As one of ten thousand who have chosen to seek refuge from human lands here during the sweltering summer, the jostling crowd makes me feel caged. But as I foray further and further down the paths, I am immersed into a different world each time. In the morning I am underwater, sprayed by a cheeky seal and enrapt by the gaping pelican. By noon I have flown to Sumatra, and spend my time tiger-spotting as they hide under cool leaves. As the air cools I am in a rainforest, a menagerie of butterflies and birds dart above my head, painting a rainbow. The sun sets and I wave the tarantulas goodbye, pressing my finger against the glass as if I am touching his furry limb. As I leave, I fondly recall how I saw the animals of the world in one short day.

The modern behemoth of Taronga Zoo had humble beginnings as New South Wales’ first public zoo in 1884, situated in Moore Park. However, within twenty years, the zoo’s Secretary Albert Le Souef decided the space was too small, and no innovation could be born in austerity. The Zoological Trust sought a beautiful region of land overlooking Sydney’s dazzling Sydney Harbour shores, and brought Noah’s Ark to shame with the transfer process of animals to the Mosman oasis. On 7 October, 1916, the gates were opened and guests began flooding in like a gush of water through a ruptured dam.

In the span of a century, the zoo’s main activities transformed from hosting cruel chimpanzee tea parties to focussing on the breeding and release program of Australian native species. Influenced by the social mores that underpin our global understanding of animal welfare, the zoo serves as a mirror reflecting our beliefs. In the early days of its inception, Taronga Zoo provided carnival-like entertainment for its guests, often at the expense of the animals, who served only to be observed or exploited. In the days before television, families had ‘ants in their pants’ to witness exotic creatures who heralded from light-years away. As a result, many expectations befell the zoo. So, to please its guests, the zoo offered interactive experiences such as elephant rides; it was seen as an amusement park, rather than the champion of education it is today. Merry-go-rounds spun guests until they were dizzy, and the colourful miniature train garnered more interest than the animals themselves.

In its early 20th century exhibits, there appeared to be little to no thought given to animal wellbeing. We now enter zoos and become immersed in a simulated wilderness, yet contemporary zoos were constructed as a microcosm of weirdness, wonder, and whimsy. This spoke to a disillusioned Australian population in the inter-war years, the zoo’s outlandishness paving an avenue of escapism for widowed mothers and their children, or a place for family bonding after the return of veteran fathers. For the zoo itself, there was a fierce ‘rat race’ to offer attractions more exciting than its competitors. In 1932, the zoo opened an ‘animal kindergarten’ with two mischievous monkeys, Freda and Freddie, who were forced to wear suits and ride a bicycle, to the delight of onlookers. These ‘performers’ gained much traction, as guests were so enamoured by watching animals mirroring human activities that four years later Taronga constructed an expansive ‘monkey circus’ arena, with a seating capacity of a thousand.

Monkey-sized tandems and unicycles were built and donated by Australian bicycle manufacturers Speedwell as a form of product placement. One of their star performers, Mabel, debuted on the front page as a ‘Zoological Cycling Champion,’ as she could ride around the circuit up to twelve times each day. The Northwestern Courier published in 1938 iterates how she “humanly shows her appreciation” for the applause, demonstrating that the exploitation served to expose human-like qualities in the primates; even in the modern-day, we indulge in the demonstration of genetic similarity between monkeys and humans, and marvel when they imitate human behaviour, rather than treating them like an animal in their own right. Humans were incontrovertibly the zoo’s only focus, exemplified in a photo captured in 1960 of Alfred Hitchcock sitting on a tortoise’s shell. Hitchcock toured the zoo to promote the upcoming release of Psycho, and such a mission was placed higher than animal welfare; although a tortoiseshell may appear hardy, bearing weight can lead to injuries and respiratory problems. It is imaginable that this information was not known at the time, showing how ignorance underpinned animal malpractice.

