Artworks on campus are a rather ominous mainstay of our University; an omnipresent monolith we engage with inside every building, hallway, street and alcove. But with questions such as: ‘where does it come from?’, ‘who put it there?’ and ‘who owns it?’ mostly going unanswered, the influence art exerts over our academic and recreational environments remains uninterrogated.

In the context of a museum such as the Chau Chak Wing Museum (CCWM), it is a far less anonymous beast. A museum’s directors, curators, and staff are clearly the people who dictate which artworks get exhibited. As for the non-museums however, — academic spaces, lecture halls, libraries and tutorial rooms — well, who oversees them? Who hangs the portraits in the Edward Ford Building, who swaps-out the paintings in Fisher Library, who selects which sculptures stand on Eastern Avenue and beyond? Ultimately, who are the arbiters of our environment?

Ranging from contemporary First Nations sculptures to 19th century portraits of Vice Chancellors-past, whether you (quite literally) like it or not, the more than 8000 artworks controlled and displayed by the faceless University directly shape our relationship to campus.

It is markedly easy to disengage with the environments around us; and even easier to overlook their impact. But if art is anything, it is deeply political, deeply complex, and deeply influential. In short, it is worth paying attention to.

Art has an agenda, and so do the people who hang it. It ought to be consumed with active thought, and met with criticism.

Now, I’m not saying nobody pays attention to art on campus, but rather, I am attempting to demystify the forces that place art in front of our eyes, to delineate the history of art at the University of Sydney and to make the argument that students should get involved as they once did.

***

For as long as the University has been standing, it has been immersed in art. The University Art Collection, in fact, began in tandem with the University’s founding in 1850. Gargoyles, motifs and filigree have been carved into the sandstone of the Quadrangle, Great Hall and MacLaurin Hall since they were first built. Their ceiling carvings and relief sculptures of cherubs and coats of arms — or even the lion sculptures from 1927 at the Nicholson Gateway — were perhaps some of the first works of art on campus.

Clearly, art on campus has come a long and prolific way since then, with at least 24 major public sculptural works on campus display. Though there are many, many more if you care to find them.

It was once my hope to create a comprehensive list of every single University-owned artwork and its location on campus, though having proved to be even more wildly challenging than it sounds, I resorted to navigating the digital archives.

According to the digital collections search, there are only 349 artworks currently on display both in and outside of the CCWM. This raises the question, of the 8000 listed, where are the other 7,651? Moreover, it is astonishingly difficult to uncover which buildings these artworks are currently being displayed in. The advanced search function has 19 different variables to narrow your search including collection, material and artist. Though, disappointingly, none of the searchable functions include the current location of the artwork — the closest you can get is if it’s on display or not. Perhaps this is a deliberate choice to negate thievery, but I find it frustrating nonetheless.

Dreams of a colossal list dashed, I set my mind to the larger and more important questions such as, who controls the art within our learning environments, and why do students seemingly have no say in the matter?

To first understand the University’s approach to art on campus, I was fortunate enough to speak with Senior Curator for the University Art Collection, Ann Stephen — a renowned curator and author of seminal contemporary texts such as Modernism & Australia: Documents on Art, Design and Architecture. Importantly, the University Art Collection is a distinct entity to that of the Nicholson or Mcleay Collections (now also housed in the CCWM), as it boasts modern artworks and commissions, historic acquisitions, donations, and the art archive of the University.

To elucidate the murky process through which art enters the University’s collections, I asked Stephen about the acquisition process. She explained that “We don’t have an acquisitions budget as such, which is disappointing, but that’s the situation.”

“What has been the case in recent years is that when new buildings are built, part of the requirement of Sydney Council is a certain amount is invested in art or landscaping. That has allowed us to commission some new work.”

Stephen elaborated that when a new building arises on campus, a committee called the Art in the Public Realm Committee selects an artist “in a competitive way” to commission a work specifically for that building. Consisting of eight members, including Stephen herself as Senior Curator, the Committee includes relevant academics, the Director of Museums, campus infrastructure services, and the University’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community.

A 2018 strategy document reveals the Committee’s process of obtaining and situating a new artwork on campus is as follows: a new building project is begun, the client project briefing begins, concept development occurs, the concept is reviewed, the design undergoes development, and finally it is documented and delivered to location.

