George Gittoes and Hellen Rose have been to the most dangerous, hard-to-reach places on Earth. The pair meet and document the real people, real stories, and authentic traumas of communities caught in conflict. Whether the war is between nations or city blocks, George and Hellen have forged lasting relationships in their endeavour to connect with people in the midst of war and violence.

George and Hellen sat down with Honi over a number of video calls to give insight into the work that has taken them across the globe, chasing conflict instead of running from it.

Most recently working in Jalalabad, Afghanistan, George sent Honi live dispatches of his time meeting with Taliban leaders and working alongside the local community, as well as those written during his five months in Ukraine earlier this year with Hellen.

“We would create something out of destruction,” said Hellen, referring to her documentary and artistic work in Ukraine.

“With the arts, what you do is aim invisible golden arrows at the heart of evil.”

Documenting destruction and loss is a foundational element of the pair’s work, and is vital not only as art in its own right, but as a precious and wide-reaching historical record. Their art varies widely in form — George creates drawings and paintings, while Hellen is primarily a performance artist and musician. While travelling, the pair produce poignant films together, spanning both documentary and entertainment genres.

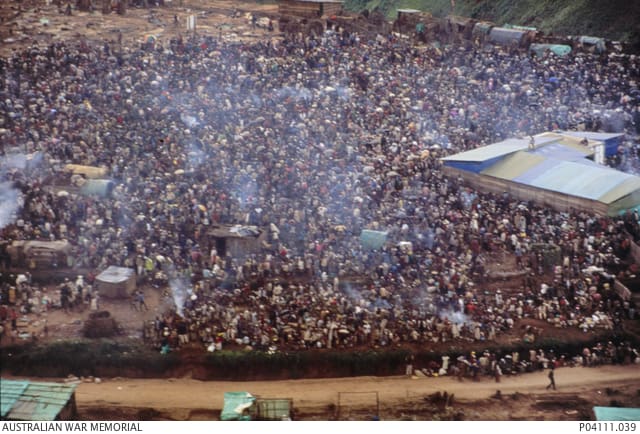

Speaking to his work documenting the Rwandan genocide, George writes that the Kibeho massacre was “the harshest experience of my life.”

The Kibeho Massacre took place on 22 April 1995, with the Rwandan Patriotic Army killing over 4000 men, women, and children at an overcrowded camp for displaced people following the genocide.

“As I hitched a ride back to Kigali in a military ambulance, I looked over to the two paramedics,” George writes.

He remembers thinking at the time:

“‘This has been a terrible thing to see but if we had not been here, those we have managed to save would be dead. Plus, I have the films and drawings in my bag which will mean the atrocities committed in this massacre will not be forgotten or hidden.’”

The United Nations went on to use his photographs as evidence in a war crimes investigation.

Australian Forces in the field. Kibeho, Rwanda.

The killing fields of Kibeho

Hellen and George do not travel with ‘fixers’ who typically forge a safe path for visiting journalists. Rather, they go solo, with cameras in hand, journeying through war zones with the support of locals. Their work straddles the line between art and documentary, with George noting that he is “trying to push the [documentary] medium” to create a new form.

Alongside producing their own art, George and Hellen facilitate the art practice of the communities they enter. From adapting bombed cultural centres in Ukraine to building institutions from the ground up in Afghanistan, the duo have taken collectivised, community-based art from 70s Sydney squat houses to the world.

But they are not without critics. The pair have faced pushback from mainstream media — including a producer who allegedly threw George’s breakfast in his face and decried him as “an insult to documentary filmmakers” — as well as local armed forces.

The Early Days

George and Hellen’s work establishing art collectives started locally in inner-city Sydney. They founded pivotal institutions such as the Yellow House Artist Collective in 1970, and The Gunnery in 1985. However, their roots lay even closer to home — right here at USyd, and even within this very rag, Honi Soit.

George attended Kogarah High School for a short time, before being expelled for “refusing to conform” he tells us, and moving on to Kingsgrove North. At age 19, and on a Commonwealth scholarship, George enrolled in an Arts/Law degree at USyd and attended a Power Institute lecture on campus by guest lecturer Clement Greenberg — a seminal figure of American art criticism who worked with artists including Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning.

Greenberg made an indelible impact on George’s career after seeing some of his paintings, remarking, “Shit man you are cool… this place is too far away, you’ve got to come to New York.”

Go to America he did. During his time there, George met and worked with Andy Warhol at The Factory, and spent time with Civil Rights Artist Joseph Delaney who introduced him to the Black Panthers.

