I don’t relate to angels because they’re almost always white-skinned, slender and have a voice so irritatingly gentle that it bores me to death. So when my mother calls me an angel, I ask her what it is like to have birthed a perennially angry angel, who finds home in dissent and is quite a killjoy. “It’s alright, actually really fun,” she answers with her fractured smile.

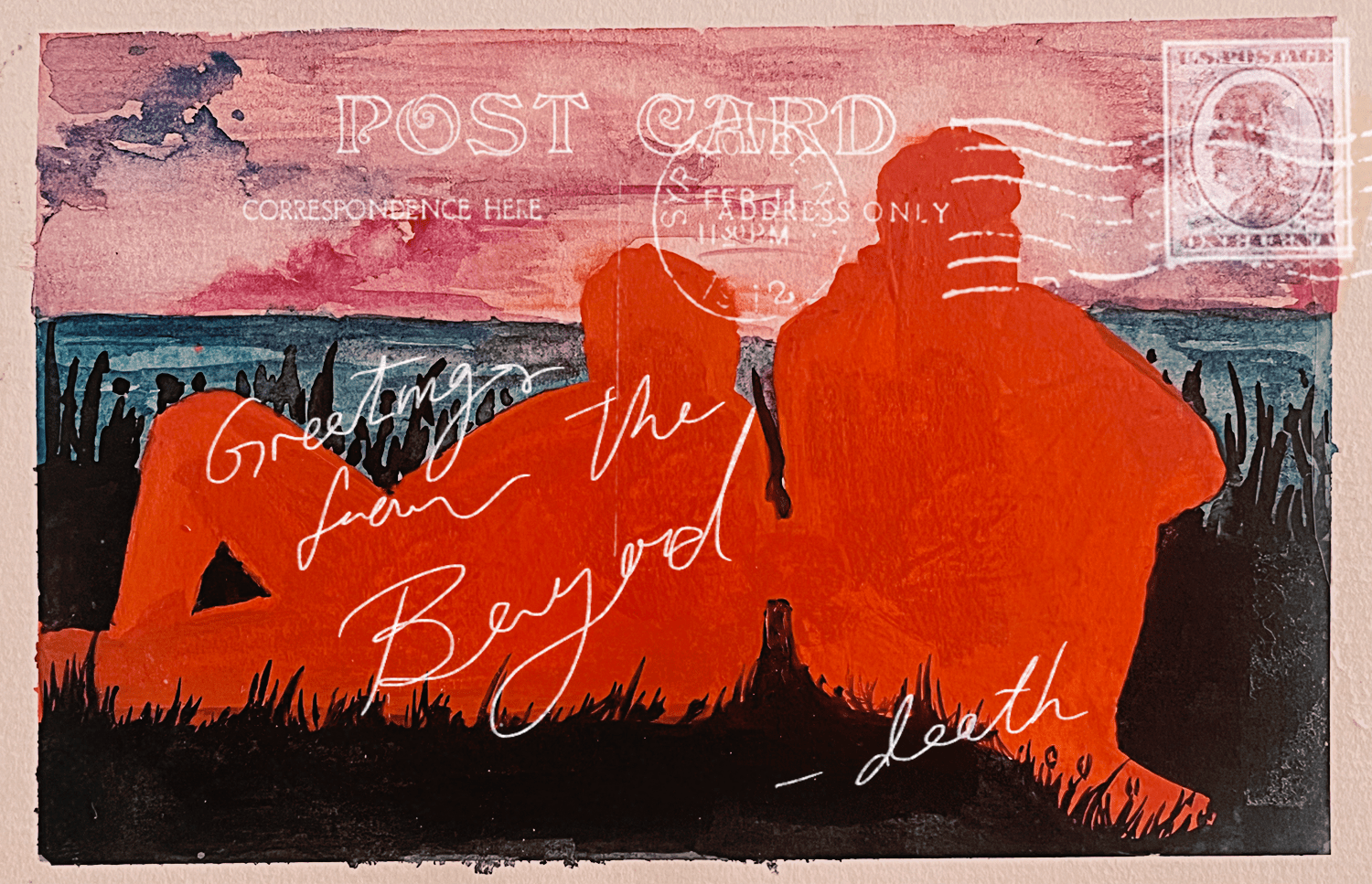

An ocean-loving comrade, Kiki Amberer, paints black angels in her 2019 poem Black Angels Do Exist:

here I stand, that violent tragic ghost

they warned you of.

didn’t you know that a black person living is invisible?

I breathe my own corporeality out hard

through my nose, it is cold

Sound — from its inception as a raw vocalisation through to a meticulously produced medium — is a political tool. From my years of working with sound in media production and activism, I’ve come to define sound as a tool of the defiant devils: a way of rethinking our relationship and treatment of the oppressed.

