Being one of India’s largest cultural exports, Bollywood has undeniably played a major role in shaping the national identity and international image of India. The cultural pervasivity is almost inescapable, as the industry’s biggest stars can be seen plastered on every street. They populate the public consciousness, making appearances in every form of media from soap commercials to being the owners of popular IPL cricket teams.

Each language in India has its own film industry with its own cult following of prolific actors. These amount to around 28 unique industries, representing a different language or dialect and producing around 200 films per year. This creates an idiosyncratic climate where there are usually 5-6 films of different origin playing in the same theatre. However, behind the glitz and glamour, there is an element to Bollywood that is inherently detrimental to the cultural diversity of what was once a multifarious film industry.

The often normative effect that Bollywood plays on smaller Indian screen cultures such as Tollywood (the Telugu film industry) and Kollywood (the Tamil film industry) and the advent of the “Masala” film genre has diluted the once thriving and unique film industries. Coupled with this, the industry is plagued with rampant plagiarism, with some plots being directly lifted from Hollywood, and even entire songs being stolen to be produced as a degraded rendition. Furthermore, individuals are able to make entire careers out of these practices profiting immensely by India’s relaxed to non-existent copyright laws .

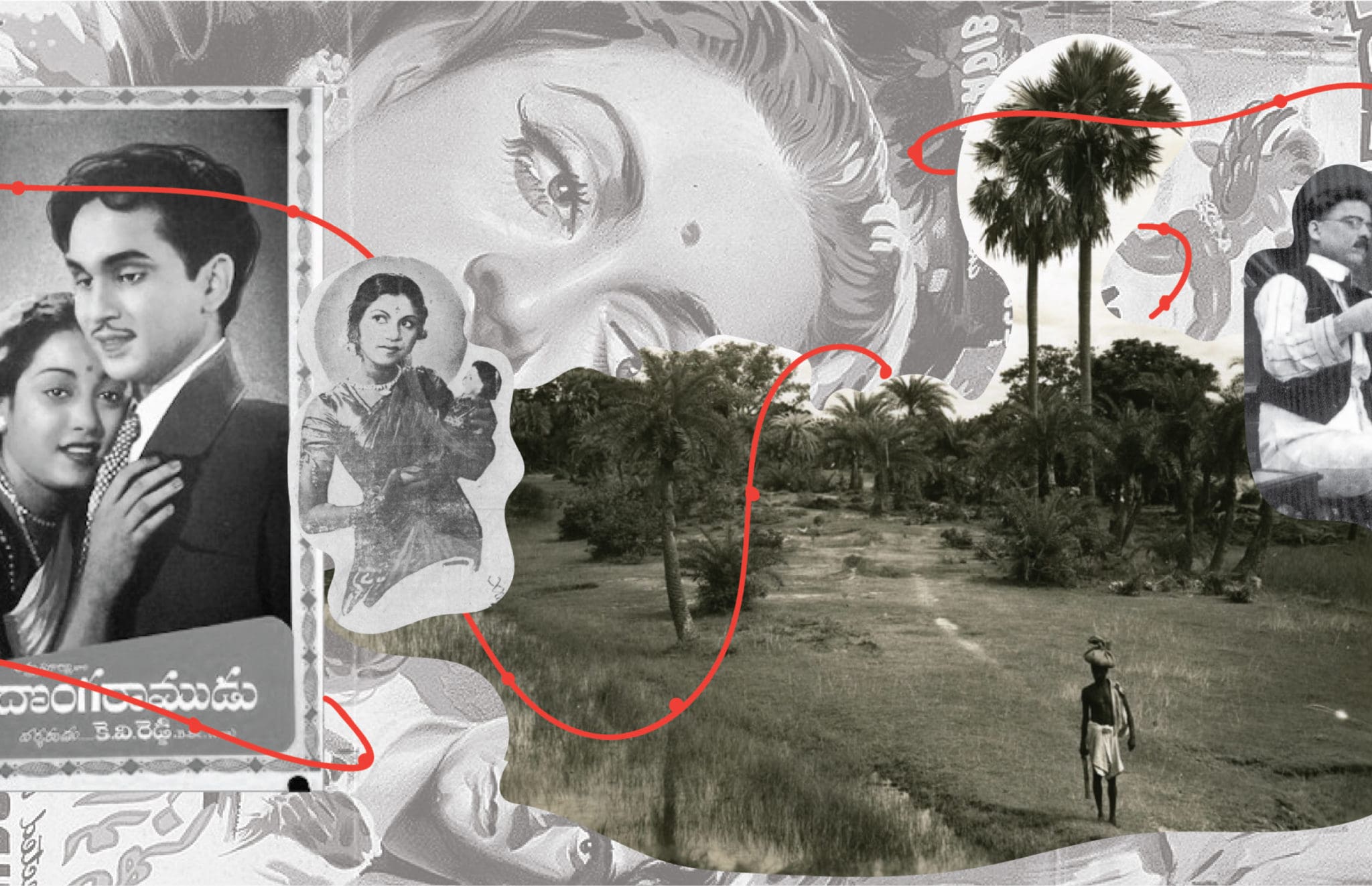

The immense amount of cultural hegemony that the Bollywood industry holds is reflected in the normative effect that it bears on all other film industries: it is often the case that other Indian film industries take after Bollywood specifically in terms of format and style, adapting as many elements as they can to mirror Bollywood film. This wasn’t always the case. In the early stages of Indian cinema, each language developed its own unique industry for film.

The Indian film industry was birthed in the midst of a British Raj (Colonial India): beginning in the art of silent films it then inspired filmmakers around the country to create their own visions in this artform. Many of the plots of these films drew from ancient poems, folklore and traditional plays from Parsi and traditional Hindu theatre. Dadasaheb Phalke was the first to produce a full length film, and is considered the original pioneer of Indian cinema. His movie ‘Raja Harishchandra’ (1913), depicted a religious parable and set the precedent for most early films bringing religious narratives to the screen. The film premiered in Mumbai with intertitles produced in Hindi, English and Marathi.

