Silent and serene. You are engulfed by a room made only of mirrors. Spotted white and red amorphous blobs litter the ground, giving the illusion that you are amongst a bountiful field of phallic fungi. The reflective surfaces echo your own astonished expression. You are completely alone, yet surrounded by a multitude of selves. You reach for your phone and take a picture; in this regard, you are not alone. You are among the one million people who have snapped and posted a quick self-portrait in one of Yayoi Kusama’s mirror rooms.

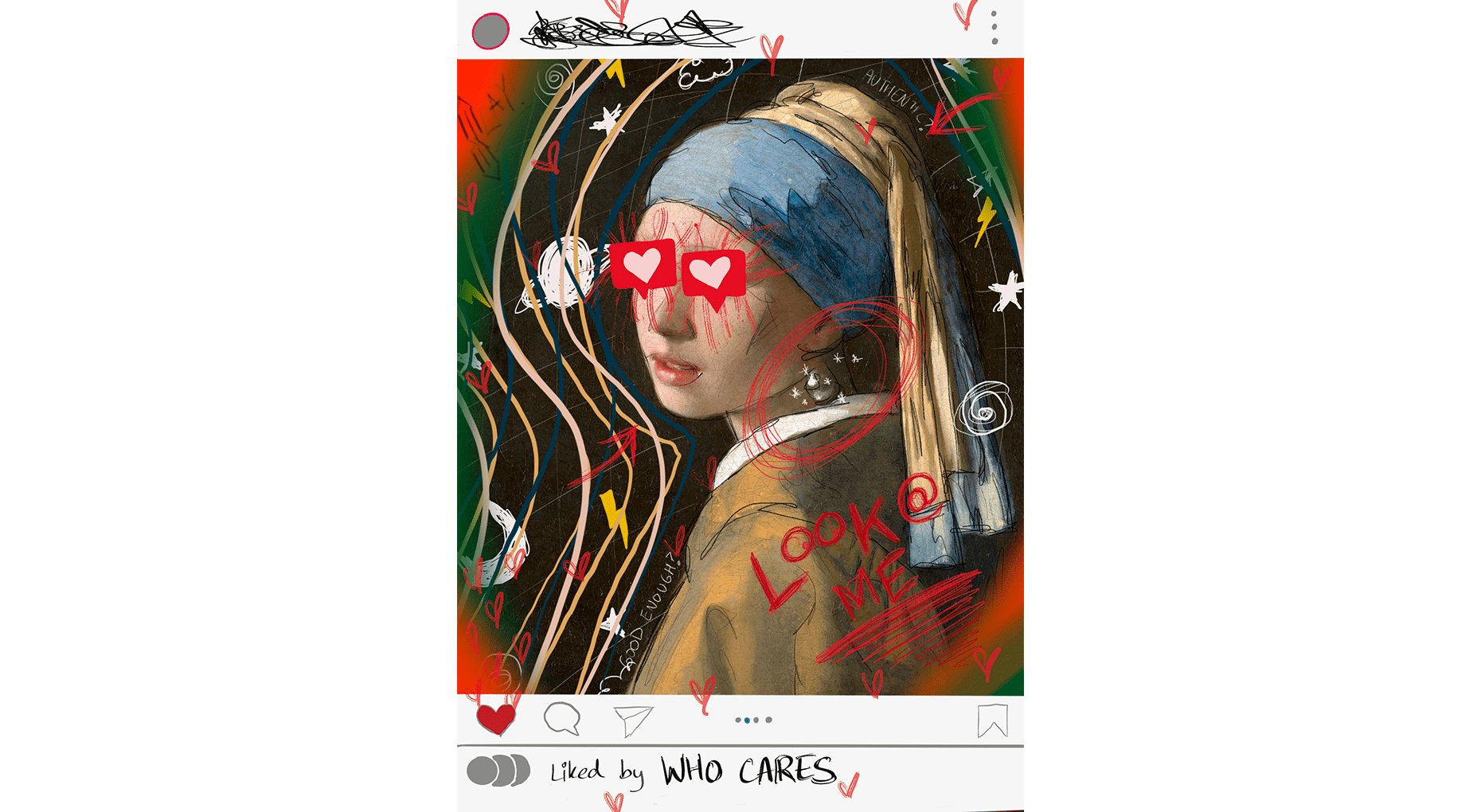

Attracting thousands of visitors to galleries around the world, Kusama’s acclaimed ‘mirror rooms’ epitomise dialogical art – art that engages its viewers in a conversation, often through direct participation. In hopes of democratising art and enticing a larger audience, galleries have shifted their focus to social media exposure. With viral posts drawing in troves of gallery visitors, it is unclear whether the strategy promotes engagement with the broader art world or just encourages fun photos.

Demand for art that dissolved the barrier between artwork and viewer emerged during the mid-twentieth century. Participatory and installation art answered this call, allowing audiences to become co-authors and collaborators. Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece (1964) – which invited viewers to cut pieces off Ono’s outfit as she sat – and Marcel Duchamp’s Mile of String (1942) are early examples of works that prioritised the viewer’s experience and engagement in their presentation. Since then, the movement has inspired

more modern immersive artworks, ones that earn their success through their photogenicity.

This is most recently evident in exhibitions like van Gogh Alive, which has flooded social media feeds since the installation began touring in cities around the world in 2020. Cavernous rooms were decked out with projections of Vincent van Gogh’s prettiest artworks, yet they were confined to twenty-four-hour story posts and Instagram feeds. James Turrell’s 2013 installation Aten Reign illuminated the floors of the iconic Guggenheim in New York City, bathing the building in bold hues. He asked that no photos be taken as it would detract from the experience, yet despite this, the hashtag ‘#atenreign’ has over 500 posts attributed to it.

With the art world’s infiltration of social media, we are left with the question of whether these captivating pieces create meaningful dialogue or simply decorate instagram feeds. To better understand the democratisation of art and the role platforms play in educating, Honi spoke to artist and lecturer at The Sydney College of the Arts, Dr Alex Gawronski.

