The Pillowman by Martin McDonagh is a play about stories. All four of the characters emphasise the importance of fiction in their lives, with each portraying their unique experience with literary conventions. Katurian (Annie Mosse) is a writer within whose stories lie his quest for immortality. Michal (Gen Papadopoulos) lets his brother’s stories dictate his actions to the point of no return. Detective Tupolski (Tom Hanaee) is far prouder of the single story he has written than any of his police work. Detective Ariel (Yarno Rohling) is, affectionately, a sucker for a happy ending.

Sydney University Dramatic Society (SUDS) is no stranger to heavy shows with long lists of content warnings. However, The Pillowman was the first from memory that provided the seated audience with five minutes to speak with a crew member or leave the theatre after producer Alex Bryant read out the content warnings.

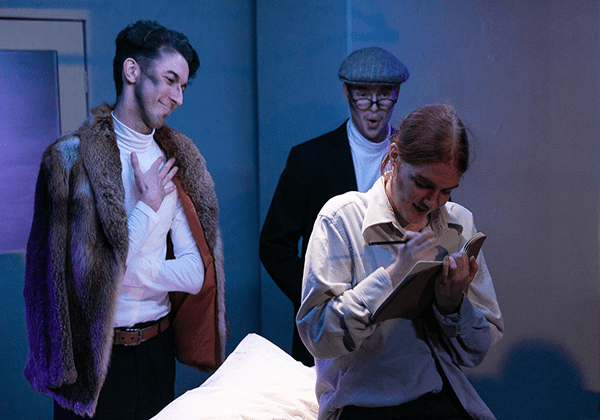

The Cellar Theatre was washed in white. The stage was modestly adorned with a block table, a couple of chairs, and an LED square light hanging from the ceiling, mimicking an interrogation room. The play is set in an unnamed totalitarian state, but its characters and conventions mirror our own in ways that highlight the power imbalances and discriminatory qualities of our justice systems.

Oliver Durbidge’s (director) rendition of the play is a haunting ode to the fears people think they leave behind when they outgrow bedtime stories. In some way, all four characters are plagued by their pasts. Hanaee and Rohling play off each other with a classic ‘good cop, bad cop’ routine, though it is not apparent whose character fills which role on the surface. Mosse’s Katurian offers range in his pursuit of twisted fantasies, with the biggestbeing his relentless proclamation that he “isn’t trying to say anything” with his writing. Papadopoulos is seamless in how she depicts the innocence and rot at the core of Michal’s character. Additionally, it is important to note that Mosse and Papadopoulos expertly captured an argument between siblings even when the subject matter related to child murder and torture. No matter how little or long they were on stage, no character came across as a filler or a stand-in with a designated role. The direction and acting peeled away each individual’s layers and lay them bare for the audience to see.

There is not much room in the Cellar Theatre. It is, essentially, in a basement with no natural light permeating the space during performances. I have not seen much experimentation in regards to expanding the space beyond the walls of the theatre. That being said, the show’s audiovisual aspects were brilliantly shot and animated by Kath Thomas and Eoin O’Sullivan. Katurian’s stories were read out by Mosse’s disembodied voice offstage, with projectors visualising animated, video game-like and ‘draw my life’-esque scenes from the narratives. However, one story that acted as a flashback to Katurian and Michal’s childhood (titled ‘The Writer and The Writer’s Brother’) was filmed by Durbidge and played simultaneously alongside a section of the performance. It appeared to be filmed in real-time, with the actors matching their on-screen counterparts almost precisely.

All in all, The Pillowman doesn’t pretend to be a lesson in morality or a blueprint for what is good. It is a play about stories, living through traumatic experiences, and the complications we hide behind fiction.

CONTENT WARNINGS FOR THE PLAY:

Violence including police brutality, gore, explicit language including anti-semitic and ableist language, references to child abuse, descriptions of child murder, descriptions of suicide, references to murder, depiction of murder, references to sexual assault of a minor, references to alcoholism, simulated use of a firearm and strobe lighting.

The Pillowman runs until Saturday the 27th of March at the Cellar Theatre.