The document further explains the goals of the committee, namely to “create and sustain a university in which, for the benefit of Australia and the wider world, the brightest researchers and the most promising students, whatever their social or cultural background, can thrive and realise their potential.” This admittedly sounds very nice, but only pushed me to further wonder why students do not play a larger role in the curation of campus art. Rather, we are left to be the receivers of the art, rather than the arbiters.

The second, and final, time students are mentioned in the document is as “audiences and stakeholders” — alongside visitors and tourists. Remember, this is for art outside the University’s museums, in student spaces. I would argue that we are not the audience, but the participants.

Asking further about the commissions process and other avenues through which art might come into the University, Stephen explained to me that of the approximately 11,000 works in the collection (notably more than what the website suggests) the “largest way artworks come into the University is actually donation.”

To truly scrutinise who exactly is donating these works, in lieu of a lovely long list, you’d have to look up all 11,000 individually on the digital archive — an impractical task, which only furthers the sense of opacity I get from the collection.

Desperate to uncover the curatorial processes for individual non-museum buildings on campus, I asked Stephen about two of the most well-known buildings on Eastern Avenue: F23 and Fisher Library

The Administrative building, F23, because it “was seen as a very public facing building” was in fact curated by an external art curator, Vivienne Webb. Similarly, Fisher Library is regarded as a “high usage building” and therefore it is “regarded as very important to show [the University Art] collection” there. Though it seems Fisher has a greater level of autonomy than the corporate F23, Stephen explained that the SCA has mounted several student exhibitions within Fisher, and that the staff themselves also conduct their own exhibitions downstairs in their Rare Books collections. Further, from time to time, librarians request new artworks from the University Collection, and seek advice from university curators such as Stephen.

Prying further into the smaller academic and lecture buildings on campus, I was anguished to know who hangs the seemingly random artworks in backwater tutorial rooms, Stephen tells me that there is a “subtle distinction between the Art Collection and things described as ‘assets’.”

“Something that isn’t in our collection, but say, a staff member has commissioned, we might call that an asset. And we don’t have the same level of conditions applying to that,” says Stephen.

This appears to suggest that many of the artworks in small academic buildings and hallways may not be in the possession or in control of the University Collection, nor its curators. Rather, they may be controlled and displayed by the academics, deans and professors who reside in them. Unfortunately, I couldn’t nail down a definitive answer on this, however, it is noteworthy that uncovering the provenance of campus artworks en masse has been near impossible. What could they be hiding? Definitely not portraits of old, white men — we already know about those.

An academic who works in the Brennan MacCallum Building told Honi that the artworks in their building “could definitely just be there at the discretion of staff” and confirmed that there is no official budget for art displayed in academic hallways.

Though admittedly having “never heard anything official about it”, the academic explained that “Schools make choices about buildings the Faculty/Uni would have no clue about”. Beside having to pass a “code of conduct check”, the academic from the School of Gender and Cultural Studies communicated to Honi that — unless they were planning to drill a hole — they “wouldn’t ask the School Manager for permission” to display an artwork.

From this, one can conclude that both the University Art Collection and University Faculties, Schools and Departments all have a stake in campus artworks. Unfortunately, this only muddies the waters of who has actually placed any given artwork — seemingly, it could have been any member of staff across the last 172 years.

***

Unable to demystify the present, I turned to the past and delved into the archives, hoping to find some answers about what art used to be like on campus way back when.

As it turns out, attitudes toward decolonising art, criticising its politics, and investigating what it means to us as young people has been embedded within the USyd zeitgeist for decades. One Honi article from 1975 reviewing an exhibition from the Art Gallery of New South Wales exclaims: “I left feeling absolutely disgusted with the values of art as they were displayed by the exhibition,” continuing to say that “It is not particularly surprising there are no women artists represented”. This review is indicative of the attitude toward art among the student left on campus way back in ‘75 — highly critical.

Another article from a 1989 Honi, reviewing an exhibition of work by USyd students out of the Tin Sheds describes one of the works as attempting to “vandalise, even terrorise, masculine academic production.” The review links the political landscapes of campus in the 80s, and even still today, as being rife with sexism.

