The issue of whether art galleries should show works by morally contentious artists has permeated discussion in the art community over the last several decades. For galleries, there seems to be no easy path to take; they are damned if they do and damned if they don’t, facing backlash both when they censor art and when they don’t. In the case that we did decide to censor morally contentious artists, who would be the arbiter of such censorship anyway? Is objective censorship even possible or will it always be subject to capricious surges of public opinion?

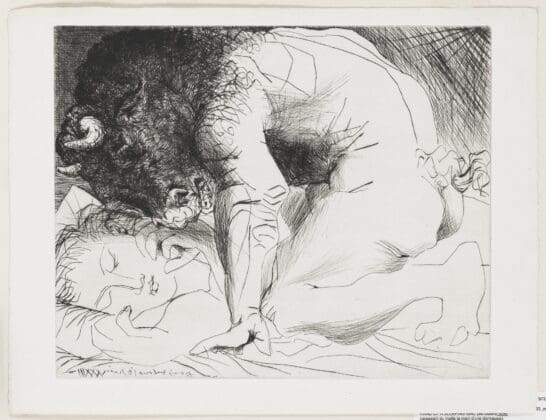

It is an unfortunate reality that if we were to suddenly decide to remove and censor the works of all the world’s morally condemnable artists, there would be myriad blank walls in our galleries. In addition to this, it would become very difficult to teach the history of art without being able to examine the works of these artists. For instance, just as it would be impossible to tell the history of the Western world without reference to Adolf Hitler, how could one hope to teach Cubism without including Pablo Picasso? A number of works featured in Picasso’s Vollard Suite, comprising 100 intaglio prints, depict animalistic scenes of rape and murder. Perhaps the most tormenting of the prints, however, is Minotaur Caressing a Sleeping Woman (1933). The work shows a Minotaur hunched over a sleeping woman as it caresses her cheek. Its taurine face, rendered in incredible detail and in stark contrast to the line drawing of the rest of the print, rests gently on its own hand, showing a deep agony bordering on self-hatred.

Sally Foster, of the National Art Gallery of Australia, notes that Picasso saw himself as the Minotaur and through the work attempts to portray his struggle with the “animalistic urges” that both plagued and devastated him during his life. “He doesn’t hide it,” says Foster. “He’s not being secretive about it, he puts all his psychological tensions…in his work for all of us to see.” Whilst it is not the singular purpose of art, great artworks often share the quality of being able to authentically describe the world we live in, and offer insight into either our own lives, or broader human experiences. A depiction of Picasso’s internal torments, fraught with the dichotomies of pain and desire, pleasure and self-loathing, Minotaur Caressing a Sleeping Woman is but one example of art that is so painfully honest in its twisted portrayal of human nature that it must be seen by the world. To exclude the likes of Picasso from galleries would not just make it impossible to do justice to the history of most art movements but also deny us the opportunity of learning what these pieces tell us about the darkest parts of human history and experiences.

It is important to recognise also that the folly of the ‘separating art from artist’ debate often clouds the discussion that we are having around whether or not to show the works of morally condemnable artists. It is folly because of course we should never view a work as separate from its artist — to do so would be to ignore the fact that understanding the artist is an integral part of understanding the art. New York artist and editor of Silica Magazine, Shannon Lee is dismayed that: “the artistic canon has consistently disregarded [Picasso’s] personal tumult with women in favor of keeping the ‘art separate from the artist.’” She continues: “If anything, an artist’s flaws ought to provide us with potential opportunities to revisit and re-contextualize their work.”

The experience of viewing a work of art on an aesthetic level, in combination with an education around the context of the artist, including any potential ethical issues, allows for a much deeper understanding of the work as a whole. If we were to look at Picasso’s Minotaur Caressing a Sleeping Woman on a simply aesthetic level, it would be a skillful, albeit deeply disturbing work of art. However, if we understand it as an exploration of human nature and an authentic insight into the self-loathing produced by acting on animalistic instinct, it becomes a triumph of artistic skill from which it is difficult to look away. Whilst I won’t argue in an absolute sense against the censorship of art, I would err on the side of allowing humanity to learn from these works.