This past summer, our garden’s resident orb weaver spider decided to erect its web directly in front of our door. The web was huge – at least a metre in all directions – and its centre had the exact coordinates to meet the eyeline of, say, a hapless 23 year-old stepping out to begin his day. In an instant, both of our plans were waylaid and the next 15 minutes were spent tearing silk out of my beard. Written off as a one-time trauma, it soon became a waking nightmare as the same thing happened the next day, and then the day after, and the day after that…

Now cluey to the situation, I tried to respect the spider’s handiwork: by slicing the supporting strands close to their footholds, I could gently fold the web inwards like a fitted sheet. After all, some orb weavers eat old silk to conserve nutrients, and this was the least I could do to replace a day’s lost flies. In return, the spider emerged overnight and dutifully spun another web, at face height, right in front of the door.

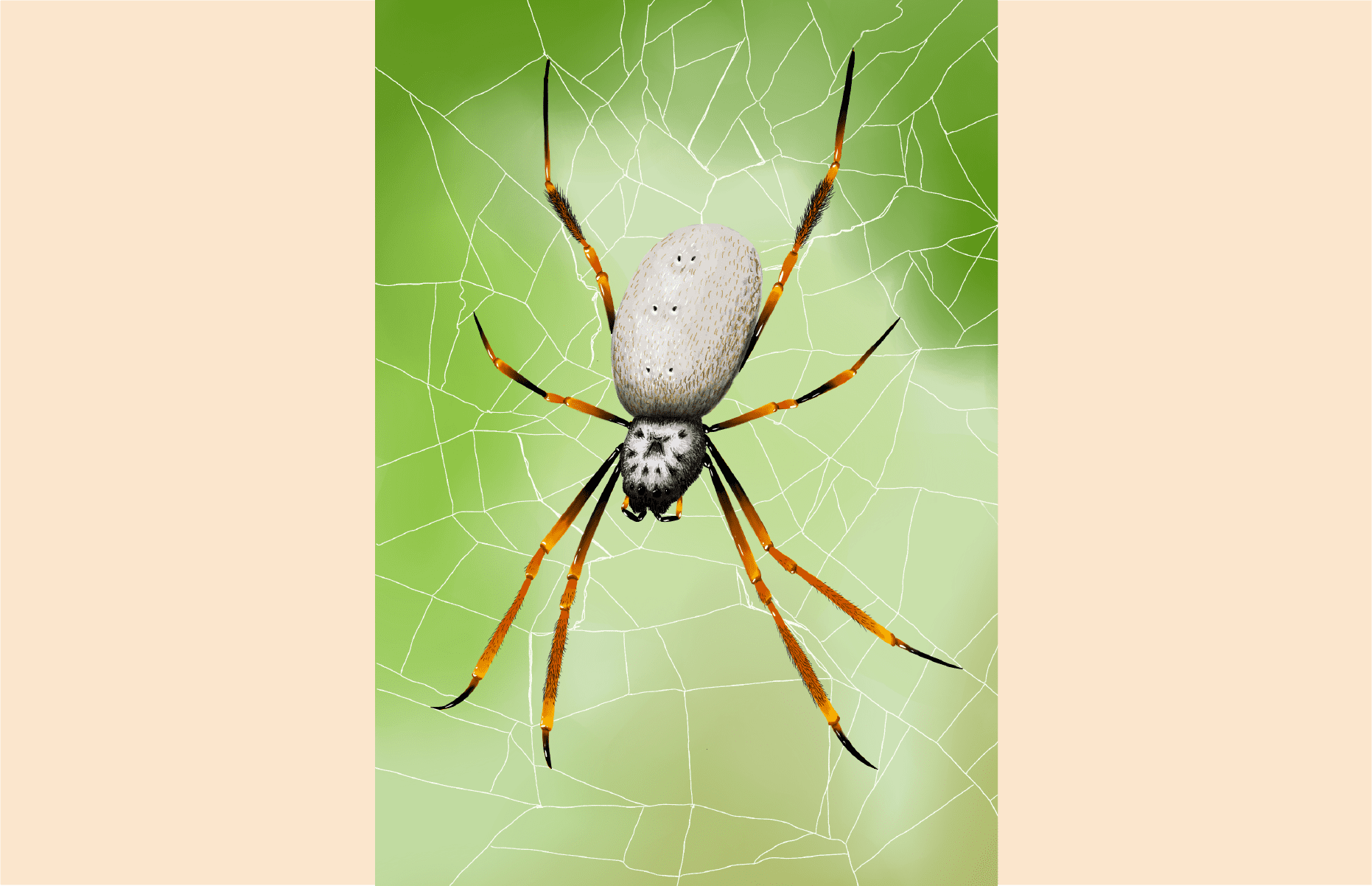

Similar stories have been playing out across Sydney. I’ve heard of gardens overrun by giant lattices of web, and seen firsthand the macabre displays of fly corpses, hollowed but still trapped in silken cocoons. As the bug guy in my friend groups, it often falls to me to identify the spider. So who exactly are we dealing with? The culprit is the golden orb weaver, Nephila plumpies. With black tipped fangs and blood-red legs, they’re freaky enough to look at. A quick google also throws up the phrases ‘sexual cannibalism’ and ‘risky mate search’, so their freakiness is more than skin deep. Among the largest of Sydney’s spiders, their huge webs have been known to trap small birds and bats, in an ecological interaction researchers consider ‘messed up’. And, judging from the number of ‘wtf is this’ texts I’m getting, it seems these giant spiders are spreading across the city with no end in sight.

This ironclad evidence is backed up by science, which points to an ongoing increase in their numbers. One crucial factor is the ‘urban heat island’ created by metropolitan areas: the dark, flat surfaces of buildings soak up more warmth than bushland, to the point that cities can be 10 °C hotter than surrounding forest. Being cold blooded, spiders rely on ambient heat to kickstart their metabolism, so they’re supercharged in city conditions. Research consequently shows that inner city Nephila grow faster and fatter than their wild counterparts. And as the globe continues to warm, we’ve reached a point where more and more female spiders can produce two egg clutches per season, doubling population growth.