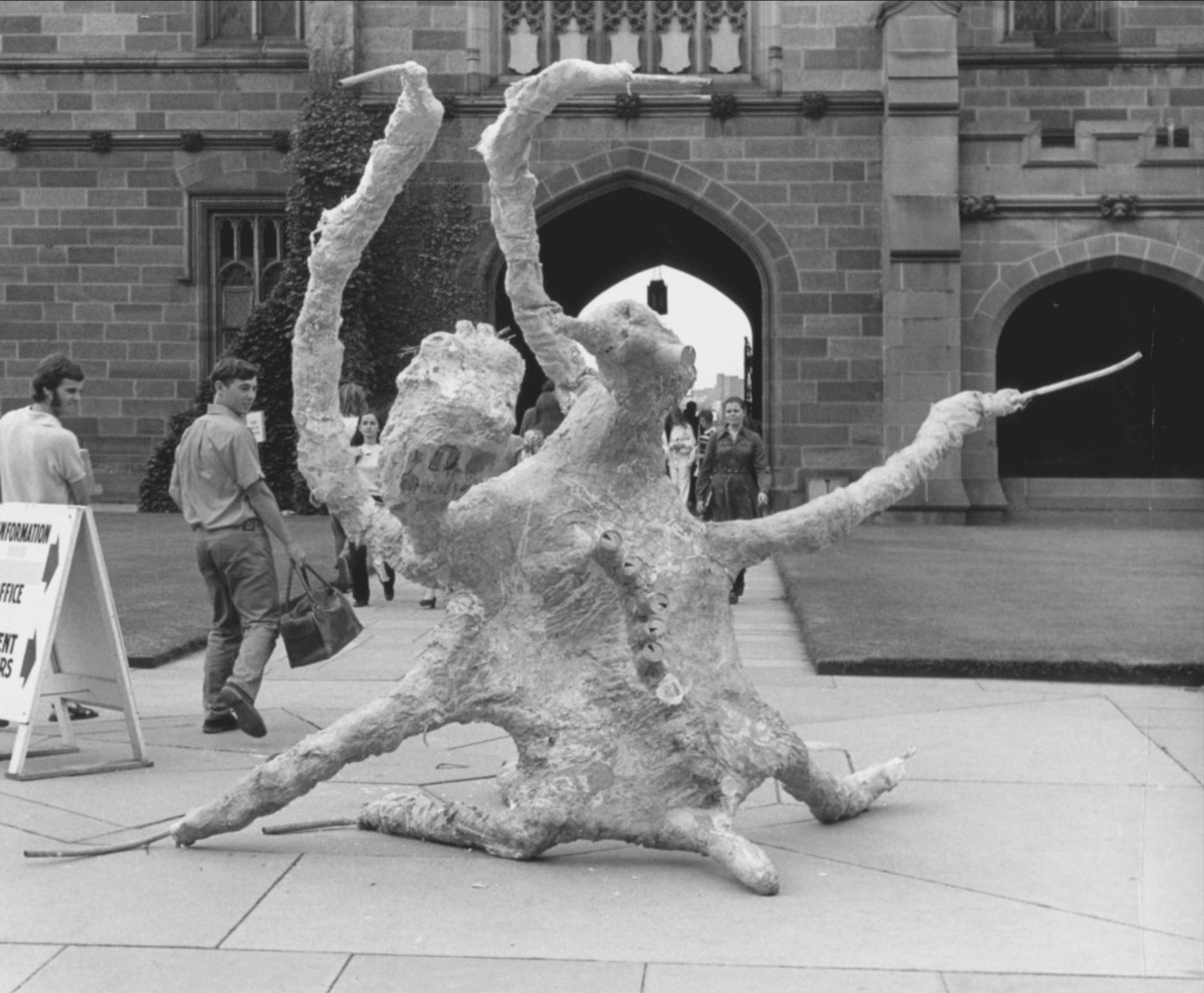

An archival photograph from Orientation Week 1971 shows an amorphous sculptural figure, perhaps made out of papier mache, in the middle of the Quadrangle’s intersecting pathways (see figure 4). According to the archives, it’s entitled APITHIE — no artist is listed, nor any further attribution other than its apathetic title. I don’t know what it is, but I enjoy it immensely. To me, it represents what students ought to be doing on our campus, that is: making it our own again and reclaiming autocratic spaces through art.