In late 1969, George returned to Sydney and didn’t return to university — but he admits that “one year at Sydney University taught me intellectual disciplines…that have been incredibly valuable to me for the rest of my life.”

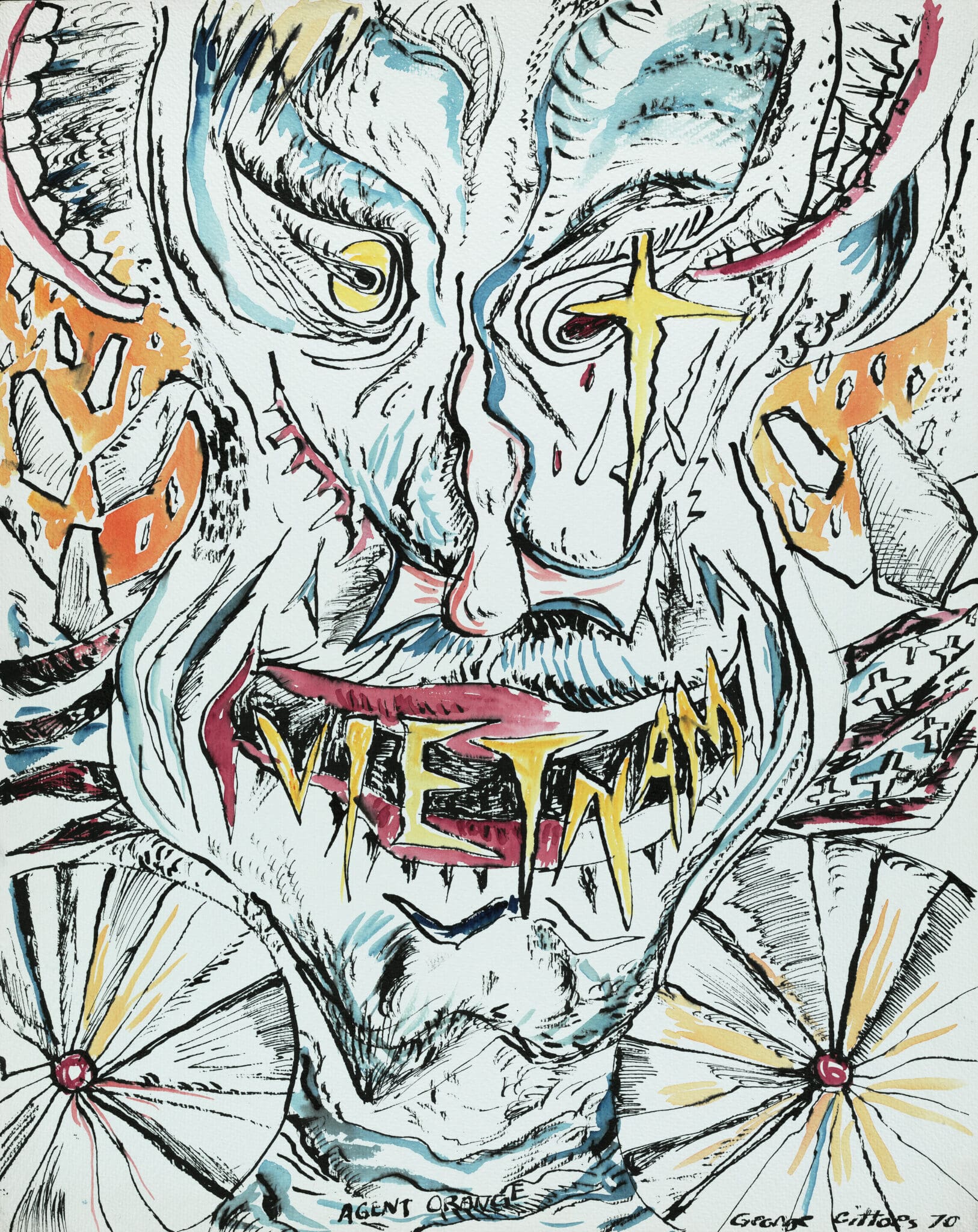

George continued to interact with USyd throughout the 70s by contributing art to Honi. “Everyone was on our backs to give them graphics in those days of protest against the establishment and the Vietnam War,” he said, even UNSW’s student newspaper Tharunka. A notable poster he made for Honi during this time was Agent Orange (1970), which depicts President Nixon as Agent Orange personified, in response to the raging Vietnam War.