It also doesn’t hurt that there’s more food around. Sydney’s lattice of parks and gardens seems to suit prey species, with urbanisation increasing the numbers of flies and wasps. Meanwhile, other spiders and predators struggle to survive in these human-altered environments, leaving the orb weavers with a wide open niche to dominate. In particular, as we clear vegetation, the increase in open space favours the spiders that can build webs large enough to span these gaps.

This is a classic tale in Anthropocene-era ecology: some animals win out, while others lose badly. Golden orb weavers are spreading because they were dealt a lucky hand that equips them well for life in modern Sydney. Plus, against this backdrop, we’ve seen years of favourable climatic conditions. The last El Nino dry period was in 2016, so every summer since then has been marked by considerable rainfall. I’m not sure if anyone noticed, but this last summer in particular had quite a few rainy days, resulting in lush plant growth and an explosion of insects including mosquitoes, flies and grasshoppers. In other words, more bottom-of-the-food chain fodder for orb weavers’ webs.

As with too many stories from contemporary natural science, these observations circle the drain of climate change. The spread of urban spiders, just like the increasing number of storms and heat waves, point to the tipping of vast scales somewhere out in nature. And, for every horrifying female spider that gets to secrete a second egg sac, another species’ breeding season is thrown into complete turmoil. The very same changes to El Nino – La Nina patterns have profound impacts across the Pacific, where they have started to threaten the Peruvian anchoveta industry, a bedrock of feed production for livestock worldwide. Around the world, ecosystems are rebalancing and simplifying, and each ascendant winner rises at the expense of countless losers, species not long for this world. So, next time you see a golden orb weaver on campus, you should be afraid. But maybe not for the reasons you think.