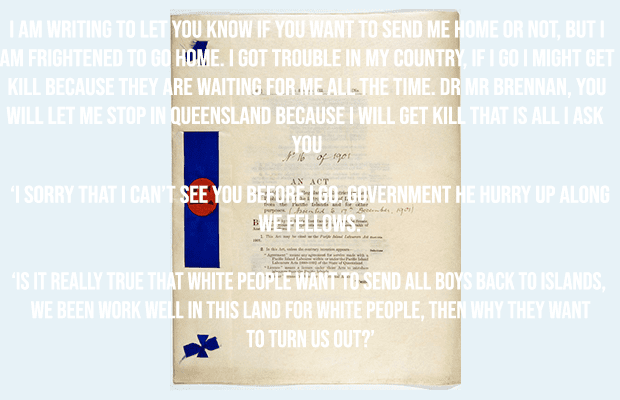

‘Dear Mr Brennan,

I am writing to let you know if you want to send me home or not, but I am frightened to go home. I got trouble in my country, if I go I might get kill because they are waiting for me all the time. Dr Mr Brennan, you will let me stop in Queensland because I will get kill that is all I ask you.’

– Letter from Peter Janky of Malaita, Solomon Islands to John Brennan, Queensland Immigration Department.

Dozens of letters like this were sent to the Queensland Department of Immigration near the end of 1906. They give an insight into the emotional trauma and uncertainty generated by the Pacific Island Labourers Act (1901). After 31 December 1906, all South Sea Islanders resident in Australia were to be forcibly and permanently deported to their countries of origin, with the exception of those born in Australia or those who had been residents continuously since before 1879. Between January 1907 and December 1908, between 4500 to 5000 Islanders boarded steamships bound for the South Sea Islands. It remains the largest mass deportation in Australian history. This article tells the story of how these fateful events came about.

**********************************************************

‘I sorry that I can’t see you before I go. Government he hurry up along we fellows.’

– Louis, a Malaitan Islander to his girlfriend (1906)

From the late 1860s to the early 1900s, the Queensland sugar and cotton industries had become structurally reliant on cheap labour from the South Sea Islands. During this time, approximately 67,000 Islanders were brought to Australia to work on vast, isolated sugar plantations. Yet in spite of the significant economic benefits that the labour trade brought to the state, or more specifically, to its burgeoning plantation class, resentment against Islanders proved widespread.

Although many Islanders—referred to as ‘first indentures’—completed their contracts and returned home, others chose to stay on in Queensland, seeking further employment on plantations or in other industries. Most Islanders who chose to remain in Australia believed that after their initial term of employment, they would be able to demand better wages as higher skilled workers. Many had formed close associations with their local communities, intermarried, and were members of educational institutions and churches in their adopted homeland. Additionally, returning home carried a number of risks. The extractive process of colonisation in the South Pacific meant that living conditions on the islands had deteriorated, whilst those who had been absent for long periods often found it difficult to readjust to life on return, particularly where family members had departed or were deceased. Dire circumstances had also seen the outbreak of high levels of violence, particularly in the Solomon Islands from where the majority of indentured workers were drawn from the 1890s onwards. Yet for those Islanders who chose to make Queensland home, life was not without risk either.

From the moment indentured workers arrived in Australia from the South Sea Islands, racially motivated campaigns sought to regulate, surveil and segregate them. Public narratives on Islanders shifted between viewing labourers as naïve, docile ‘children’, and dangerous, impulsive criminals. In an interview for the 1869 Select Committee in Queensland Pacific Island Labour, Mr Charles Eden, a planter from Cardwell district, called his workers ‘docile, laborious, good-tempered and affectionate’, but moments later referred to them as capable of ‘acting like warriors, dancing and howling like madmen… jumping and shrieking in the most appalling way.’ Public organisations opposing Pacific Islander labour sprang up throughout the country. One group, founded in Brisbane in 1871, stated their determination to ‘stop the deleterious effects on the civil, religious, and political institutions of Queensland’ brought by a ‘class of unintelligent labour of the semi-civilised races.’

By the 1880s, state legislation mandating the surveillance and restriction of South Sea Islander populations intensified. Under pressure from white trade unionists, the Queensland Pacific Island Labourers Act (1880) confined Islanders to work only in industries related to ‘tropical or semi-tropical agriculture.’ This allowed Islanders to continue to work on cane farms and in businesses tied to the plantation economy (general stores, boarding houses, transportation), but not in other economic spheres. In this period, the vitriol directed towards the resident Islander population became more intense and achieved particular prominence in the discourse of early Australian nationalists and trade unionists. The famed Australian federationist, Harold Finch-Hatton wrote in his 1885 travelogue Advance Australia! that in Northern Queensland ‘intercourse with civilisation is producing its usual result among uneducated savages and the kanakas in Mackay are starting to get troublesome.’

