“Loss comes in many forms. Sometimes it creeps in quietly, unobtrusive until it is felt. Other times it comes in like a wrecking ball.” – Sam Langford

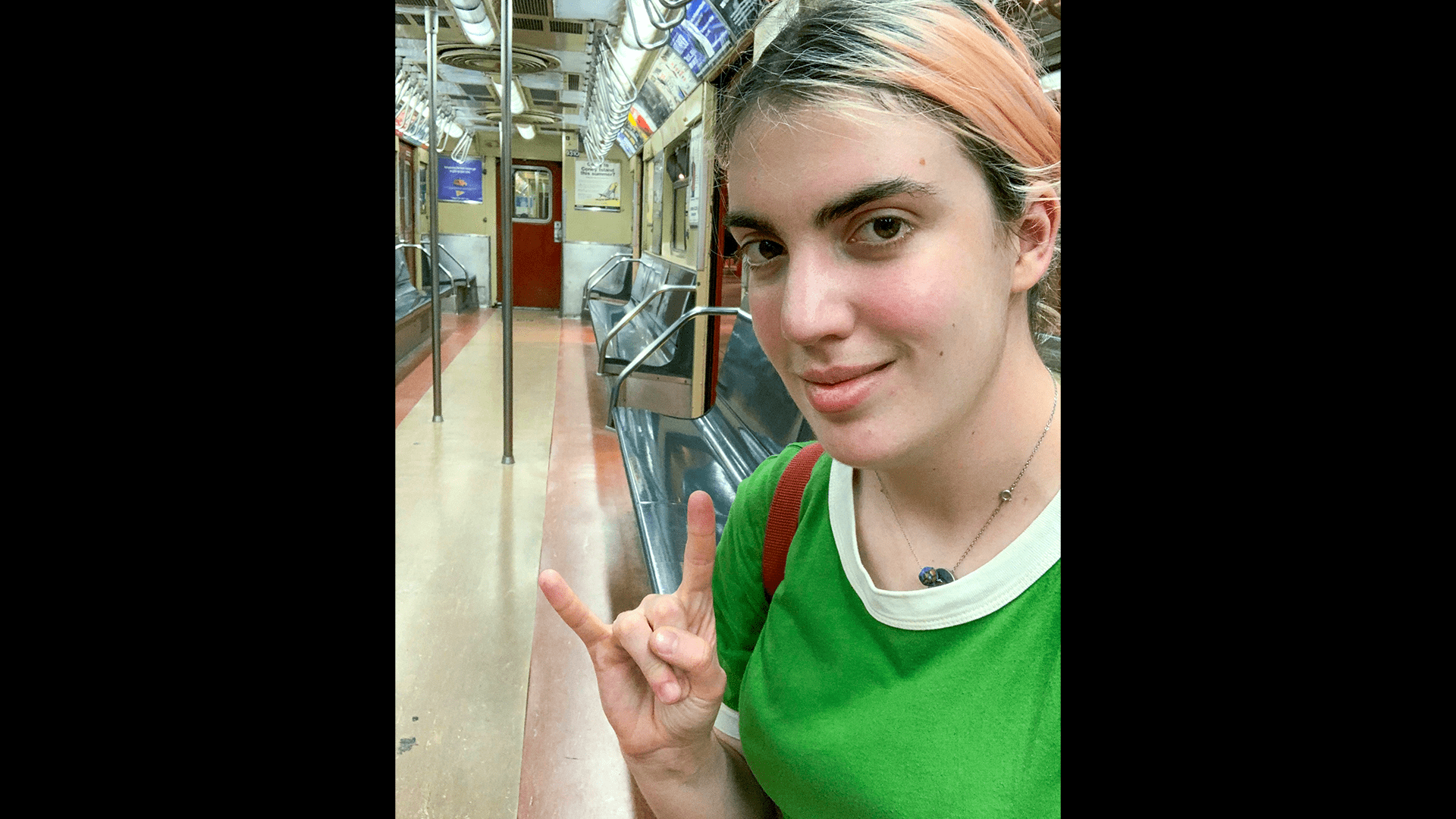

On Saturday May 16, we lost Sam Langford. They were 23 years young and truly embodied the spirit of creativity and activism intrinsic to Honi Soit, which they edited in 2016.

