When I was 15, ‘The Perks of Being a Wallflower’ was my favourite movie. It embodied everything I romanticised about teenagehood. Existential questioning, making rash decisions, falling in love for the first time. I wanted nothing more than that experience. I was determined to make it happen.

When I was 16, I fell into a period of deep sadness for the first time. I didn’t understand what was happening, and I had no idea how to fix it. I was surrounded by people who seemed to have suddenly grown up. I mourned my childhood but yearned for adulthood.

I would watch coming-of-age films on repeat. I knew the moment I wanted; the one where the boy stands outside the girl’s window with a boombox. After months of internal frustration and panic, I realised I didn’t want it to be a boy. I wanted it to be a girl.

But those dreams didn’t fit into the narrative of my life. The one where I replicated my own family, and had the perfect family. And they certainly didn’t fit into my preconceived idea of my final years of high school. That perfect coming-of-age story I was supposed to have was snatched away from me. This wasn’t what was supposed to happen. My collection of coming-of-age movies didn’t prepare me for this.

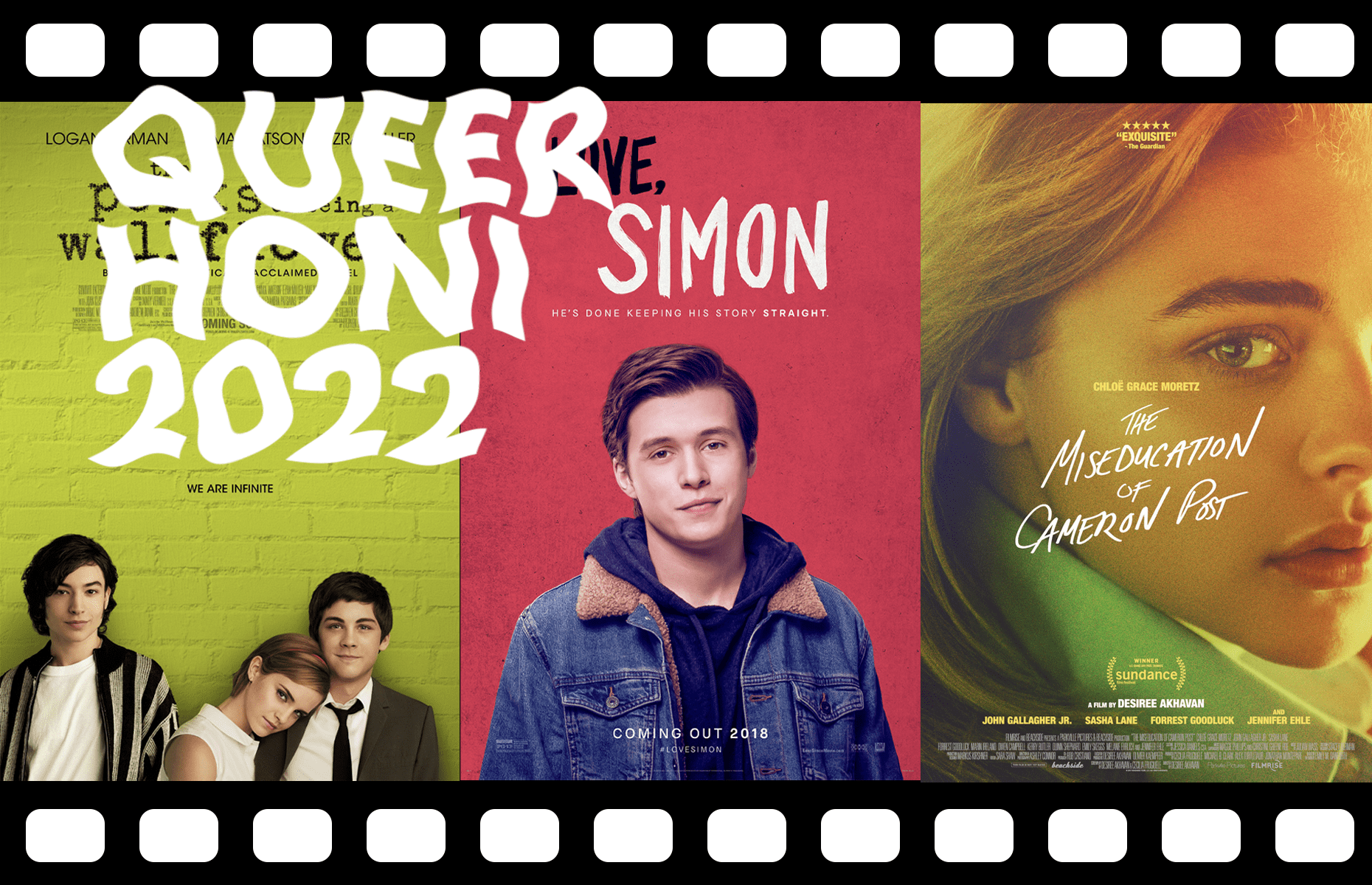

When I was 17, it was the year of queer film. ‘Love Simon’, ‘Disobedience’, and ‘’The Miseducation of Cameron Post’ were the first time I’d seen queerness so explicitly represented on screen. I felt inspired. I told my closest friends about my (at the time, bi)sexuality. However, I was still incredibly insecure. I kept my cards close to my chest.

When I was 18, I did so many dumb things. I drank too much and tried to replicate all the moments I’d seen in movies. I was always confused when I woke up the next morning and tried to forget about random hookups. But this was what it was supposed to be, wasn’t it? I was bi. I was supposed to enjoy this.

Enter: University. My eyes were newly pried open, and I felt like a goldfish in a shark tank. I was desperate to fit in. I dyed my hair every colour of the rainbow, thinking it would make me look more queer. I ordered a Hayley Kiyoko t-shirt and paraded around in it at debating tournaments. I developed a life-engulfing crush. I was a reckless chameleon. I became an unrecognisable version of my past self. Yet I didn’t understand why I didn’t feel the sense of euphoria you were meant to after a year of supposed ‘coming-of-age’ moments. I didn’t feel a sense of personal growth. I felt that same inner turmoil from when I was 16.