On the 15th of June, 1947 India achieved independence from the British Empire, also separating Pakistan as its own independent nation. As a consequence, the culture and arts sector of the country dove into what is considered the ‘Golden Age’ of Bollywood cinema. Filmmakers depicted themes of working life, urban social struggles, political conflicts – it painted the new India that was anti-colonial and independent, in its own unique cultural brush. Notable classics include ‘Pyaasa’ (1957) by Guru Dutt, which depicts the romance between a struggling poet and a sex worker. Another exemplar is Raj Kapoor’s ‘Shree 420’, produced in 1955, illustrating the wishful hopes of a young boy from country Allahabad who pursues his dreams in the big city.

The popularity of film in India was also evident in the flourishing of films that were produced by, and for, its multifaceted cultural and linguistic groups. The Tamil industry had its own equivalent in Kollywood, as with the Telugu industry in Tollywood. Tollywood, in particular, saw its roots in the renowned director Raghupati Venkaiah who is considered the father of Telugu film. The 1930s saw the beginning of a large following in Telugu films, propelling the film, its actors and directors into the mainstream. Telugu films would often centre around heavily politicised plots, delving into revolutionary undertones, even going insofar as to depict uprisings against the British Raj and highlighting the social friction spurred by the caste system. ‘Raithu Bidda’, produced in 1939 by Gudavalli Ramabraham, explored the historical uprising of peasants against their aristocratic landowners who were particularly powerful due to their relationship with British colonial imperialists who bestowed them ‘princes’. This film was banned by the British Raj. However by the time the 1950s and 1960s rolled around, the films became evidently less provocative, and appealed more to undemanding plotlines, jovial theatrics and music, and heroic male protagonists. Yet an almost cultural renaissance emerged during the 70’s and 80’s where movies such as “Sankarabharanam” and “Maa Bhoomi” reignited the social and political genre of film that was once thought to be extinct. These films were landmark developments within the industry creating a distinct brand for Telugu films.

Despite a history of unique and vibrant film cultures, the once diverse industries slowly started producing the same genre of film over and over again, the “Masala” film. The advent of this type of film revolutionised not just its progenitor, Bollywood, but all Indian film industries, setting the tone for films for the next five decades to come. It was first experimented with in the mid 1970’s in films such as Sholay (1975) where it became wildly successful. This type of film became increasingly popular during the 90’s to such a large extent that almost every other genre, bar horror, was choked out of theatres. By the turn of the century, films under this genre, such as “Munna Bhai MBBS”, “Rang De Basanti” and “Dhoom”, were wildly successful.