E. J. Brady, poet and editor of the Labor Party newspaper The Australian Workman, gave an account of his visit to ‘Kanakatown’ in Bundaberg in the 1890s that now serves as a testament to racist attitudes prevalent in the period. ‘The Kanaka quarter was an edification, a labyrinth of rookeries on the outskirts of Bundaberg, where black and yellow make their lairs. It remains to me as a nightmare of evil sights and smells and sounds…Tommy Tanna [a stereotypical name attributed to South Sea Islanders] was in a bad humour. Race-hatred gleaned in his bloodshot eyes. Murder stalked upon the hot, quiet Northern night. It was an evening stroll through a village of darkest Papua, where dusky gloom was balefully lighted by a sprinkling of degraded white faces.’ The labour press stressed the threat posed by Islander labour to white men’s wages. The Worker provocatively asked Queenslanders whether they wanted their state ‘to be known as Mongrelia’ or ‘Kanakaland’. White labourist solidarity required standing up against the fat man of business and his ‘n***er nourished industry’. By the turn of the twentieth century, the scene was set for drastic action to be taken against the South Sea Islander population.

‘I am afraid of the kanaka and of every black man, because I do not want my race to be contaminated with theirs.’

– Jim Page, Labour Member for Maranoa, House of Representatives Debate, 1901

The governing mantra of early federation politics was the ceaseless quest to make Australia ‘white’. Whilst the term ‘White Australia Policy’ is generally used to refer to the Immigration Restriction Act (1901) and its infamous dictation test, Australian politicians were as fearful of ‘the enemy within’ as of those yet to arrive.

The logic of White Australia demanded the segregation and marginalisation of non-white communities within the nation. This quest culminated in the forced deportation of South Sea Islanders after 1906. The Pacific Island Labourers Act (1901) was one of the first items of business on the agenda of the newly convened Commonwealth Parliament. It provisioned that by March 1904, no new arrivals of South Sea Islanders would be admitted to the country. After 31 December 1906, those remaining in the country who had been born overseas and had arrived after 1879 were to be deported en masse. The act passed in parliament without incident with near unanimous support. The then Attorney General of Australia, Alfred Deakin, noted the close connection between this act and restrictions on migration: ‘the two things go hand in hand and are the necessary complement of a single policy—the policy of securing a ‘white Australia’. Deakin was particularly keen to stress the insights that White Australia had gleaned from the experience of multi-racial democracy in the USA—‘we should be false to the lessons taught us in the great republic of the West’—successful parliamentary democracy required the ‘unity of race’.

The jurist Henry Bournes Higgins delighted in the passage of what he saw as ‘the most vital measure on the programme that the government has put before us’. The few parliamentary voices of criticism came in the Senate, where the Free Traders David Charleston and Josiah Symon referred to the act as ‘a cruel wrong’ (Symon) and an example of the hysteria generated by ‘the White Australian cry’ (Charleston). The press proved slightly more equivocal. The Adelaide Observer, whilst supporting restrictions on immigration noted that ‘If the deportation law should be carried into effect, Australia will be guilty of a monstrous injustice and gross inhumanity’, whilst The Worker (Wagga Wagga) believed it unjust to deport a community which was ‘strikingly intelligent and had a fair mastery of the English language, together with a fair education.’ Other sections of the media voiced criticism along different lines: the terms of the act had not been harsh enough. An anonymous writer in The Bulletin had hoped that the Bill would include a prohibition on inter-racial marriage—‘I hope to see the day when the Australian Parliament will do its bounden duty and make miscegenation a crime punishable by heavy penalties to all parties concerned… I would like to see boiled in oil all those legislators of the Kanaka Prostitute Party who recently voted in favour of non-deportation of those Kanakas living with white women.’ Delays in deportation were attributed by The Bulletin to the ‘spineless, incompetent, unreliable men’ of the Barton government, who lacked the courage to ‘sweep the remaining n***ers into the sea’, and to a conspiracy between the owners of industry and their black workers, as illustrated in the accompanying cartoon.

The response to deportation amongst white workers in Queensland was overwhelming. According to the Brisbane based magazine Truth, upon the announcement of the deportation bill, ‘a feeling of joy thrilled all the white workers of the Queensland sugar districts. At last, their hopes were to be realised and they were no longer to be forced to compete with the black man, or to run the risk of having their wives and daughters assaulted, perhaps murdered.’

**********************************************************

‘Is it really true that white people want to send all boys back to islands, we been work well in this land for white people, then why they want to turn us out?’

