USyd students are very good at pretending to be lawyers. In April, Robert Clarke, Shruti Janakiraman, Jake Jerogin, Hae Soo Park and Sarah Purvis were crowned world champions of the Jessup International Law Moot Court Competition, beating out over 500 teams. (Jessup bills itself as “the world’s largest and oldest international moot”; think of it as like the Olympics for law students.)

But it didn’t come easily. The Jessup team spent six days a week for six months, researching niche areas of international law, writing submissions and preparing oral arguments. “It was brutal,” says Clarke. “I knew, intellectually, what [the commitment] was going to be … but I didn’t expect to feel so drained.” For Park, who did a clerkship while doing Jessup, “I was working 10-day weeks … I had to manage my time efficiently.”

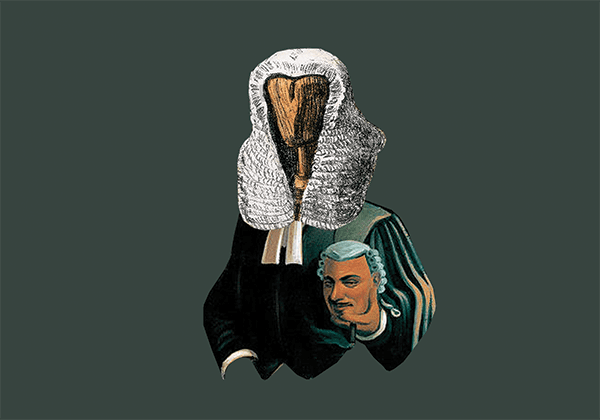

The world of competitive mooting – where students argue cases in a simulated courtroom – has a reputation for being formal and ostentatious, made for students who enjoy dressing up in suits and talking in legal jargon. In a sense, learning how to moot is not just about making watertight arguments, but also about playing the role of barrister.

At USyd, it’s a rite of passage for every first-year law student to try a moot and be promptly eviscerated by a judge. “Facing a scary bench for the first time is terrifying,” laughs Janakiraman. “Judges will try to throw you off course.”

Given this likelihood of humiliation, and the preparation that goes into high-level moots, why do students dedicate their time to this singular pursuit?

Purvis says that as far as a practical learning experience goes, “this is as good as it gets.” In a law school infamous for its harsh marking and its penchant for old-school, 100% closed-book exams, mooting challenges students to apply their knowledge in a near-real-world scenario.

It also dispels assumptions about the profession. For example, winning a case, while it involves rational argument, also rests on making a personal connection with the judge and understanding how to persuade them. “The stereotype of a mooter is assertive, coldly rational, able to remove themselves from a situation,” explains Jerogin. “But it’s really an EQ thing [to] maintain control against a judge and know what they want to hear.”

The team recalled a low point when they placed in the bottom half of teams at the national finals, unexpected for USyd. “It really was a wake-up call, to build the resilience to come back stronger,” says Clarke. He says mooting requires you to question your own assumptions and think quickly and logically. “When a judge hammers you with questions and you’re contorted … you have to work it out as it’s happening.”

Part of mooting’s popularity is because USyd is a renowned training ground for aspiring mooters. It holds the record for the most Jessup titles (six), and the Sydney University Law Society’s (SULS) student-run mooting program is by far its most well-resourced and highly-attended portfolio. For Purvis, who was SULS’ Competitions Director in 2020, watching a USyd moot in Year 12 was why she wanted to study at USyd.

Since SULS revamped its mooting program a decade ago, a supportive community has formed to mentor younger students. Purvis points to Alyssa Glass, best oralist in 2017’s winning Jessup team and a legend in USyd law circles, who established the Women’s Mooting Program, which has led to more women participating in and winning moots. (Glass was often the first, after their coach John-Patrick Asimakis, to call the 2021 team after moots, offering encouragement and advice.)

There are valid criticisms of mooting, however. As it tries to replicate conditions at the Bar, where barristers are predominantly old, white and male, some argue that assimilating into those conventions may not help students critically reflect on their role in the profession, or advance justice for minority groups historically dismissed by the legal system. “There’s a certain way of conveying that you’re knowledgeable and authoritative in a moot,” says Janakiraman.

While the majority of this year’s Jessup team are women of colour, which is no mean feat, the team agrees that privilege in mooting can operate through structural barriers “in a self-exclusionary way.” USyd’s success also comes from its institutional backing; not many other universities can say they recruited 30 volunteer judges, academics and barristers to judge Jessup practice moots.

It’s also no secret that performing well in a moot looks good on a resume. Experiencing the prestige that comes with being a seasoned mooter, however, requires an immense time commitment. For students who work long hours or who live far from university, it’s just not a viable option, which further reinforces structural barriers.

SULS has introduced mooting programs for women, queer students and international students, who remain severely underrepresented in the law. And for those who delve into this rarefied world, they seem to come out of it more confident. “It’s easily the biggest thing I’ve done at uni,” says Janakiraman, who has already signed up to another moot with her Jessup teammates. “I still find it really enjoyable.”