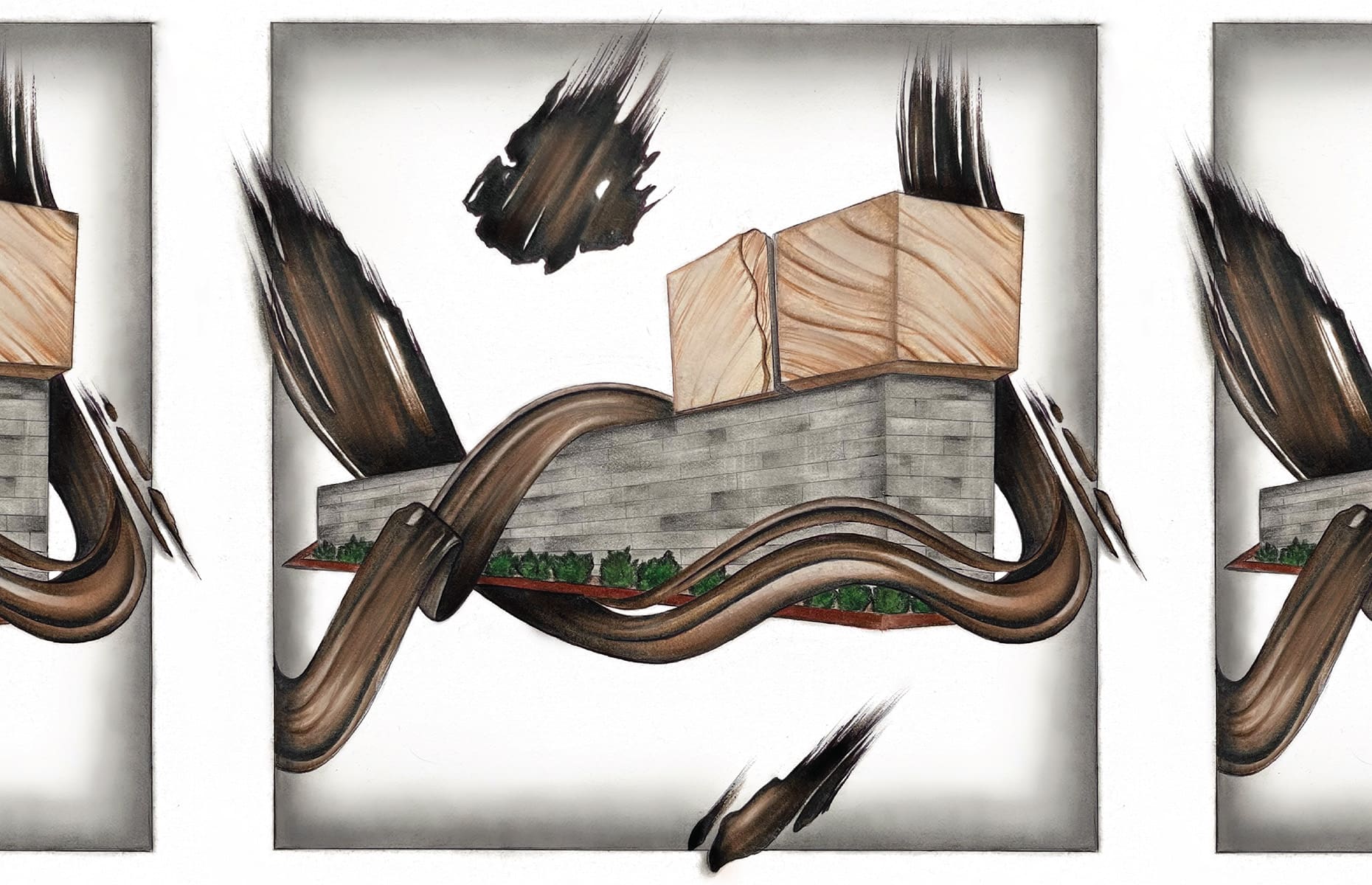

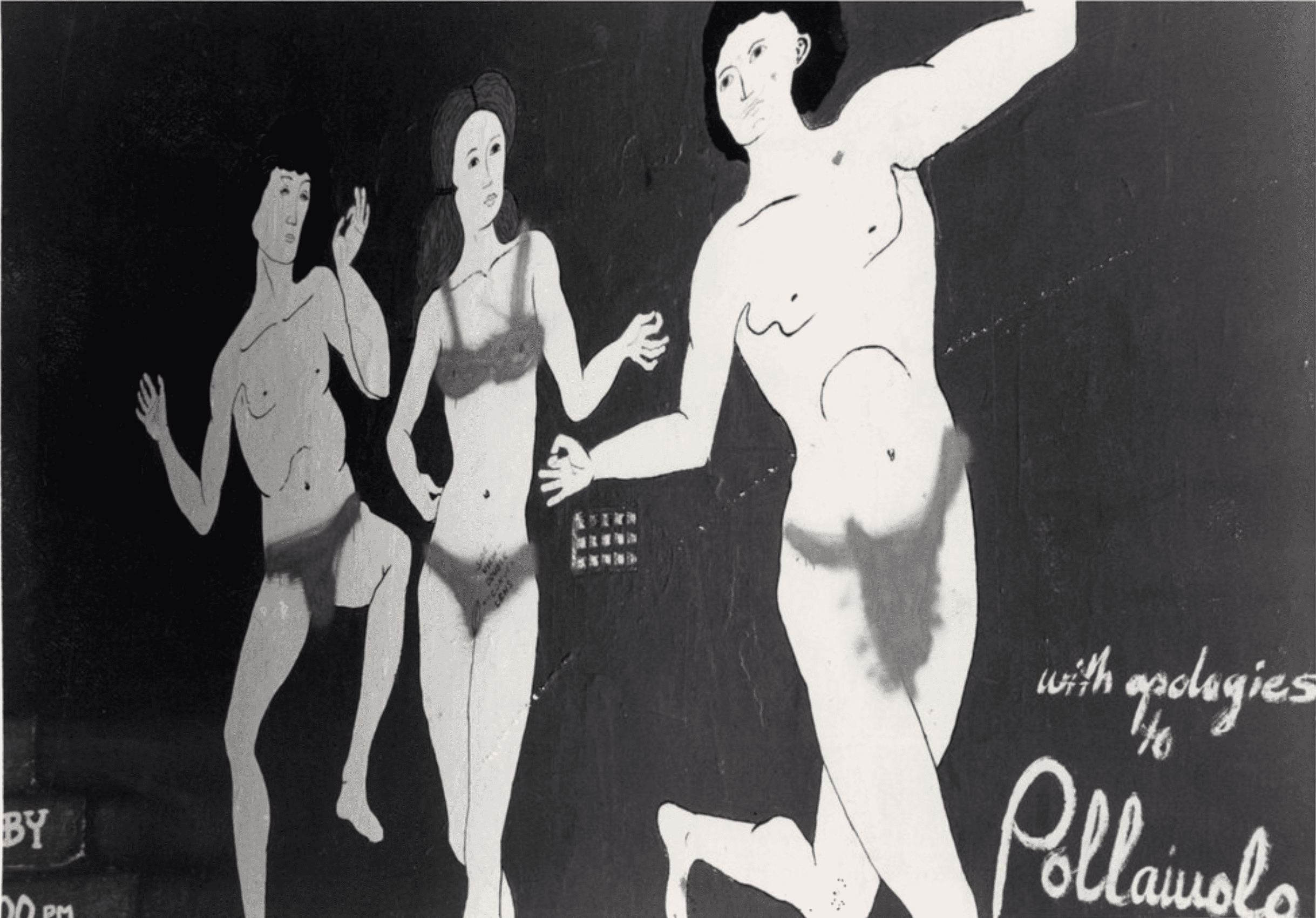

A salacious and vandalous example of this reclamation from 1979 in the Badham Building Tunnel, now colloquially known as the Graffiti Tunnel, is rather elucidative of the ‘70s campus climate. The photo in question is captioned by the University archives as: “The yearly painting of the tunnel beside Badham building by The Renaissance Players of three nude dancers was defaced” (see figure 1). The Renaissance Players were a student-band on campus with an eye for Renaissance art, leaving a note on their mural which reads “With apologies to Pollaiuolo.” Pollaiuolo was an Italian renaissance painter, and with a little art-historical digging, I found that their painting is a likely recreation of his fresco Dancing Nudes from c.1465. Which is, indeed, just as naked as their modernised rendition was.

As any dutiful USyd student would know, the Graffiti Tunnel is a site of constant creation and destruction; though in this case, it was a site of censorship as the naked figures were spray painted over. Naturally, they were rapidly restored (see figure 2).

There is something deeply gratifying about knowing that the tunnel has always been a site of artistic discourse and political dissent amongst students. It seems, in this regard, not much has changed — though I can’t say I’ve ever seen a naked renaissance-esque painting in there before.