Today, the seal and bird shows remain integral to Taronga Zoo, but they differ significantly from archaic circuses –– the show varies each day depending upon the ‘performers’ themselves. The seal show serves as an educational platform for conservation –– the spectacle’s key sponsor is the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC), a not-for-profit organisation that sets sustainable fishing standards. The presenter of the show encourages the audience to purchase fish bearing the MSC tick. A memorable moment of the show, when the seal itself pulls a string to reveal the MSC banner, elicits ‘awws’ from the audience; the seals thus contribute directly to the zoo’s campaign of sustainability.

The pertinent difference between the shows of today compared with those of the past is the consideration of animal welfare as paramount. I remember sitting in the crowded seal show audience, breath bated, awaiting the famed twists, jumps, and somersaults. On that day, one of the seals decided he was not interested in performing, and chose to mischievously glide alongside the tank instead. The presenter chuckled and explained that it was mating season, so Marley was a tad distracted by his female companions in the adjacent tank. Rather than feeling disappointed, we were reassured that the animals were not forced to perform against their will. This empathetic approach strikes the balance between creating an enjoyable and educational experience for guests, whilst ensuring it is not at the expense of the animals’ wellbeing.

Drawing from a newfound scientific understanding of animal welfare, and a community desire to protect their wellbeing, Taronga Zoo became a trailblazer in its approach to animal care. Upon reviewing its deplorable practices in 1967, staff realised modifications were essential. The winds of change were upon them, and the zoo and its guests became more attuned to the needs of animals. Undressing its image of an entertainment venue, Taronga exchanged its rides for open-air exhibits, such as the walkthrough rainforest exhibit and waterfowl ponds. It constructed a Veterinary Quarantine Centre to care for sick or injured animals, and an Education Centre to engage guests in conservation conversations, rather than providing a lofty ride on an elephant’s beaten back. In 1977, Taronga opened the Western Plains Zoo, located in Dubbo, which was praised for its large, open-air enclosures that replicated the environment of the wild. As a not-for-profit organisation, all of the zoo’s revenue is dedicated to its modern-day in-situ and ex-situ conservation efforts.

In the 1970s, the zoo also became subject to increased regulations and governmental legislation due to an increased societal impetus to limit animal cruelty. The NSW government passed the Zoological Parks Board Act [1973] which stipulated that a Board oversees the management of the zoo, in charge of “carrying out research and breeding programs for endangered species” and “conducting public awareness and education programs about species conservation and management.” The discourse surrounding park management is a far cry from earlier legislation passed in NSW in 1956, which did not contain the words “species,” “conservation,” or even “animals.”

In addition to being an era of cultural transformation, counterculture, and revolution, the 1970s also saw the emergence of philosophical debate surrounding the sentience and suffering of animals. Australian philosopher Peter Singer published the inflammatory work ‘Animal Liberation’ in 1975, which sent shock waves through society; Singer questioned the cruelty to which we subject animals for our own entertainment, drawing controversial comparisons with human exploitation and mass murder. He was one of the first philosophers to tie utilitarian theory to animals, and thus brought animal welfare to the forefront. Doubt was immediately cast over zoos, and Taronga and others in Australia rehabilitated their image to focus on promoting, rather than hindering, animal rights.

Today, the modern notions of conservation are so core to Taronga’s mission that it is difficult to believe this was not always the case. Taronga Zoo operates under strict scientific direction that informs its programs. Taronga scientists are currently undertaking research in a broad range of fields, such as ecology, biodiversity and animal behaviour, to formulate the best method to protect an endangered animal. From the Big City Birds project which analyses avian adaptation to urban environmental pressures, to the Shark Attack file reviewing potential deterrence strategies, to tracking down the breeding origins of green turtles via stable isotope analysis, researchers clearly leave no species behind nor habitat unturned. Importantly, scientists also focus on researching the prospects of releasing animals into the wild, studying the viability of their habitats and the prevalence of predators.