The poster has since been bought at auction by the Australian War Memorial with the funds going to victims of Agent Orange.

In 1970, he founded The Yellow House (YH) alongside a group of artists including Martin Sharp and Brett Whiteley. Today, the house is considered fundamental to the zeitgeist of Sydney’s ‘70s art world, pushing the envelope of style and substance. It served as a haven for artists to live, work, and collaborate, and was the first of its kind in Sydney. The YH community staged multi-media events, exhibitions, and performances, and left their vibrant mark on the house itself (The ‘Puppet Room’, YH King’s Cross).

Similarly, George’s now-wife Hellen was a key organising member of The Gunnery squat in Woolloomooloo in the 1980s; to our delight, she used to advertise the famed artist-performance space in Honi.

“Honi Soit was always incredibly supportive of what we were doing down there, and of course some of us went to Sydney Uni,” she tells us.

The Gunnery was built at the turn of the 20th century; first, as a storage space for The Sydney Morning Herald, and then, when World War II began, as a defence and naval space by the Commonwealth Government. In the ‘70s, Sydney Punks transformed it into a countercultural haven.

“[We] had four band rehearsal studios, [and] we had the big cinema at the top,” explains Hellen.

“That was a venue. We had the shoebox theatre … It had a pit, so the audience was in the pit. We’d often have these wild cabarets with people who are all working in the ABC now.”

Despite the glamour of parties and thrill of rock-and-roll, Hellen emphasised the danger that residents of The Gunnery always co-existed with: “We were quite desperate to have somewhere to live… it was a homophobic world that we lived in. It was a rigid, unaccepting world.”

“The police absolutely hated us.”

Hellen tells us stories of waking up surrounded by police with German Shepherds, her friends being discriminated against and beaten in the streets, and criminals attempting to take over their space.

The Gunnery was only fortified by numbers — “we banded together … we were the most attended venue in Sydney at the time” — which meant they could “create [their] art, and also demonstrate against the horrors of the world that we were subjected to and many of our generation [were subjected to],” Hellen says.

“And that’s where I met George Gittoes.”

On the Frontlines:

Ukraine

More than forty years later, Hellen and George have since cemented themselves as a formidable artistic team. Working together from circa 2008, they have worked to establish Yellow Houses across the globe where they both create art themselves and facilitate the art-making of local residents. On the decision to continue making art in warzones for so many years, George was resolute.

“I saturated the media with my photos and stories about Rwanda but no one did anything to help fix the situation there,” George tells us. “So I changed my whole attitude and decided, and so did Hellen, that the only way to bring about positive social changes in these places, like Afghanistan, is to actually work there and do real things.

“It’s not enough to be a witness and an observer and bring that back to the lucky country of Australia.”

Most recently, George and Hellen have been working on the frontlines of the Russian Invasion of Ukraine. Packing bags full of cameras, canvas, paint, and musical instruments, they entered the country in order to document the war’s true impact on civilians and help in any way that they could.

The pair began their journey to Ukraine with a flight from Australia to Poland. The Australian Consular authorities had warned the artists that they would be crossing the border at their own risk, and against the wishes of the Consulate.

The Polish city of Przemysl lies just over 200km from the Ukrainian border. It was here that George and Hellen began their journey, hoping to catch a train across the border to Lviv before transferring trains to the Ukrainian capital, Kyiv.

At 3am on the Poland-Ukraine Border, George opened his laptop and wrote a dispatch. Hellen had already paid in advance for a hotel in Kyiv, and the couple planned to board a train there at 7pm the next night.

“The International media crews from the likes of BBC and CNN stay at big 5-star hotels with good facilities and hardened bomb shelters,” he writes.

“I value an atmosphere clear of speculation and hype. We will be with the locals – no one at the hotel we have booked speaks English.

“Hellen is writing in bed next to me, both hoping this will make us tired enough to go back to sleep. At any moment I could roll to my side and suggest to her we get a plane home, that what we hope to achieve is not worth the risk.”

George and Hellen did not go home. That following evening, George trawled the train platforms of Przemysl searching for an opportunity to cross the border. Eventually, a train arrived full of refugees who had just fled Ukraine.

“They were mainly women, children with family pets in carry cases, worried eyes peering out. Mateusz [a Polish mining executive] talked with them, and we realised there was a chance the train would be going back.”

George retrieved Hellen and their luggage from their car, rushing to passport processing. An English-speaking officer asked the pair, “but aren’t you afraid?”

