The antiquated English aristocracy up in arms against the pedestrian American nouveau rich? Is the Earl of Marshwood holding a riding crop, or is that something more sensual? How many more martinis can Ms Moxton stomach? This comedy of manners delivers a blow-by-blow breakdown of the English class system when it is threatened by illustrious intruders and shady past lives.

SUDS’ performance of a slightly abridged Relative Values walks a well-trodden path — Noël Coward’s lighthearted three-act comedy deals chiefly in the humour to be found in social class tension, separation and confrontation. Nigel, the Earl of Marshwood, is due to return home from abroad with his Hollywood has-been and bride-to-be Miranda Fayle in tow. Countess of the estate, Felicity, is suspicious, the head butler Frederick Crestwell isn’t having a bar of it, and maid Moxie has her own reasons for hoping that this marriage never sees the light of day. From here on in it’s scandal after scandal as dirty laundry is aired and all manner of tea is spilled.

Walking into the Cellar Theatre feels like taking a step back in time. Bradie Tato’s set design evokes both the imposing grandeur expected of a stately manor, and the burgeoning obsolescence of a Union Jack in the corner and an antique spoon collection on the wall. Like the Marshwood establishment’s sense of self-importance, the set where most of the play takes place feels more at home in the mid-1800s than the play’s actual 20th century timeline. Taking my seat in the top row of a tiered seating setup – nearly bumping into a ceiling light fixture in the process – it feels like the audience are voyeurs to the thrill of these tantalising petty squabbles.

In terms of performance, the story demands razor-sharp dialogue delivery in order to retain a comically tempestuous tone. Unfortunately, this parameter made evident a number of inconsistencies and shortcomings. Although lines were certainly thrown out at a fast pace, this was frequently at the expense of both clarity and comedic timing. On a number of occasions when characters had to restart their lines entirely, the punchiness of the rapid-fire jokes fell a little flat.

That said, there are a number of moments and characters that result in genuine uproar. Marlow Hurst’s Crestwell is a definite highlight, always quick to employ gleeful and florid condescension towards any situation, both to diffuse drama and create it. Similarly, Zoe Clarke as Felicity brings a sense of sophistication to the role, her portrayal of the character successfully cavalier yet concerned about the prospect of her troublesome son ‘marrying beneath him’. The way both Hurst and Clarke physicalise the being of their characters – uptight and graceful respectively – drives home both their conviction and awareness of comedic timing. Of singular mention, however, is Natasha Nogueira’s Ms Moxton. In a climactic scene, after a number of martinis, she breaks her usually timid nature to decry the lies and deceit of everyone around her in a standout moment. Another favourite moment is an earlier scene wherein Miranda relays her melodramatic backstory to the rest of the household; made even more entertaining by lighting designer Sophie Morrissey’s choice to reduce to a spotlight on the actress, framing the speech as a proverbial ‘close-up’ moment.

The momentum that the play does manage to build in its first two acts is sadly diminished somewhat in the third, as both alienating blocking choices and noticeable lapses in accent — both American and British — jar some of the more serious moments of the concluding events. There is also a sense of apathy to their final choices that contrasts to the magnitude of their implications. Fortunately though, amidst its hiccups, Relative Values remains thematically unimpaired, purveying a sardonic point for the social status quo — much to Moxie and Crestwell’s pleasure.

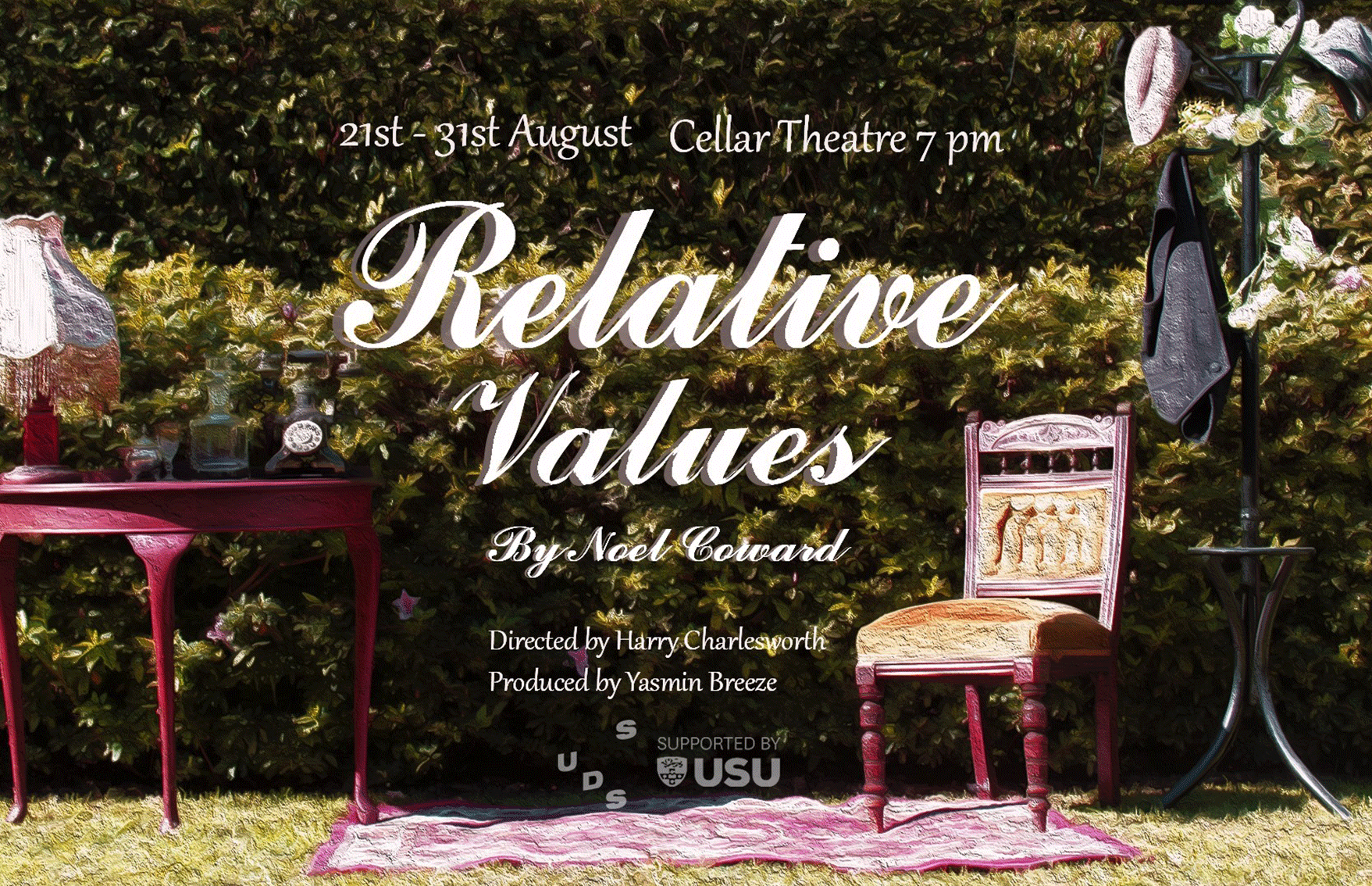

Relative Values enters its second week from 28 to 31 August at 7pm. Buy tickets here.