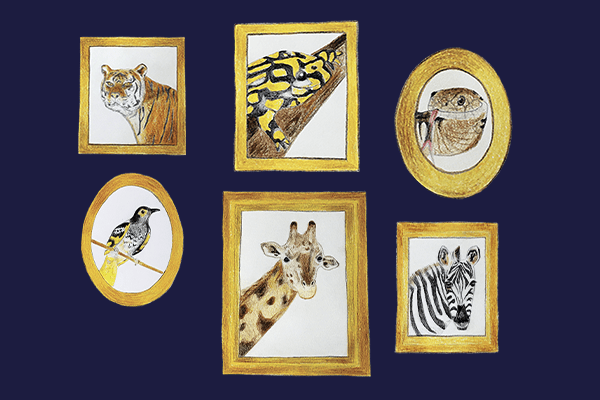

Habitat research and breeding programs converge in one of Taronga’s current conservation projects. It is focused on the regent honey-eater, a critically endangered native Australian bird, that suffered population decimation in the early 2000s. Since 1995, Taronga’s mission regarding the conservation of this species is “breed to release,” however, awareness and prevention of the environmental factors that endanger these animals is key to successful release in the wild. According to conservation biologists Tripovich et al., “whilst every effort is being taken to optimise the breeding program, the main threatening processes i.e. deforestation … need to be addressed if the species has the potential to become self-sustaining.” The rapid breeding of regent honey-eaters is crucial not only for the survival of the species, but that of the ecosystem, as the birds are vital pollinators of native Australian flora.

So far, Taronga Zoo has bred and released 295 of these yellow-and-black-feathered birds, alongside attempts at habitat restoration; staff and volunteers have planted over 3000 trees at Capertee Valley in NSW. Following their release, scientists monitor the animals’ husbandry practices and also how the once-captive birds adapt to the wild environment. Researchers discovered that exposing fledglings in Taronga’s aviary to wild regent honey-eater song improved their chance of post-release survival by 12%, and certain breeding conditions, such as parents only producing one clutch of eggs a year, also improved survival prospects. Research illuminating strategies to maximise post-release success is ultimately key, as without this, breeding programs are futile in changing a species’ endangerment status.

The corroboree frog, a hopping artistic masterpiece, has also been placed under the conservation spotlight. This visually iconic yellow and black frog is endemic to the Southern Tablelands region of Australia. But the species is unfortunately critically endangered, threatened by fungus and climate change destroying its alpine habitat. Taronga scientists have worked on applying Assisted Reproduction Techniques to amphibians, inducing sperm-release and implementing protocols surrounding sperm storage, which could open the door to gene transfer between species, boosting conservation prospects. Collaboration between Taronga and the University of Wollongong has also facilitated research investigating nutritional modification –– giving the frogs a ‘silver spoon’ start to life. A team of evolutionary biologists are testing the effect of dietary carotenoids, the orange compound colouring pumpkins and carrots, on corroboree frog fitness. Previous literature in the journal Animal Behaviour suggests that carotenoids can improve the escape performance and hopping distance of a fugitive frog fleeing from a predator. Scientific research is thus indispensable to the effective preservation of species, as it ensures threats are mitigated so frogs are not released into a ‘lion’s den’ promising certain death.

The corroboree frog and regent honey-eater form two of Taronga’s ‘Legacy species’ –– in 2016, the Taronga Conservation Society announced a ten-year commitment to the conservation of species, five of which are Australian autochthones. This demonstrates their approach to strike a balance between the preservation of both native species essential to Australian ecosystems, and foreign critically endangered species due to the zoo’s capacity to accommodate these animals. The zoo’s breeding programs of animals harking from all four corners of the globe has proved remarkably successful, as it is the birthplace of animals from Sumatran tigers to Asian elephants.

Importantly, our understanding of conservation has been reshaped to encompass both in-situ and ex-situ efforts. Although in dire cases of endangerment, animals need to be removed from the threat and placed in captivity for restoration and recovery, a large portion of conservation efforts should be directed to in-situ habitat rehabilitation, which does not involve disruptive relocation. Taronga has a grants program that allows communities to harness their knowledge and lean on aid to promote conservation efforts; farmers in Africa have utilised the money to install beehives around their crops, to prevent human-elephant conflict when the curious creatures raid the harvest. Empowered communities in West Kalimantan, Indonesia, used the money to form a Wildlife Trade Monitoring Unit, to curb illegal trade and logging. Fieldwork is also indispensable to gauging the population and security of vulnerable species in the wild, as communities use methods such as camera trapping and ID-based identification.

