From Pompeiian electoral propaganda inscribed in walls and tablets, to Benjamin Franklin’s ‘join or die’ proto-poster, to Toulouse-Lautrec’s first lithographic Moulin Rouge, to the contemporary ‘keep calm and […]’, the artform of postering is an unmistakable signifier in anthropology.

The paper poster supposedly dates back to the late 15th century with William Caxton — an Englishman who introduced the printing press in Brugge — which included the first advertisement poster listing the benefits of thermal waters in 1477. However, it wasn’t until the birth of lithographics and the flourishing 1880s French art scene when a leap in postering occurred as an accessible medium of communication.

Lithography can be defined as the process of printing a graphic or signifier on a flat surface — the modern poster. The poster is a medium of visual communication which transmits graphic images and textual signifiers, forming a historic, universal and expansive language. Parameters of postering include vantage sites, timing of mounting, and of course, the messaging. University culture, in particular, has adopted the form of postering to communicate with fellow students.

Fast forward to the grey pavements of Eastern Avenue: postering and flyer handouts have become synonymous with the student experience at the University of Sydney. Students on campus have been constantly pasting the walls and halls with posters descending from the likes of fanatical student politicians, eager University of Sydney Union (USU) clubs, self-proclaimed anarchists and hopeful revue promoters since the university’s inception in 1850.

The Tin Sheds gallery, USyd’s contemporary exhibition space for the School of Architecture, Design and Planning, has historically been the archive for USyd’s poster evolution. Now the University of Sydney largely manages the poster archives but it still holds a mirror to the tropes and social structures that permeated student culture at the time of circulation.

Posters have historically served as a valuable messaging format for student safety reports and activist updates. For example, Tin Sheds houses posters of student activist media such as “SEXUALLY HARASSED?”: USyd’s Sexual Harassment Committee poster by Jean Clarkson (1984).

Similarly, community cultivation and union-building efforts amplified their work through posters. This evidenced in “ARTWORKERS” general meeting from the Lucifoil Poster Collective poster advertising the 1981 Artworkers Union Annual General Meeting by Leonie Lane.

Student politicians and student groups have always built community and momentum through posters. Back in the day, snarky sub-tweets or Facebook comment essays took the form of papering over other faction posters and strategically combating each other’s slogans. Now collectives use posters to build interest in rallies, speak-outs, collective events and protests, as well as advertise their group’s ethos.

Mostly gone are the days of political persecution with postering wars. Harrison Brennan, the 2024 SRC President, tuned in to discuss the changing role of postering around campus. Today, when students arrive on their first day of university, they are met with an overstimulating barrage of rally promotions, ambiguous socialism conferences and student collective call-outs layered over City Road Bridge and coating the boards of Eastern Avenue.

Leading the conversation with an evaluation of current postering efforts, Brennan confessed the student practice “is in no healthy state,” mentioning that “the clubs and societies posters can feel a little bland.”

Despite this, Brennan acknowledged that despite the fact postering has “died for many, it is not dead yet” noting that its function is “building community engagement” that surpasses the contentious borders of student politics or stagnant club gatherings. The practice and design has been increasingly informed by the 70s-90s epoch with archival inspirations, parodies of past slogans and bold collage art leading the trends. When referencing postering in contemporary student politics, Brennan said “our posters are always antithetical to management.”