Gawronski described social media’s relationship with art as inescapable: “It’s largely connected to things like promotion, it’s connected to the informational – which is basically just the supplying of information about things, which I think is a very different thing [to education],” he said.

Gawronski emphasised the distinction between the availability of information as opposed to the act of educating. “I think in terms of democratisation, it just comes down to education and curiosity,” Gawronski said.

“I think the tendency within Australian culture is to want to disinterest [students] – contemporary art in particular as being pretentious is really culturally inscribed.”

“It’s a great way to access where certain things are, but education is a very active space, it’s a two way, multiple kind of communication. It’s not information. Information is very one way.”

He also emphasised that the immediate visual appeal of an artwork dictates most of its engagement. Accordingly, the concept of Instagrammable exhibitions has shaped curatorial practices in response.

“Whatever is most vibrant or pretty is probably going to garner a lot more attention than things that don’t ‘look like art’, right?”

“I think going to see work in person is a very different thing depending on the work. I think the tendency will always be to [choose] things which read well two dimensionally.”

Touching briefly on the kind of art social media tends to favour, Gawronski explained that “if you work in sort of more subtle [ways], if you’re working more [in] conceptual ways where it’s quasi-visual, I mean, Instagram doesn’t really lend itself to that sort of platform because the focus is not on the visual really.”

However, Gawronski also made sure to emphasise the positive element of social media for artists. “It’s very easy to find out things that are going on,” he said, adding “it’s good for the institution. It gives a lot of exposure, more exposure to the artists.”

Yet, this desire for exposure emphasises the aesthetic, rather than conceptual quality of art. Alluring artworks, digitised and shared, may be bringing people into the gallery, but what is making them stay? In celebrating what is beautiful at first glance we may overlook that which takes a little longer to appreciate. Nevertheless, I think it is time we revere art for all of its qualities, photogenic or not.