Arguably as essential as scientific research and breeding programs is the communication of the importance of conservation to a wider audience. I spoke to Kerry Staker, who holds the role of Community Educator at Taronga Zoo. She comments on the importance of sharing the principles of preservation and sustainability in an “uplifting and inspiring” manner. “Government communication strategies are often misdirected,” she claims, as they “rely on scare tactics and fear-mongering.” Government rhetoric surrounding conservation is also limited: in 2020, conservation groups such as WWF and Birdlife Australia criticised the Morrison Government for rolling out biodiversity legislation identical to Tony Abbott’s failed Act. Current conservation laws offload power and burden to state governments, without codifying measures to protect endangered species and fragile ecosystems, or setting national environmental standards.

What is even more indicting is Morrison’s 2019 claim in response to a United Nations report, urging Australia to pass biodiversity laws. He asserted that legislation was “passed last week” –– this was debunked as incorrect. Furthermore, environmental working groups are urging the government to recognise the looming threat of climate change and its destructive effect on biodiversity. A statutory review of the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act [1999], released earlier this year, states the Act lacks clarity and outcomes. The scathing review suggests numerous important reforms, including the directive to “respect and harness the knowledge of Indigenous Australians to better inform how the environment is managed.” Furthermore, the review communicates the dire need for Indigenous involvement in environmental decision-making and legislation that protects Indigenous cultural heritage.

In the absence of the government taking responsibility, Kerry Staker affirms the importance of equipping the next generation with an understanding of sustainability. “6-year-olds can draw, and write stories,” she claims; this is instrumental because they then share their passion to save animals with their parents, family, and peers. Taronga ensures to target their conservation campaigns to children to fan the flames of their profound love for animals, allowing the fire of their passion to proliferate and spread through their community. Taronga hosts an annual ‘Boral Eco-Fair’ where sponsors come together to form a market, with stalls teaching children different elements of sustainability. Childrens’ faces are adorned with painted native animals, and some burrow like bilbies into a book about the Dreamtime and the environment. In some ways, the zoo is still like a carnival to a child, but the conservation-themed games they play trigger thought, not adrenaline. As well as learning important lessons about fostering sustainable daily habits, children are also just encouraged to deeply love animals of all species; this is conceivably the most important factor in sparking change.

A recent development in Taronga’s approach to conservation is its respect for, and reliance on, Indigenous knowledge. Taronga is an Aboriginal word translating to “beautiful view,” named after the Indigenous name for the land which the zoo occupies today. The zoo, operating on unceded Cammeraigal land, recognises its Indigenous history and the importance of Indigenous involvement. Importantly, the zoo is committed to hiring Indigenous staff who can run campaigns that draw from Indigenous knowledge, such as a bird show centred on the Dreamtime during NAIDOC week. Brewinna elder, Colin Hardy OAM, partnering with Indigenous staff, notably leads the popular ‘Animals of the Dreaming Zoomobile,’ wherein children learn about Indigenous knowledge about nature through storytelling and song. Kerry Staker comments on how the vast body of Indigenous knowledge of sustainability informs their work every day. Although Indigenous people did not use the word ‘conservation’ per se, they “thought about the concept of generational existence,” and “not fishing all the fish,” to ensure the perennial existence of all species. However, Staker believes we could lean on their knowledge more, noting that their approach to sustainability is calm and reflective, contrasting the Western crisis response to ecological issues. “We need to work slowly,” she explains, “there’s a long way to go.”

For the fourth time since it first opened its doors a century ago, restrictions have forced Taronga Zoo to shut. The zoo still attempts to share its message of species preservation and sustainability through a televised livestream of the animals and free daily virtual keeper talks –– no matter the circumstances, the pressing need for conservation efforts cannot be swept to the side. As our animals and world evolve, our approach to conservation transforms alongside them.