Regardless of personal emotions, George later wrote that their motivation for persevering in the region was “to support the Ukrainian fight for creativity and freedom and independent thought.”

George wrote: “we made it in with the help and sympathy from [the English-speaking officer] and other female army officers who loved the idea we were Australian and artists. We had no tickets but that did not matter. We were ushered to a sleeping cabin in the last carriage and soon we were on the way.”

True to their word, George and Hellen arrived in Ukraine completely alone at the start of March of this year — no security, support team or bomb shelter, just a hotel booking and their luggage. But most importantly, they had their reputation as artists.

A Ukrainian local and pet photographer, Kate Parunova, reached out to George and Hellen on Facebook. Kate hoped that by sharing the true stories of Ukrainians in the warzone, she could help secure foreign support to defend her country. She had spent the early days of the war feeding dogs and cats across Kyiv, as many residents were forced to abandon their pets in the process of fleeing the country.

Kate met with George and Hellen in Irpin, a Ukrainian city just outside Kyiv. The three of them worked together to keep feeding animals in the region, with George and Hellen putting their artmaking on pause to assist Kate.

“Parallel with our film, the dogs became a priority,” George told us.

While working in Irpin, Kate was forced to delay her work in order to rescue her grandmother, whose neighbouring apartment had been bombed. Kate helped her to cross a bridge over the Irpin river to escape the city, and soon called George to tell him what had happened:

‘George, everyone’s been killed on the bridge, there’s been a terrible massacre,’ she said. Local residents would go on to refer to the incident as the ‘bridge of death’.

George, Hellen and Kate were some of the first people on the scene. George told us that this experience would have been “very hard for Kate, because she would’ve known the women and children and babies that were in the cars that had been killed.”

Some of the cars had words in English and Cyrillic written on the side, such as ‘stop’, ‘evacuation’ or ‘children’. The cars were bombed and shot regardless.

George wrote in a dispatch about the experience that “it has been a long time since I have experienced something as damaging as the Kibeho Massacre in Rwanda but the Bridge of Death at Irpin comes close.”

“Those who remained alive were executed in or near their cars,” George wrote in April this year. “The smell of death was overpowering.”

Many of the bullet-ridden cars also contained children’s toys and clothing. George describes one car that had an “expensive-looking book resting on the driver’s seat.” The book was a diary, dated until April 9th — “it ended the day the writer’s life ended.”

The bridge of death would not be George and Hellen’s only encounter with destruction and loss in Ukraine on such a grand scale.

On 17 March, the Central House of Culture in Irpin, standing between Russian forces and the capital city Kyiv, was the target of a devastating artillery attack. The house was built by locals in 1954 as part of the post-WWII reconstruction of the area, and was home to creative studios and classes, language clubs, concerts, performances, and public events.

Only two months later, on 20 May, another cultural centre, the Palace of Culture in Lozova, was bombed. President Zelensky said of the missile attack: “Absolute evil, absolute stupidity…The occupiers have identified culture, education and humanity as their enemies.”

Walking the streets of Irpin, George and Hellen were met with “house-by-house destruction”, and described the Central House as having been “made a target with every kind of ordinance in the Russian Arsenal”. The duo resolved to adapt the ruined structure as a workspace and curate an exhibition of 90 works by Ukrainian artists, dubbing their creation ‘The Yellow and Blue House’.

Not only did George and Hellen bring the House of Culture back to life in defiance of the Russians, both produced artworks on the site. George painted several oil works from within the rubble and destruction and Hellen staged and performed her work Armies of the Fallen.

In a dispatch, George wrote that while completing his painting, “returning residents of Irpin passed [by him] all saying how glad they were that art is happening again in this place of culture.”

Hellen also described one such encounter, in which some children arrived at the House of Culture after having “just come back to Kyiv and [seeing] their city just destroyed.”

Displayed on one of the walls was a caricature of Putin that George and Hellen had purchased from a market in Odessa. Hellen recalled one of the children punching the face of the artwork, as another asked why she was in Ukraine and what the exhibition’s point was.

“I said [to them], ‘Australian children think that Ukrainian children are the bravest children in the world… so George and I are here to stand with the people of Ukraine, and help the people of Ukraine tell the world the evil that’s going on.’”

Critically, Hellen expressed to us that the duo aren’t merely ‘war artists’, but rather “caretakers of culture and… caretakers of the soul”.