Almost all industries picked up this genre and started producing such films en masse, creating the formulaic homogeneity that Indian films are all too well known for in the present day. This was all at the expense of killing off the unique subcultures that each industry had developed. The rapid adoption and extreme saturation of the “Masala” genre can be linked to many factors, the most obvious being the cultural capital that Hindi has in India; it was once a language only spoken in the north of India and the rest of the populus was not privy to the language or had no exposure to it. This allowed for distinct cultures to emerge in their own language bubbles in each region, a phenomenon reflected in the film industries early on each language had its own screen culture. In more recent times, the blurring of cultural lines via the advent of instant communication and the increasing cultural hegemony of Hindi has resulted in film industries taking a similarly normative turn, caving into demands from audiences who crave the next “Bollywood style film” in their own language.

Along with the domineering effect that Bollywood has on its sister industries, it has also fallen prey to a dangerous practice of plagiarism. This phenomenon is relatively new, originating in the 1970s often stealing from prolific Hollywood films, taking all but the actors and language. An early example of this practice was “Dharmata” (1975) where the plot was taken from Francis Ford Coppola’s “The Godfather” (1972) and proceeded to be well received by the largely unaware audiences at the time. This is but one of many plagiarised films and, according to one study, there are well over 300 films that have been plagiarised. This practice is in fact becoming even more prevalent despite the tightening of copyright laws.

The lucrative nature of plagiarised films attracts many directors as it is relatively low effort to steal the script of another successful film, and box office success is already assured. One such director is Vikram Bhatt, director of ‘Raaz’ (2002), a remake of ‘What Lies Beneath’ (2000), and ‘Kasoor’ (2001), a remake of ‘Jagged Edge’ (1985). Bhatt has blamed the audiences and their desire for ‘American culture’ and pressure from the producers wanting multiple blockbuster films within months of each other, stating, “Financially, I would be more secure knowing that a particular piece of work has already done well at the box office. Copying is endemic everywhere in India. Our TV shows are adaptations of American programmes. We want their films, their cars, their planes, their Diet Cokes and also their attitude. The American way of life is creeping into our culture.” This predatory practice of feeding unknowing audiences repackaged and stolen media is even more prevalent in the Bollywood music industry. Despite their immense popularity, the Indian music industry had no hesitation in directly plagiarising iconic foreign songs such as Wham!’s “Last Christmas”, the “Macarena”, the main theme from ‘The Godfather’, and ABBA’s “Fernando”. It was no coincidence that this explosion of plagiarism was set off after the introduction of cable television in India. It made the hegemonic US film industry far more accessible to the populus, with cultural homogenising an inevitable consequence. This phenomenon seeps through the fabric of arts and culture in India.

The lack of artistic integrity that pervades the mainstream entertainment industry begs the question as to why such practices are allowed to occur. The industries are undeniably nepotistic in their functioning – actors are cast by their own family, films funded by royalty and dynastic family powers. Ultimately, at the root of Bollywood’s unabashed plagiarism lies profit. The international film world in the late 80’s and 90’s had not yet familiarised themselves with the still obscure Indian film industry. This brewed the perfect conditions for money-centric industries to easily appropriate blockbusters and turn them into their own, only with Indian actors speaking Hindi rather than English. Under Section 52 of The Copyright Act 1957 of the Indian Constitution, an individual may reuse copyrighted work, if limited and used for specific purposes. This vague and easily manipulated law has irrevocably been jumped over by Bollywood, time and time again.

The Indian film industry has undertaken many transformations, adapting to its constantly transforming, international context. However, it has been distastefully mired in both its Bollywood centric prevalence and the rampant plagiarism that has diluted originality and artistic creativity. Having its beginnings in the British Raj, to finally being liberated from its colonial bindings, and eventually entering the capitalist boom as a major world power, the artistic achievements of the country’s most prolific and game changing filmmakers and actors should be applauded. Films serve to reflect the world around us, and India’s best films have driven cultural, social, political boundaries to achieve just that.