Not a war fought with guns, explosives or a real enemy, but one fought against intangible forces — time, geography, bureaucracy, and culture. Against these adversaries, Sydney is faced with unique difficulties in its attempts to create a more livable city.

Stretching 70 kilometres from east to west, with a population of only 5 million, Sydney is expansive. In comparison, New York City is home to over 8 million people in a city 90 per cent smaller. Sydney’s sprawl creates an overwhelming vastness which has become the enemy of our public transport — transport that facilitates access to work, social services, and recreation.

With the advent of the motorcar, the scope of residential occupation in the Sydney Basin has expanded. Communities branched out from key road and rail corridors into progressively more isolated areas, creating low-density settlements along with new opportunities for industrial and vocational work in Western Sydney.

The car was believed to provide a remedy to the spatial issues of the area, but with commute times now averaging 71 minutes a day for the average Sydneysider — and the global push towards the use of mass public transit instead of private vehicles — the notion that the car is the solution is increasingly archaic.

Currently, there are two new Sydney Metro lines under construction which branch into the Western suburbs south of the Parramatta River. Both departing from the inner city, one line will service routes to Parramatta, while the other will go southwest to Bankstown. The purpose of the current Metro is to relieve pressure on the heavy rail network during peak times, and to support “employment growth” according to the NSW Government.

However, the design and scope of Sydney Metro is critically flawed. Metro railway cars are built for short distance, inner city travel: there are no bathrooms, limited seating, and often become overcrowded. Anyone who’s ridden on metro rail overseas knows how uncomfortable the choking crowds and constant standing can get after a short while. So why is there a single line extending from Rouse Hill through the city to Bankstown?

To add to this mess, the state government has repeatedly doubled down on the choice to bore tunnels that are only big enough for single-deck metro cars, excluding the possibility of Sydney’s regular railcars ever operating on those lines. This isn’t planning for the future, this is a short-sighted, ill-conceived plan with inherently little room to improve once implemented.

Covering a vast swathe of land, Sydney’s lack of transport to underserved areas cannot and is not being improved by a Metro system that should be relegated to the inner city. Western Sydney, and Greater Sydney itself, urgently needs its own dedicated heavy rail and bus upgrades to accommodate the projected one million new residents by 2041.