These politics are embedded within the conventions and practices of sound mixing. Like most people, I acquired my media knowledge from Western education, with its perspective constricted to the realms of this University and the white, heterosexual media outlets that overwhelm the colonial state of Australia. Even the most “progressive” channels follow the same conventions.

Conventional media coverage thus creates a binary monotonous environment where a perfect English-speaking journalist dominates over the news subject, usually in the third world with people talking about their struggles on their lands. The subjects then take up a smaller, pervasively edited space in these news commentaries rather than being the primary storytellers. who usually take a smaller, pervasively edited space in this commentary. Dr Rose Nakad, a Cultural Activist and USyd Media Academic, called this a play of the soundscapes.

According to Nakad, the dominant media uses the concept of Foreground and Background, which “can never express the complexity of things”. This complexity is made more obvious when we consider how the manufactured constructions of sounds influence how we imagine voices, particularly for those from communities and voices that transgress the conventional, so-called civilised Western framework which frames a lot of our audio production practice.

For instance, people in refugee camps are always recorded in an utterly silent, desolate space away from where they live and the background is usually a pre-recorded, overused sound of missiles shooting in the distance. By separating the bodies of the sound from their environment, tools of audio production perpetuate the image of this ghettoised, uncivilised native person who requires help from the West. When I discussed this with Nakad, she travelled back to her time working in the Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon. She recalled wondering, “How do I pick up a recording there that’s about that place, the rumble of that place, the earth of that place?”

Sound bites in their rawest form have the capacity to evoke immense political thinking. Where am I right now? Now that I have this sound, how do I preserve it? How do I mix it? How do I honour the experiences it contains? And even then, I find myself falling into becoming a slave to this corporate sound system too. Looking up “Middle East” when looking for music clips on royalty-free apps, mixing in a way that gives neoliberal ideas about a topic too much space, or lowering the volumes of protestors. The whole audio production industry gets to you, more easily than you’d imagine.

Soundtracks are visceral forms of data; often visualised through the ambiguous concept of frequency. Poet, essayist, and academic Anne Carson discusses how women of classical literature are “a species given to the disorderly and uncontrolled flow of sound — to shrieking, wailing, sobbing, shrill lament, loud laughter, screams of pain or of pleasure and of raw emotions in general”. The female and queer voice is always considered a deviation from the baseline of normality and practicality. Death and mourning cultures of the Moirologists of Greece, Opparis of South Asia or Yezidis of Armenia use high-pitched lamentations to mourn the death of individuals in privileged communities. Greek legislation criminalised professional mourning because the intensity of the lamentations polluted the sanctity of a male-dominated and logical society.

This idea of particular sounds as pollution still permeates contemporary practices of audio production. Nakad, in her teaching practice, challenges her students to work independently with commercial editing software. Using warrior poet Audre Lorde’s idea of dismantling the “master’s tool”, she challenges her students to think about the “political and historical consciousness of things”. In this type of practice, you use the voice of a high-pitched woman or a gender-nonconforming voice and make it the voice of resistance in your story. She also gives the example of using sound as a mechanism to mock the privileged, for example making an NGO leader’s voice fade out and be overtaken by working-class women resisting in the background. Through this choice, they become the narrators of their resistance.

A phrase I find myself saying a lot is, “I love loud women.” Not the upper-class caste women who fill corporate rooms, but women and queer people who sing, cry and mourn with every inch of their bodies. Pakistani singer Iqbal Bano quivered every time she sang a line against the militarist rule. Egyptian legend Umm Kulthum sang in a bodily fashion that transgressed any conventional vocal range. These are the voices that I love.

First-world notions of voice and power demonise women to such an extent that when DjabWurrung Gunnai Gunditjmara senator Lidia Thorpe shows militaristic defiance towards this white settler colonial project, she is called hysterical by people like our Prime Minister — who somehow claims to be a voice of the working class but only when it serves him. It’s this idea of baseness and rationality that dominates political commentary, even as it has been a historically imperialist mission to bring the defying native people back to this sociopolitical consciousness.

So, when we hear sounds, when we make sounds, and when we are endowed with editing software and equipment, it is integral to look at the impacts of the decisions we make on the end product. Think about who you can hear, and who you can’t. Ask yourself, why might you be hearing the version that you are? Who is it supporting? Who is it not?

I feel the calmest when I’m looking at varying movements of audio scales, falling into a focus adjusting atmospheric sounds from different regions and times, and working individually with each soundbite to make it a story of its own. The most radical productions happen outside of elite recording rooms. They happen in the crevices of our lives. On the streets, in WhatsApp recordings from someone’s room, in Indian forests or in the everyday actions of their work.