Walking through the streets of Sydney, it is very easy to feel separated from nature. But amongst the concrete and bitumen, the natural world survives. During the 2021 lockdown, I tried to spend more time in urban nature by cycling within my 5 km radius, and found myself repeatedly drawn back to the Whites Creek wetlands, nestled within the Inner West suburb of Annandale.

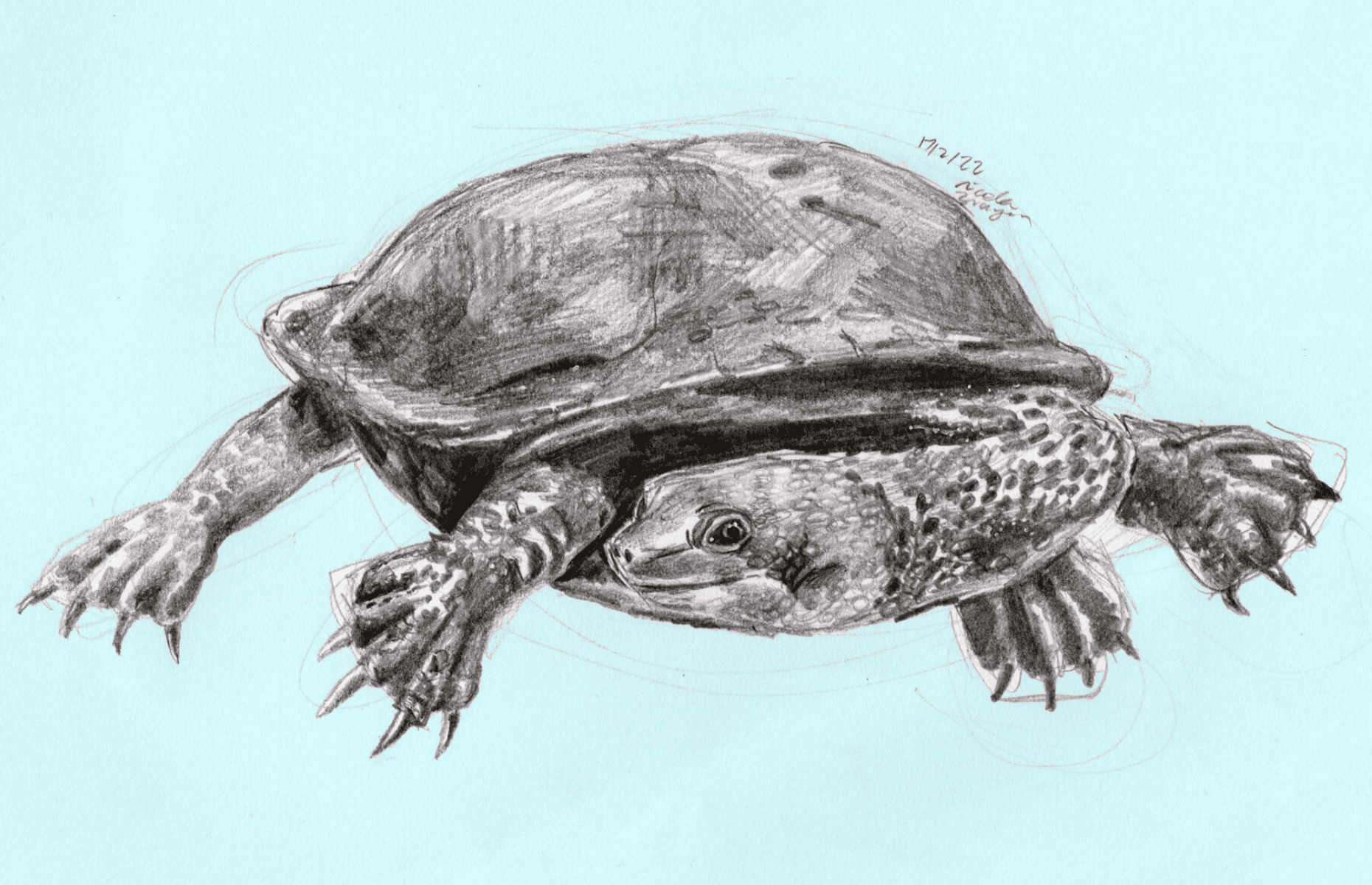

My cycling trips were encouraged by some friendly faces who call the wetlands home: a population of Eastern Long-Necked Turtles. Yes, wild turtles living in the centre of Sydney. This population of turtles was not introduced into the area. Instead, they moved into the wetlands of their own accord shortly after their construction, affirming the popular idiom from the 1989 film Field of Dreams: “If you build it, they will come”.

The turtle’s current habitat, Whites Creek wetlands, is one of Sydney oldest stormwater canals, with the construction of its concrete walls starting as early as 1898. While technically a creek, the canal functioned as a stormwater drain, sandwiched between desolate pools of brackish water laden with mosquito larvae. It remained this way until 1994 when local citizen and Earth Friends member Ted Lloyd organised community support for the construction of the wetlands. Eight years later, the project was completed. Since then, the wetlands have been home to some of Sydney’s most beautiful flora and fauna.

What I find most interesting about the Annandale turtles is how they challenge the notion that cities are outside nature. Colonial practises have disconnected us from the land on which we live; now, we view the city as purely a human place. In reality, Sydneysiders still live amidst nature. Given the turtles were not introduced to the area, one must question how they got to Whites Creek. Perhaps they were lurking just out of eyeshot.

If so, what other species could exist within our dense urban understory hiding beyond human perception?

Animals are no strangers to urban environments. The highest density of foxes across England is in London and Bournemouth. We are all aware of urban wildlife, yet Sydney’s rich urban ecology is still underappreciated. We are lucky enough to have large white birds that resemble pterodactyls (Ibis), bats that hang like vampires in the night, and two adorable possum species.

As a result of long-term colonial processes, changes to now-urban landscapes have pushed once widespread native animals into small pockets of habitat across Sydney. Additionally, certain introduced species, such as foxes, thrive in urban environments and accordingly outcompete native species.

Even our friends, the long-necked turtles, are threatened by an equivalent American species, the Red-eared slider turtle. This turtle is listed as one of the most invasive in the world by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Local ecologists are worried it could find its way to Whites Creek wetlands. While the Eastern long-necked turtle is not a threatened species, it is uncommon in urban environments. It would be a shame to lose this relatively new population to an invasive species that could disrupt the local ecosystem.

Urban geographer David Harvey once claimed, “there is nothing unnatural about New York City”. This sentiment particularly resonates with me when thinking of the turtle population in Annandale. No matter how grey, dirty, loud, and artificial the city may seem, small pockets of urban ecology still find a way.

Part of understanding the city’s social and ecological capacity is to recognise that seemingly human-exclusive processes will doubtlessly impact the natural environment and non-human actors. Unfortunately, the perceived separation of nature from society leads to arrogant and anthropocentric oversights; seeing the environment as something that exists alongside humankind, rather than something unto which humans can impose their will, should be respected and appreciated.

Although humans have historically and continue to negatively affect the natural environment, when pockets of habitat within urban environments are returned to their pre-colonial state, native flora and fauna will follow. Urban turtles not two kilometres from our inner-city campus prove this theory. I recommend strolling down to Whites Creek wetland in the morning or early afternoon to marvel at the inner-city turtles sunbathing. You may just realise our city isn’t as unnatural as it seems.