I once asked my mother what it meant to be bilingual. I had just seen get off a work call with one of her clients, explaining the intricacies of insurance policy in perfect English. The next minute, she was on the phone with my grandparents, talking in clipped Tagalog about their upcoming doctor’s appointment. When she finally got off the phone, she told me that being bilingual meant more than just fluency in two languages. It also entailed the state of one’s mind, the ability to rapidly translate one’s thoughts into the language that others could best understand.

As someone who was studying a language at the time, this idea intrigued me. I asked her if she thought of things in English before translating them to Tagalog in speaking.

“No,” she replied. “The opposite.”

I’ve been learning and speaking English since my earliest years in Australia. Although I was inevitably exposed to Tagalog by virtue of growing up in a Filipino household, I was constantly reminded as a toddler, and then a kindergarten student, to use English instead of Tagalog in expressing myself. Soon enough, the reminders stopped. By the time I was six, every word that came out of my mouth was in English.

Every migrant knows what it means to be an outsider. And every migrant knows the desire to fit in. To assimilate into the ‘new’ country is an ideal, something to strive towards. It’s seen as a marker of success. A significant part of that is fluency in English.

But the thing about assimilation is that it necessarily entails chipping away at one’s native culture to create space for the new one. And in a country like Australia that continues to uphold the colonial project started by European settlers, assimilation is intertwined with the ideal of whiteness. This is the implicit message that all Australian migrants have internalised – the whiter you code yourself, the more successful you are at fitting in.

I’ve spent my entire schooling life perfecting my English. But to gain fluency in a language also means reprogramming your brain to think in that language. And as I’ve learned how to craft beautiful sentences of prose, or articulate complex ideas in simpler words, I’ve neglected the part of myself that could think in Tagalog – that conceived of myself as Filipino.

Recently, I’ve started learning Tagalog again. Firstly, out of a sense of necessity for my job (being responsible for Honi’s multilingual section), but then out of a desire to dismantle the damaging effects of assimilation. Fluency entails more than just speaking and understanding, but also regaining an appreciation for the behaviours, attitudes and values I had discarded long ago.

But it’s not enough for me that these ideas are articulated in the language of my assimilation. To continue reclaiming the identity I have lost, I must also reclaim my mother’s language as my own.