– Jack Malayta, Letter to the Brisbane Courier, October 1901

The passage of the Pacific Island Labourers Act was met with spirited resistance from the resident Islander community in Queensland. Two petitions were sent by Islanders to the King and the Governor General in late 1901 and early 1902, carrying the signatures of community leaders. One requested that the Islanders be given permission to lead a ‘quiet and peaceful life in Queensland where most of us have resided for many years’, whilst the other noted the difficulties that returning to their places of origin posed for Islanders: ‘Many of us have been continuously resident in Queensland for upwards of twenty years and during these years our parents and brothers died and we are forgotten there; villages have disappeared and some of our tribes have been exterminated.’

A Pacific Islanders Association was also formed in Mackay by a 30-year-old boarding house proprietor, Henry Tongoa, in 1904. The Association’s meetings across North Queensland regularly attracted audiences of more than 200 people and arranged a march of 100 Islanders through Queen Street in Brisbane in 1907 to receive a hearing by the state’s Home Secretary. Tongoa, with the support of 500 signatories, proposed an alternative arrangement to Deakin in 1906: a reserve could be set aside for South Sea Islanders in a remote area of tropical Australia, where their ‘long history of cultivation could be put to good use’ and they would not be in competition with white workers. Unsurprisingly this proposal was quickly shut down. However, pressure by community groups and plantation owners forced the state government’s hand in 1906 and a Royal Commission was called to investigate possible exemptions to the terms of the act. Islander testimony stressed that many did not wish to return home: they had children in local schools, were members of community churches, had steady employment, and in some instances owned land of their own. Further, many argued that returning home would be dangerous, especially for the ill, old and infirm.

White plantation owners additionally signalled that the end of the labour trade would spell the death of the sugar industry in Queensland, depriving farms of their inexpensive workforce. In response, the Royal Commission recommended that a number of exemptions be given to Islanders who were enrolled in educational institutions or had intermarried in their communities. More significantly, fears of industrialists and plantation owners were allayed by the government’s provision of fiscal protection and ‘white labour’ incentives in the industry. A protective duty of £6 per ton was placed on sugar imports, and, to encourage European labour, £2 of a £3 pound excise placed on Australian produced sugar would be refunded on sugar manufactured from cane grown and harvested solely by Europeans. The cultural imperatives of the White Australia project were thus to be buttressed by an incipient economic nationalism.

**********************************************************

‘Within a short space of time now, the walkabout kanaka and the work-a-day kanaka in Queensland will be but a memory of bygone days.’

– The Brisbane Telegraph, 8 December 1906

With the preconditions for deportation set in place, the action was swiftly taken to round up remaining Islanders for transportation to Brisbane or the sugar ports of coastal North Queensland. The Pacific Island Department of Queensland was to be paid £5 per head for each Islander deported. In order to avoid ‘trouble’, it was acknowledged that ‘the deportation should be commenced at once on a large scale and carried out regularly until the work is completed.’ Islanders from the New Hebrides (Vanuatu) were to be separated from those from the Solomon Islands to avoid conflict at the ports, and punishment was to be meted out to those who disobeyed embarkation orders.

Whilst the majority of Islanders complied with the deportation orders, it is thought that up to a hundred fled inland to escape police raids. One Islander reputedly lived in the hills south of Cardwell for 30 years until he was apprehended and sent to an Aboriginal reserve, whilst in Innisfail, a European hid a ‘favourite servant’ for weeks in the bush and supplied him with food. To finance the deportation, the Commonwealth government put pressure on employers to pay for shipping costs. This proposal met with significant resistance, forcing the government to turn to a more nefarious solution. In the 1880s, the Queensland government had established a Pacific Islanders’ fund, which paid the wages of deceased labourers to their families in the islands. Only 16% of these funds would reach their destination. The remainder of the money was returned to the Queensland Treasury and duly put towards meeting the costs of deportation. Islanders left Queensland in large numbers, filled with spite and resentment. Departing Malaita passengers on board one steamship issued a defiant farewell: ‘Goodbye White Australia; Goodbye Queensland; Goodbye Christians’.

**********************************************************

‘Human solidarity does not mean the mixing of all the races of mankind in the mortar, and the extinction of race, colour, and character.’

– The Tocsin, 1901

With the deportation of two-thirds of Australia’s South Sea Islander community came the destruction of a once lively community and much of its cultural memory. Yet those who remained kept the stories of the departed alive. Many were never able to let go of the trauma which accompanied saying permanent goodbyes to friends, colleagues and family members on the docks of Brisbane, Mackay and Bowen. Their testimony bears witness to the hypocrisy of the White Australia project. In one of the most harrowing pieces of evidence given to the Royal Commission of 1906, a Lifu Islander from North Rockhampton offered an apt summary: ‘We are very sorry, and we have plenty feeling. We know white people don’t like black men in this country and hate the sight of us… these boys no come from the islands by their own will. Ship comes to the islands and make fool of them and fetch them to this country…I am ashamed to think you drive away people like that. That is a thing I would not do.’