Joan Didion, journalist and author celebrated for her writing on American politics and culture, passed away two days before Christmas last year. Didion had a close relationship with death and grieving which she explored through writing. It was inevitable; the latter part of her life was so marked by death, with both her husband and her only child dying in the span of 20 months.

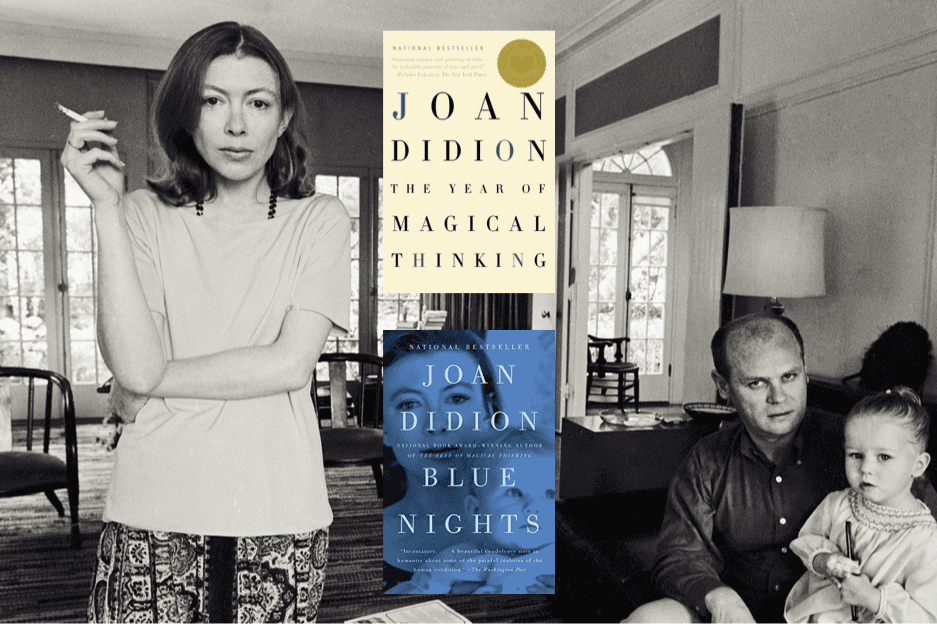

The command Didion exercised over her cold, clear and precise prose is famed. Well-attuned to the disorder of her society, Didion retained control in narrating the chaos ensuing before her, seemingly detached from the America she observed. But in recounting her experience with death and grief, perhaps only with death and grief, Didion allowed herself to lose control. Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking (2005) and Blue Nights (2011) reflect with unyielding honesty an unattainable desire for control in face of death.

A fifth-generation Californian, Didion’s early writing examined the tumultuous cultural and political climate of her coastal state. In 1968, Didion published a collection of essays entitled Slouching Towards Bethlehem, considered by some to have best captured the instability and uncertainty of 1960s California. Author Joyce Carol Oates once described Didion as “an articulate witness to the most stubborn and intractable truths of our time, a memorable voice, partly eulogistic, partly despairing; always in control.”

The title, Slouching Towards Bethlehem, was a reference to the W. B Yeats’ poem ‘The Second Coming’, a reference which likened the disorder of 1960s California to that of Yeats’ post-WWI Europe. When writing about California, Didion’s voice was always cool, detached, and almost apathetic. She was unaffected by the romanticisation and glorification of Sixties countercultures. Infamously, in Slouching Towards Bethlehem Didion recounted her introduction to a five-year-old girl, Susan, whose mother had given her LSD. She had been doing acid and peyote for over a year already. “Susan describes it as getting stoned,” Didion remarked with a frankness only she could execute.

Didion spent much of her later career writing about death. In 2003, Didion’s husband John Dunne died suddenly from a heart attack. That same night, their only child Quintana Roo lay comatose in Beth Israel North Medical Centre, New York. Quintana died not two years after her father.

The Year of Magical Thinking was published after Dunne’s death but before Quintana’s. In it, Didion expressed a clear idea of how she wanted to deal with grief. But she also recognised the difficulty of repressing the memories to which grief attaches itself. She called this difficulty “the vortex effect”. “This had seemed like a good line of thinking,” Didion said, recalling a time when she ruminated on Beth Israel’s rose-patterned wallpaper in an attempt to distract herself from grief. She ruminated on the building’s past. However, this ultimately brought her to her own, producing a whirling, uncontrollable mass of grief-tainted memories—”the vortex.”

The Year of Magical Thinking details the year after Dunne’s death. It chronicles Didion’s desperate and futile attempts to claim control of the tragedy that afflicted her home. Dunne died at the dinner table on the day before New Year’s Eve. In the following months, Didion searched for a logic or order which might make sense of the chaos that had ensued: “I have spent a great deal of time trying first to keep track of, and, when that failed, to reconstruct, the exact sequence of events that preceded and followed what happened that night”. Tracking memories and seeking explanations, she said “information was control”. In late January of the next year, Didion acquired the log of her apartment’s doorman for December 30, noting the paramedics’ arrival and departure time. Could it have revealed to her the exact moment Dunne died? Or if there was a chance of survival, had the paramedics arrived sooner? Didion articulates how information is control over death and grief, even after the fact.

In Blue Nights, Didion reflected on the horror of realising that it is impossible to foster that impenetrable safety parents might desire. Quintana had worn white flowers braided into her blonde hair on the day of her wedding, just six months prior to her death. At that time, she had been sick for almost two years; a case of pneumonia unexpectedly progressed to septic shock and an induced coma. After Quintana’s wedding, Didion suggested a holiday to Malibu, California. For Didion, it was a way to return to Quintana her childhood innocence and safety; “I wanted to see Malibu colour on her face and hair again”. Upon landing, Quintana collapsed onto the asphalt. Her recovery was not yet sufficient to endure the pressure from the plane. It was this injury, together with multiple illnesses, that led to her death three months later. Blue Nights did not celebrate or commemorate Quintana’s life as one might expect from a memoir. “You have your wonderful memories,” people would remind Didion. But she did not “want reminders of what was, what got broken, what got lost, what got wasted,” revealing that perhaps she never could have provided the impenetrable protection for Quintana that she imagined.

What does the late Didion’s work reveal about death? Perhaps nothing. “Grief turns out to be a place none of us know until we reach it,” Didion said. But she gestures towards some revelation on grief and death in the last paragraph of The Year of Magical Thinking. Didion reminisces on cave swimming at Portuguese Bend, and her anxiety about missing the swell. “The tide had to be just right. We had to be in the water at the very moment the tide was right,” wrote Didion. “Each time we did it I was afraid of missing the swell, hanging back, timing it wrong. John never was. You had to feel the swell change. You had to go with the change. He told me that.”