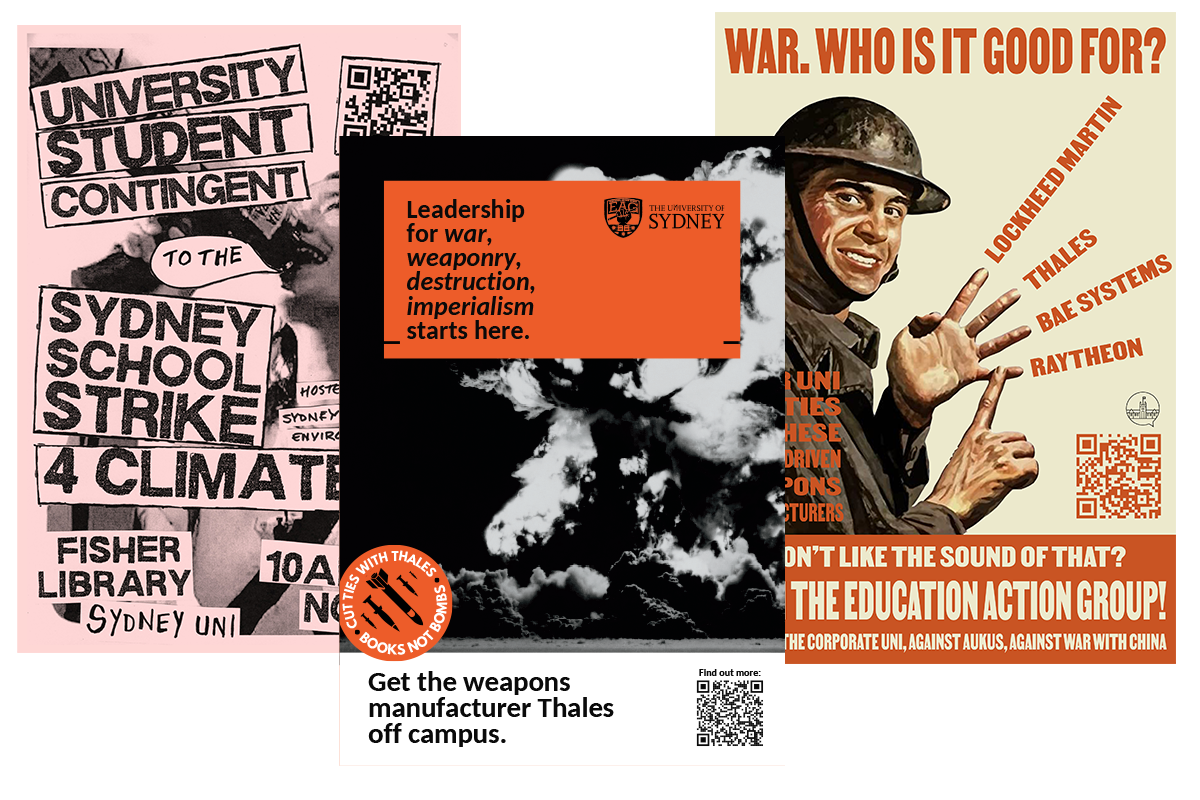

Today, posters around campus are used to promote rallies, entice audiences to attend revues and advertise campus happenings. Ishbel Dunsmore has been a recent voice in poster design who has leant in to the parody of USyd management copy. Dunsmore’s posters play on war propaganda and appropriate USyd management’s advertising material to promote student activist initiatives. Brennan said “posters used to litter the entire campus” but noted the only remnants of poster chronicles are the “Trotsky group battles” on the Taste Baguette notice board in the Law Annex.

Now posters must only be mounted on designated poster boards, or they risk removal by USyd management. Common poster boards are found at Eastern Avenue stands, Taste Baguette, the walls of the Education Building or behind the toilet cubicle doors of Fisher Library. Brennan said that despite the designation of spots, he has noticed that “Palestine posters [are] being taken down by the conservative clubs and campus security guards” from bus stops and Eastern Avenue boards.

A spokesperson for USyd referred Honi to their existing ‘Advertising on Campus’ policy, and told Honi that “we don’t remove posters from our designated spots on campus unless we consider them in breach of our policies, charter or codes of conduct; we respect this as a form of free speech and take action against wilful attempts to damage or remove posters if it is done to inhibit another person’s right to free speech.”

In recent times, USyd management has been more decisive with their implementation of policy: “we also have noticeboards reserved for official University notices. We remove non-University notices from these boards, so that our information for students is able to be easily accessed.”

Regardless, postering has taken on new formats with the advent of the Information Age and emerging social media battlegrounds. Even though the era of ‘sensational poster drops’ has been stowed in the attic, stylised infographics and visual call-outs now fill our Instagram stories instead of our poster boards.

There is no question that contemporary poster-making pulls from and appropriates the past to successfully convey messages to our student populace today. Both in its generation, output and consumption, postering is a communal activity and backbone of campus communications. So despite speculation that postering may be “stale” or “dead” the spirit of postering is alive and fighting to be well. Instead it is manifesting in different mediums, paying homage to its iconic, lithographic history whilst looking to the future of visual communication.