To say Sam – or “Slang” – was smart seems an understatement. They arrived at university on a Hillsbus as a 17-year-old wunderkind who skipped kindergarten, duxed year 12, and found themselves in the debating society explaining to people three years their senior and three times their ego the flaws of libertarianism when they weren’t even old enough to be in the pub.

Transferring from psychology to political economy, Sam earnt HDs and The Paul M. Sweezy Prize despite a packed schedule of involvements: they edited BULL magazine before this paper, alongside roles in SHADES and the Enviro Collective. Editing Honi Soit lets you do what you want, and that’s how we learnt Sam could do anything: write, draw, code – Sam could pick things up in days that would take others months. They co-designed the Honi Soit website which is still used today, learning web development along the way.

You can’t defame the dead, so it should be said the obvious corollary of this intelligence is Sam, who used she or they pronouns, was a big nerd who wrote fan fiction and kept bees. When they passed, Sam was taking one of their brother’s programming courses, just for the fun of it.

Two of their greatest joys were puns and fonts. The most perfect convergence of these two things came one late night in the Honi office when, watching one of their fellow editors completely butcher the design of a headline, they burst out: “Kern you not?” Their favourite font was Futura, a sans serif designed in 1927.

This nerdiness was threaded through their relationship with this newspaper, first as a reporter – their debut was an op-ed about cutting their hair short, their last story an exclusive historical investigation into the burial of thousands of USyd textbooks under a western Sydney cricket pitch – and then an editor. Sam kept an archive of every copy of Honi Soit they read. Not just the ones with their byline, or the ones they edited, but a perfect anthology of every copy they came to possess.

As an editor, they were as fastidious as they were kind: the minutes from our 7am Tuesday meetings – which Sam would attend after often having emerged from Sunday night’s lay-up as a Monday afternoon tutorial was getting underway – show countless times they pushed to work with a reporter on an idea, rather than just can it. They wanted as many people as possible to be able to experience the joy they did from being involved with the paper.

Sam was also a big jock, as they would remind you only half in jest. They were into deadlifting, played soccer and loved bushwalking. They once nearly got into a fight with some people at The National who were moshing in their personal space. In true Sam style, they were friends with their adversaries by the end of the night.

Fitness became an increasingly important part of Sam’s life after being diagnosed with epilepsy in 2018. Together with their dad – a physio and ex-NRL player – they developed a training regime to give their body the best chance against their condition. In his eulogy last Friday, he proudly announced the stats: they were deadlifting 100kg this month and, unable to do a chin up before starting the regime, they were now knocking out five.

In their work in student media and later in roles at Junkee and SBS, Sam showed a commitment to telling the stories others wouldn’t, or didn’t know existed. Many of the voices in the outpouring of grief after their passing were people who they gave a voice: the queer community, survivors, the ones being screwed over. Sam was dedicated in covering and caring about the closure of public housing at the Sirius building at Millers Point and brought activism to their own workplace when they unionised the Junkee staff (before promptly making a Tony Abbott meme about it).

The transition to adulthood can see many people’s relationships with their family strain or become distant, but Sam loved theirs and their company more than anything. A visit to Sam’s family home could mean your entry into a Langford pool volleyball tournament or competitive completion of the Good Weekend Quiz. Their mum, Catherine, dad, Andrew, and younger brothers, Jack and Patrick, were not just their relatives but among their best friends.

And what a fortunate group to be part of. Sam had an incredibly low tolerance for bullshit about serious things, and an abiding love of bullshit at all other times. They had so much time for their friends and, despite their own numerous successes, were always so proud of them. New jobs, hobbies, relationships and disappointments: Sam kept track of it all. Except, of course, for what any of these characters in their friends’ stories looked like; extremely face blind, Sam was once approached by a close friend’s friend to congratulate them on a piece in Honi and, with the most compassionate and kind tone, replied, “I am so sorry. Who are you?”

It sucks to know we will never again hear Sam say “hey buddy” followed by “gimme one sec” as they stopped to take a picture of an ibis, or a particularly aesthetic pile of litter.

The quote at the start of this obituary is what Sam had to say in a 2016 ode to the now-demolished Transient Building, an asbestos-ridden Manning Road structure where cockroaches sat in on linguistics classes which Sam, in line with their Instagram-documented love of the Brutalist and the butt ugly, had a soft spot for. In the piece, they later asked: “How to mourn something so patently shit?”

We don’t know. We just wish they’d told us how to mourn someone so patently wonderful.