When I was 19, I finally realised that I was gay, not bi. At first, I mourned the potential to have a typical nuclear family. I mourned the fact I’d have to tell people all over again. But mainly, I felt relieved. Relieved that I finally understood myself.

When I was 20, I had my heart broken for the first time. Then, I came of age. Again. This time, properly.

Before, I always compared my experiences to the heteronormative society I had grown up within. I was always disappointed.

Then, I learnt to push those expectations to the back of my mind. Now, I can usually ignore them.

Before, I grieved my lack of a typical coming-of-age experience.

Then, I realised the merits in my own coming-of-age experiences, regardless of their normativity.

I’m now 21, and I realise the problems with our conception of the coming-of-age experience.

The concept of development milestones is rooted in compulsory heterosexuality. The constrictive singularity of the books we read, and the films we watch. The expectation to have a crush. The constructs surrounding virginity. Coming-of-age is a uniquely individual experience.

I hope the formula for coming-of-age becomes more and more diluted. I’m quietly confident that this is becoming the case. When I talk to high schoolers that I coach, they are increasingly open and excited about queerness and identity. Still, we need to diversify the media consumed at the high school level, and recognise the limitations in that media we continually come back to. We need teachers to foster conversations around identity, rather than skirt around them. Most importantly, there needs to be a recognition that these traditional narratives are, at best, unrealistic, and at worst, intoxicating.

‘The Perks of Being a Wallflower’ will always hold a special nostalgia for me. It represents what I wanted, what I’ve had, and what’s to come.

“I know there are people who forget what it’s like to be sixteen when they turn seventeen. I know these will all be stories someday, and our pictures will become old photographs. But right now, these moments are not stories. And in this moment, I swear, we are infinite.”

– The Perks of Being a Wallflower