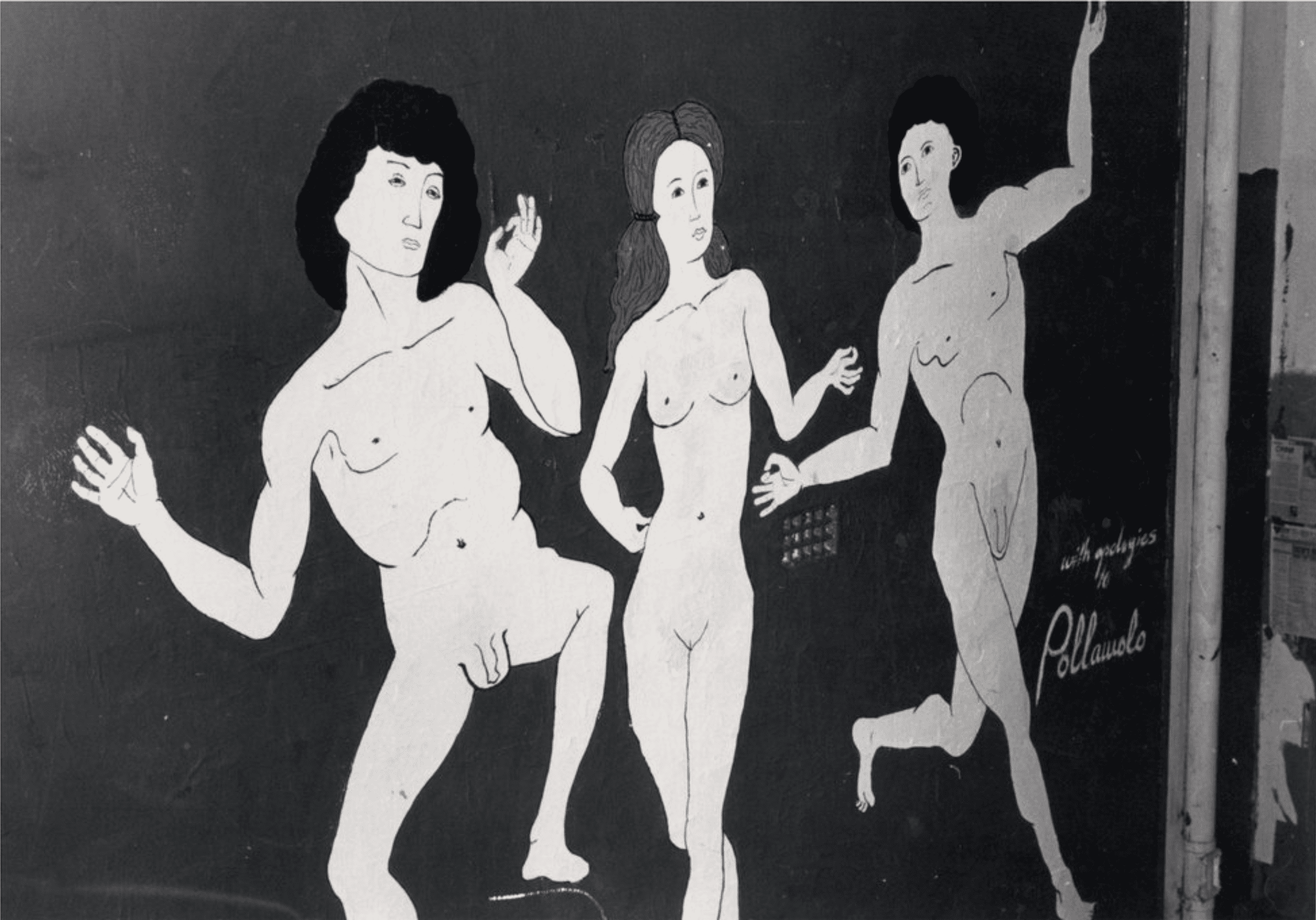

Furthermore, according to a 1976 Honi, there was an exhibition space in level five of the Wentworth Building (see figure 3) showcasing women artists of USyd. The ‘McDonald Gallery’ returns no further results in the archives or online. Remaining somewhat of a mystery, it nonetheless stands as another example of the artistic aspects of student life we’ve left behind and the artistically political campus we’ve lost.

So, where did we lose it? Without discrediting the work of campus institutions such as Verge Gallery — a contemporary art exhibition space supported by the USU — one cannot help but feel like the vivacious, political activity of student-artists on campus has been lost to time; the once central aspect of university life seems to have all but disappeared outside coursework settings.