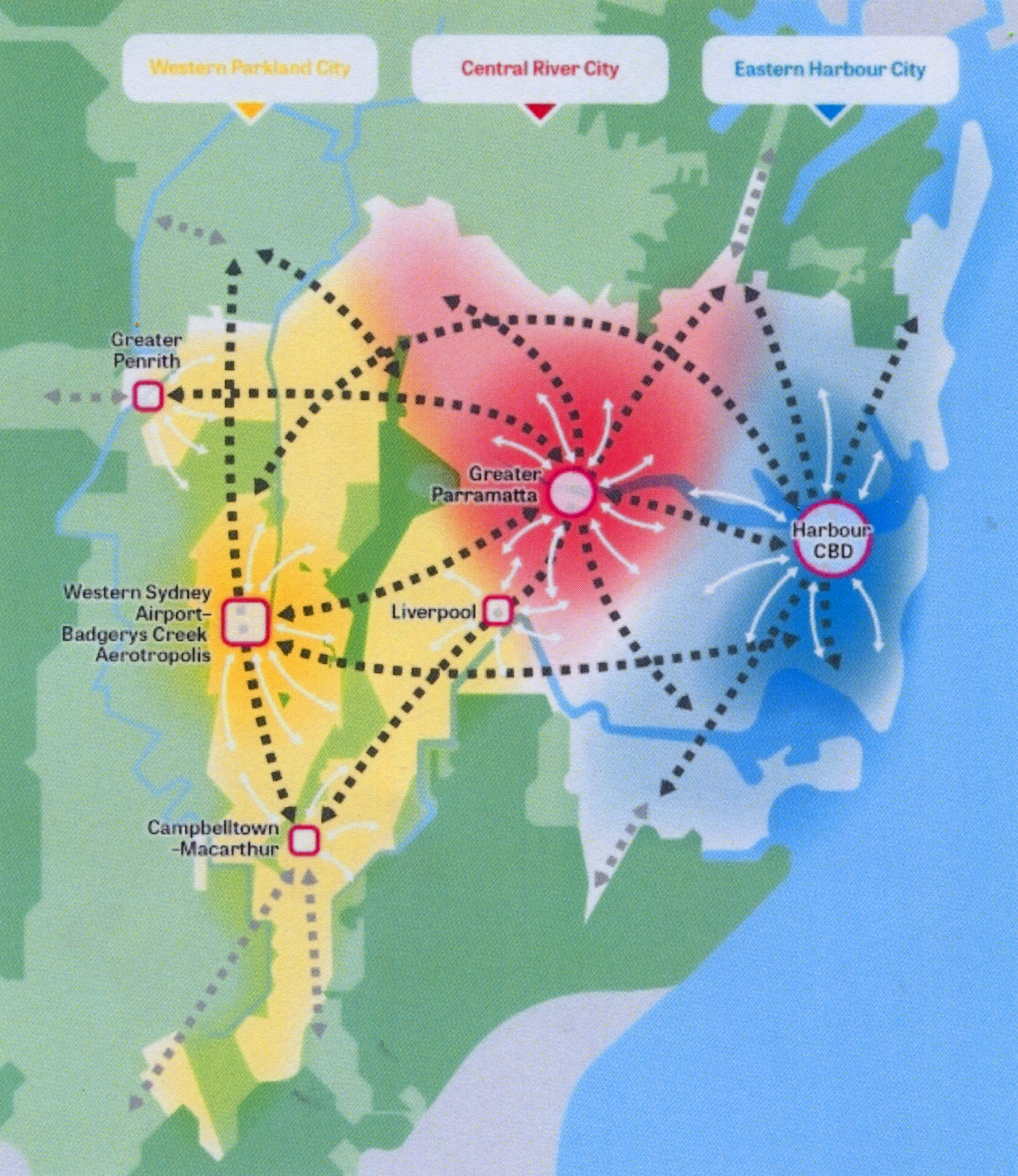

A way of subdividing the looming difficulties of connecting all of Sydney is to reject the idea that the CBD is the heart of the city with a gigantic western flank trailing it. Instead, the independent Greater Cities Commission, established by an act of parliament in 2015, imagines three defined cities in Greater Sydney — the Eastern Harbour City (the current CBD), the Central River City (Greater Parramatta), and the Western Parkland City (Badgerys Creek and Penrith) — splitting the city into thirds from east to west.

By “guiding private sector investment”, the Commission aims to encourage the economic and infrastructural growth of the three cities, creating more job opportunities near these centres. In doing so, the logistical nightmare of connecting all of Sydney is broken into bite-sized chunks; aspiring to have all Sydneysiders within 30 minutes transport of their work, public services, and recreation.

Bolstering lofty claims and utopic jargon, the plan isn’t without criticism. Associate Professor Glen Searle from USyd and Professor Emeritus Kevin O’Connor at the University of Melbourne argue that prioritising fast rail connections to the new ‘Aerotropolis’ near Badgerys Creek hinders the development of a better rail network to Parramatta that could result in an economic and cultural challenger to the inner city’s hegemony.

In their article, they contend that “there is little attempt [by the Greater Cities Commission] to help tackle the housing affordability crisis,” reflecting the limited attempts of new developments to make meaningful contributions to affordable housing growth. However, Searle doesn’t dismiss the paper entirely, saying that “a bold but arguably flawed vision is to be welcomed for broadening the discourse about options for Sydney’s future.”

Another significant planning issue is urban heat: the Western Parkland City sits in the hottest place in the Sydney basin. On one Saturday in early 2020, Penrith became the hottest place on Earth at 48.9 degrees Celsius, with Badgerys Creek itself ranking fourth globally. The sunbaked stretches of the western Cumberland Plain are inherently hotter than Sydney’s coastal east, and climate change will only worsen this. However, much of the blame can be pinned on the urban design of Western Sydney.

Sub-divisions of black-roofed, bitumen-lined housing estates with little to no green space all promote the absorption of heat, bringing our battle for the future of Sydney’s urbanism to its most dire front. With parts of Western Sydney projected to become abandoned within the next 20 to 30 years due to extreme heat, this is no longer a fight between the common good and the government — the way we build our suburbs is a decision between life and death.

The option that would result in the best outcomes would be the densification of the suburbs. If many people moved into tall complexes, more space could be allocated to vegetation and shade, actively promoting the reflection of heat and resulting in a cooler local climate. Denser urban centres also facilitate simpler public transport network design, to service more people in a smaller area.

However, like the Greater Cities Commission, that is an idealistic vision completely at odds with reality. To many who live in the low-density suburbs, that is the definition of the Great Australian Dream: a family, a car, a house, a quiet neighbourhood. Knowing this, it’s unlikely for MPs to even remotely support the idea of densifying the suburbs.

Instead, using reflective and lighter colours during housing development would alleviate heat absorption, including the allocation of more shaded areas on street curbs and more dedicated green spaces. However, the additional space required for vegetation would get serious pushback from developers. If the state government’s plan for a ban on dark roofs was abandoned due to pressure from real estate magnates, a push for mandatory shade cover will be even more challenging.

If these hypothetical shade and vegetation regulations were implemented, the lower housing density would spread communities further apart, making reliable public transport even more impractical. We can dream of a compromise, but the suburbs are simply too lucrative; implementation of policy is too often directly or indirectly in the hands of developers.

That’s the common thread — the combined failure of the public and private sector to make key decisions for Sydney’s future. Whether the government has completely lost touch or their partnerships with developers and businesses derail any good intentions, winning any battles for the common good is a slow, uphill fight.