian foreign policy’ was almost a contradiction in terms during the early Cold War period. Whitlam’s election in 1972 changed that. After the ruthless Christmas Bombings of North Vietnam in December 1972, the Prime Minister sent a letter to Nixon and Kissinger calling for an immediate reversal in US policy. His treasurer Dr Jim Cairns went further, publicly calling Vietnam the “war of the great lie.” The Labor government also quickly repealed a Menzies era conscription law which had sent over 60,000 Australians to fight for America’s crusade against communism. Kissinger was characteristically dismissive of Australia, threatening to “freeze [Whitlam] for a few months” until he “got the message.” Luckily, the Whitlam government did not back down and the Vietnam War, even in mainstream circles, is remembered as a failed imperialist project.

Anger in Australia at Vietnam and America in general was not inevitable even among university students. A September 1966 poll in Honi showed that 68% of students supported Australia sending troops to Vietnam. Left-wing activism, often led by students, was a large reason why Labor and Australia as a whole turned against the war. Massive protests against conscription, which peaked at 200,000 strong nationally, were birthed on university campuses. On our very own Quadrangle lawns on May 1, 1969, hundreds of students and staff gathered to protest NSW Governor Sir Roden Cutler’s inspection of the Sydney University Regiment. Protesters threw tomatoes, some reportedly hitting senior staff such as the Vice Regal. After Whitlam ended conscription in 1972, one student joked to Honi that it was a “worthwhile tomato.”

Kissinger was equally contemptuous of student activism. The CIA commissioned a report called “Restless Youth” in January 1969 “for a study of worldwide student dissonance,” finding that student protests posed a significant threat to their Vietnam narrative. Kissinger disagreed, allegedly arguing, “they care so much because the stakes are so small.” He could not have been more wrong. As Australian historian Paul Ham put it, “like hundreds of little tugboats, the political misjudgements, draft resisters, death notices, and protesters nudged Australian and American minds on a new bearing.” Kissinger’s inability to understand the potential of mass politics was a massive miscalculation and one modern politicians should learn from.

While the protestors on the Quadrangle won the battle, Kissinger and his worldview won the war. Even just looking at Australian politics, it’s hard to see Albanese ever standing up to Biden like Whitlam stood up to Nixon. From maintaining the AUKUS deal to silence on Palestine, the current Labor government is making the same cynical, heartless choices that Kissinger would have. In an effort to preserve global order and alliances, they are ignoring injustices impossible to conceptualise. Whitlam set up a Palestinian Liberation Organization liaison office in Canberra and publicly condemned Zionism, whereas Albanese took weeks to publicly call for a ceasefire.

Christopher Hitchens dedicates his 2001 book, The Trial of Henry Kissinger, to “the brave victims of Henry Kissinger.” This article too is dedicated to the millions of lives Kissinger destroyed, and the hope that again Australia will stand on its own and for a worldview that looks beyond stability.