The formerly autonomous art-space called the Tin Sheds, officially integrated into the University in 2004. Despite becoming less of a ramshackle studio, with new purpose-built spaces and galleries, the integration process has erased the space’s autonomy from the University. Potentially, this caused the stark decline in student-lead political, artistic activity in our present-day campus.

Though, there are hopes that the reintegration of Sydney College of the Arts (SCA) into the Camperdown campus, along with the relatively new Chau Chak Wing Museum, will revitalise student-led artistic activity at USyd. This comes alongside events of Sydney College of the Arts Student Society (SCASS), founded in 1990, hopefully making a radical appearance on main campus for the first time.

Stephen told Honi that having the SCA move onto campus provides an important “combination of young artists, as well as access to art for all students in a way that we never ever had before,” emphasising that it is “far more complex and rich than just having the portraits in the Great Hall.”

Speaking of the Quadrangle, I asked Stephen about these portraits and their distinctive lack of diversity, pointing out their overwhelming majority of white, male academics.

“I agree with you, the halls are surrounded by dead white men. We are super aware of that, and attempt to change it,” said Stephen, pointing to two 2017 portrait commissions by artist Celeste Chandler that are now situated in Mclaurin Hall: one of Professor Nalini Joshi and another of Professor Margaret Harris.

In recent decades, there has been a significant push through commissioned works to increase the number of Indigenous and First Nations artworks on campus. Speaking to this renewed effort, Stephen explained that whenever they receive a request for an artwork they “respond by looking widely, giving a particular focus to women and to Indigenous artists — It’s pretty important to us.”

As noted in a letter to the Honi editors of 1990, there has been a distinct lack of First Nations art on University grounds for several decades, if not for the entirety of the University’s life. As part of an initiative called the Koori Art on Campus Fund, the letter-writer Patricia Rovik called out the lack of First Nations and Koori art on campus in the 90s and prior.

The letter opens: “Dear Honi readers, Had you noticed that there is very little Aboriginal art on display in the student-frequented areas of campus?”

I think it is perhaps likely that many had not noticed. Though today, one only has to look so far as the major City Road entrance of USyd to see Spine (2018) by Indigenous artist of the Bidjara, Garingal and Ghungalu peoples, Dale Harding, – the inspiration for this week’s Honi cover.

The unmissable work is a monolith on campus, representative of Australia’s geographical great divide, but also our colonial one. Working in response to the sandstone buildings of USyd and the sandstone embedded in Eora land, Harding’s work presents the two sandstone blocks “side-by-side, with no hierarchy.”

Another important modern campus artwork is Judy Watson’s juguma (2020), situated outside the new Susan Wakil Health Building. As one of the most recent art commissions on campus, Watson’s work is described as an “extension of the building” that celebrates the customs of Indigenous peoples in its large-scale metallic form — representing a dillybag, traditionally woven from plant fibres.

There are many more artworks to be found on campus than the few I’ve mentioned here; whether they’re lonely gargoyles growing dewy with moss, or contemporary works making great strides, it’s all there ready to be seen, enjoyed, and critiqued by you. So get out there, and get ready to look.

***

In the end, I wasn’t able to uncover who truly moves around the portraits in our hallowed halls or which forces decide how long that painting from over 50 years ago should stay hanging.

However, I did discover that the line between where the CCWM ends and the art in our student-spaces begins, is far blurrier than I initially expected. Aside from private ‘assets’ not owned by the University Art Collection, “All artwork on campus is our responsibility” according to Stephen.

Personally, I would like to see more student-created, student-curated works like APITHIE appear across campus — even if security comes to take them down.

Students deserve to see the political works of their contemporaries and predecessors hanging in their lecture buildings and study spaces: the artworks of political resistance created during the Anti-Vietnam War protests of the 60s and 70s, artworks of protest from the Cold War era, the radical and defiant Feminist screen-prints of the 80s Tin Sheds, and the contemporary beyond.

The artistic legacy of students should be upheld, championed as a bastion for posterity — showing what can be collectively achieved by students, through art.

Artistic sit-ins, snap actions of creation on Eastern Avenue, and art-postering campus walls are all forms of direct artistic and political action that students of USyd once took, so why not again?

Who wants to start an Autonomous Art Collective?