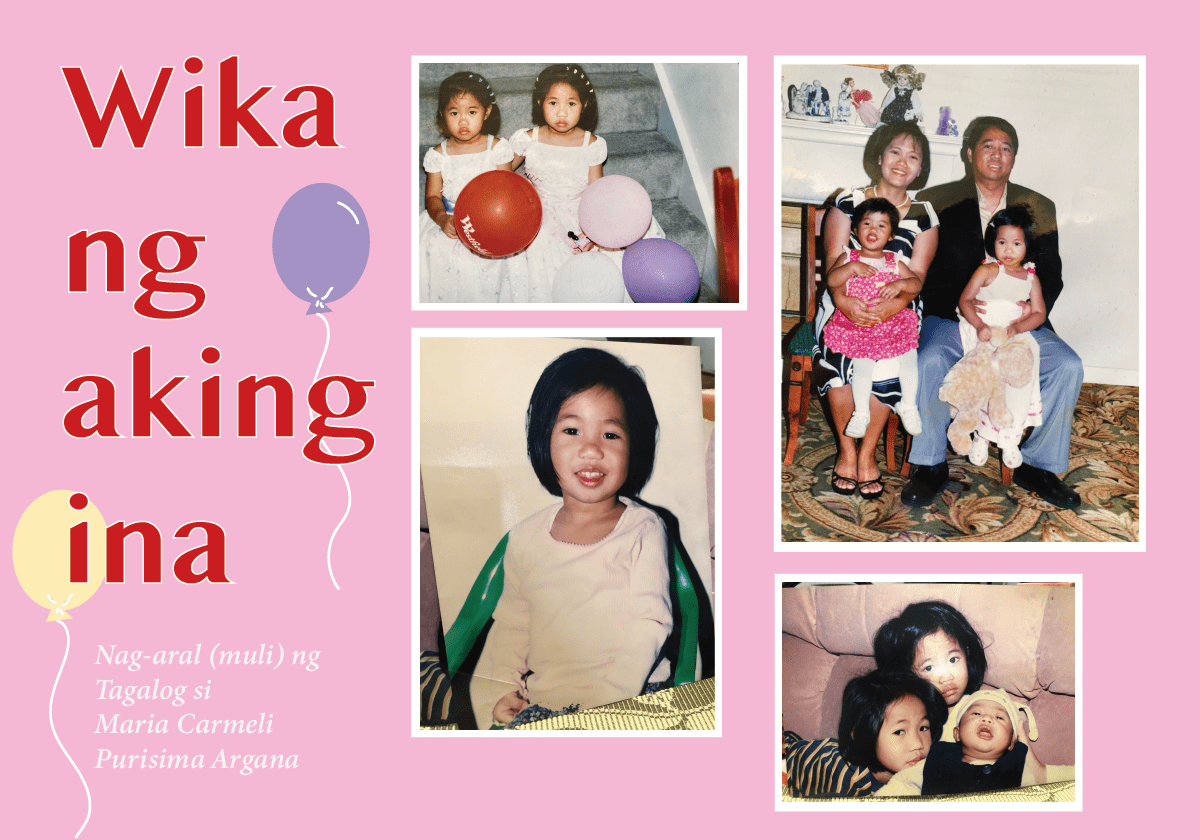

Wika ng aking ina

Translation by Cynthia Argana.

Nag-aral (muli) ng Tagalog si Carmeli Argana.

Minsan tinanong ko ang aking ina kung ano ba ang kahulugan ng pagiging bilingwal. Ito’y matapos kong marinig kung paano nya ipinaliwanag nang mahusay sa wikang Ingles ang masalimuot na kalarakaran ng insurance sa kausap nya sa telepono. At pagkatapos noon, Tagalog na Tagalog naman sya sa pikikipag-usap sa ang aking lolo at lola tungkol sa kanilang appointment sa doktor. Sabi nya sa akin, ang pagiging bilingwal ay higit pa sa kakayahang makipagtalastasan sa dalawang wika. Kasama din dito ang kalagayan ng pag-iisip, ang kakayahang dagling maisalin ang mga saloobin sa mga salitang pinakamadaling maunawaan ng iba.

Bilang mag-aaral ng bagong lenguahe nang mga panahong iyon, naintriga ako. Tinanong ko sya kung nag-iisip ba sya sa Ingles bago magsalin at magsalita ng Tagalog.

“Hindi,” sagot nya. “Baligtad.”

Ingles na ang salitang inaaral at ginagamit ko sa pagsasalita magbuhat ng dumating kami dito sa Australia. Kahit pa di maiiwasang lantad ang Tagalog sa aking paglaki bilang bahagi ng pamilyang Pilipino, mula pagkabata hanggang sa pagtungtong sa kindergarten, lagi ang paalala sa akin na mangusap sa Ingles. Di malaon, natigil din ang mga paalala. Sapagkat sa gulang na anim na taon, pawang Ingles na ang lahat ng katagang lumalabas sa aking bibig.

Alam ng lahat ng migrante kung paano maging dayuhan. At alam din ng bawat migrante ang pagnanais na mapabilang. Ang mapasanib sa ‘bagong’ hirang na bayan ay ideyal at bagay na pagsusumikapan, isang batayan ng pagiging matagumpay. Isang malaking bahagi nito ang pagiging matatas sa wikang Ingles.

Subalit sa pagsasanib, kailangan din ng pagtatastas sa kinagisnang kultura upang magbigay puwang sa pagtanggap sa bago. At sa isang bansang katulad ng Australia na patuloy na tumatangkilik sa proyektong kolonyal na sinimulan ng mga Europeong dayo dito, ang pagsasanib ay nakabigkis din sa ideyal ng pagiging puti. Kung mas maibabanghay mo ang iyong sarili sa pagiging puti, mas mapagtatagumpayan mong mapasanib sa bagong hirang na bayan—ito ang hindi lantad na mensahe na unti-unting nanuot sa pag-iisip ng mga migrante.

Ang mahabang panahong ginugol ko sa pag-aaral ay sya ring oras na ginugol ko upang ma-perpekto ang paggamit ng wikang Ingles. Subalit ang makamit ang katatasan na ito ay kaakibat din ng pagdiin sa utak na mag-isip sa wikang ganito. Kayat habang natututo akong lumikha ng magagandang sanaysay, bumaybay sa masalimuot na mga ideya at balangkasin ito sa mga payak na pangungusap, napabayaan ko ang bahagi ng aking pagkatao na kayang mag-isip sa Tagalog—yaong makakapagbadya sa aking pagiging Pilipino.

Kamakailan ay nagsimula uli akong mag-aral ng Tagalog. Una, dala ng pangangailangan sa trabaho (bilang tagapangasiwa ng multilingual section ng Honi) subalit dahil na rin sa kagustuhan kong buwagin ang mapanirang epekto ng pagsasanib. Ang pagiging matatas sa wika ay higit pa sa pagsasalita at pag-unawa, kundi ang pagbawi din sa pagtanggap sa mga pag-uugali, gawi at pagpapahalaga na naisantabi ko sa mahabang panahon.

At hindi lamang sapat na ang mga saloobing ito ay naisalita ko sa wika ng aking pinagsaniban. Upang patuloy na mabawi ang identidad na nawala sa akin, kailangan din ang muling pag-angkin sa wika ng aking Ina billang sarili kong wika.