“Going into the destroyed house in Irpin was easy, it was ‘great we’re here again’, and finding everything that I could with my performance to turn that destruction into creativity,” Hellen said, reflecting on her years of turning dilapidated warehouses into living works of art, like The Gunnery.

Hellen attributes much of her personal and artistic philosophy to that of the Punk politics of The Gunnery: “This is what I always love about the Punk thing: it’s so brazen. It’s ‘cut through the bullshit’. It says ‘you are telling me I can’t do this, but hang on a minute, I’ve got my own brain. I’ve got my own thoughts. I’m going to do it.’”

The duo’s work in Irpin — bringing back visual culture and art to the site; a vein of cultural lifeblood decimated and abandoned by war — is entrenched in this mentality. “It’s about taking action…We can be leaders in any way that our imagination can conjure,” says Hellen.

George described the pair’s work in Ukraine as a part of their ongoing “war on war” that has taken them across the globe.

After four months and having overstayed their visa in Ukraine, Hellen and George felt conflicted knowing their ongoing obligation to the Yellow House in Jalalabad, Afghanistan could no longer be put aside. George and Hellen resolved to leave Ukraine. In late June, having captured as much of the war as they could through photography, film, and on canvas, the artists left on a train out of Kyiv.

Their journey out of the country was predictably fraught. They faced a series of train delays approaching the Polish border, as the electrical contacts connecting their train to overhead wires were damaged by a missile exploding above them while they slept.

Changing plans, technical concerns, and delays to evade anticipated Russian air strikes meant that the journey from Kyiv to Poland took over 24 hours. Their train completely broke down just kilometres from the Polish border, with George and Hellen being picked up by a contact in Poland who bravely crossed the border to collect them.

“We are leaving knowing that by doing the performances and show at the House of Art in Irpin we brought a sense of hope and victory amidst the death and destruction,” George wrote during his journey out of Ukraine.

“We used art and not guns to defy the Russians and it will be by maintaining the spirit of the Ukrainian people that the Russians will be defeated.”

They immediately began the editing process of their upcoming film Ukrainistan, which they shot during their time in Ukraine. George soon made his way back to Afghanistan via Pakistan to continue his work in the region.

“The whole time we have been in Ukraine we have been conflicted knowing we are needed, possibly more, in Afghanistan.”

Afghanistan

George first visited Afghanistan in the nineties to assist with a mine awareness program after the exit of the Russians and again in 2002, attached to Doctors Without Borders. He returned in 2010 with Hellen to begin filming the duo’s first Afghan film called Love City, Jalalabad. In the same year, they established The Yellow House Jalalabad (YHJ).

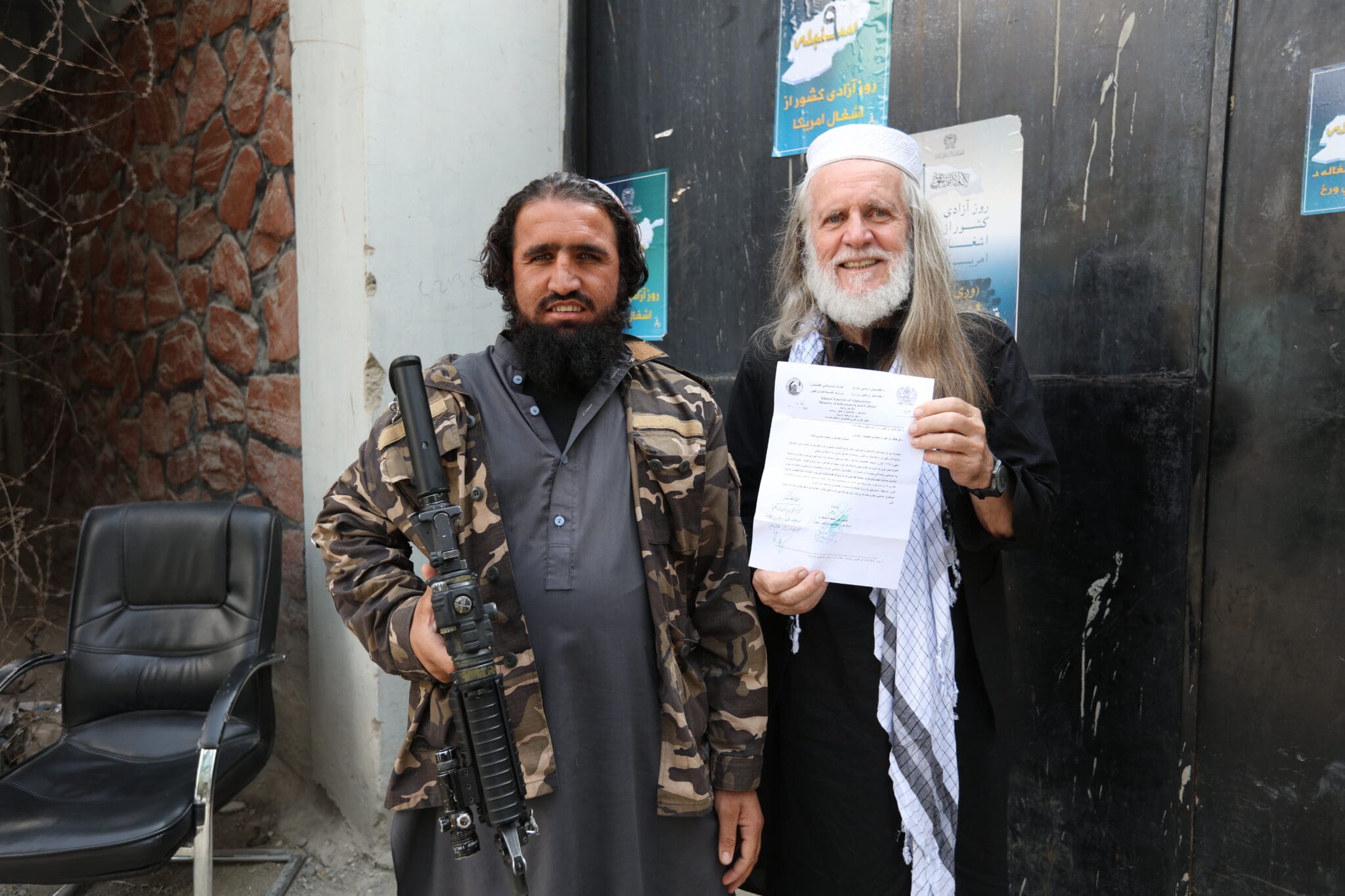

On returning to the area in September this year, following troubles with the Australian Government not providing key visa documentation, George writes in a dispatch:

“I had no idea what would happen to me once I crossed the border and during the preparations to leave, I had restless nights of imagining the ways things could go very bad.”

Jalalabad is fraught with conflict, and has seen many suicide attacks over recent decades from members of the Taliban, al-Qaeda, and ISIS. Until the withdrawal of American troops in late 2021, Jalalabad airport had operated as a military base for NATO forces in the region.

The goal behind YHJ is largely the same as the Yellow and Blue house in Ukraine, and the original in Sydney: to build and maintain a community of artists. However, beyond the conflict and violence in the region, the conservative culture of Afghanistan is an added obstacle. The central goal of George and Hellen’s return this year was to obtain a completely unrestricted filming permit — the first of its kind — from the Afghan Taliban to shoot their next film.

With the Taliban takeover of security in Jalalabad, it is impossible to film without permission signed and endorsed by various Ministries as well as the police, army and intelligence agencies. It has always been difficult for the pair to film on location, with crowds forming whenever cameras appear, especially when filming women.

This was harrowingly displayed by the threat of violence they faced in filming Love City, Jalalabad. While filming a marketplace scene, the actresses were hurried into their bus when the team was alerted to the threat of a potential suicide bomber. According to George, the Taliban has since greatly increased its presence throughout the city and greatly reduced the risk of attacks such as these.

George was thrilled to eventually receive a permit from the Taliban Authorities. “The [filming permit] means that we don’t have any surveillance, anyone with us, no minders. They trust us to do whatever we like, wherever we go,” George tells us.

George and Hellen’s secondary goal in the region was to ensure that the “Yellow House Arts Centre could be allowed to continue without interference,” requiring George to meet with several senior Taliban members for dinner in August of this year. Impressively, the high-pressure meetings were successful — a testament to the relationships George and Hellen have forged with locals, their standing in the community as artists, and their astute knowledge of Pashtun culture.

Fundamentally, the documentary work they undertake in Afghanistan captures the real work they do to support the community: providing jobs, training film producers and actors and holding school classes.

In a dispatch from Jalalabad in September, George explains that he and Hellen want the Yellow House there to outlive them both, and remain an ongoing cultural centre of learning. He writes: “We see it as the most important contribution we can make as artists, more important than the paintings, films or music.”

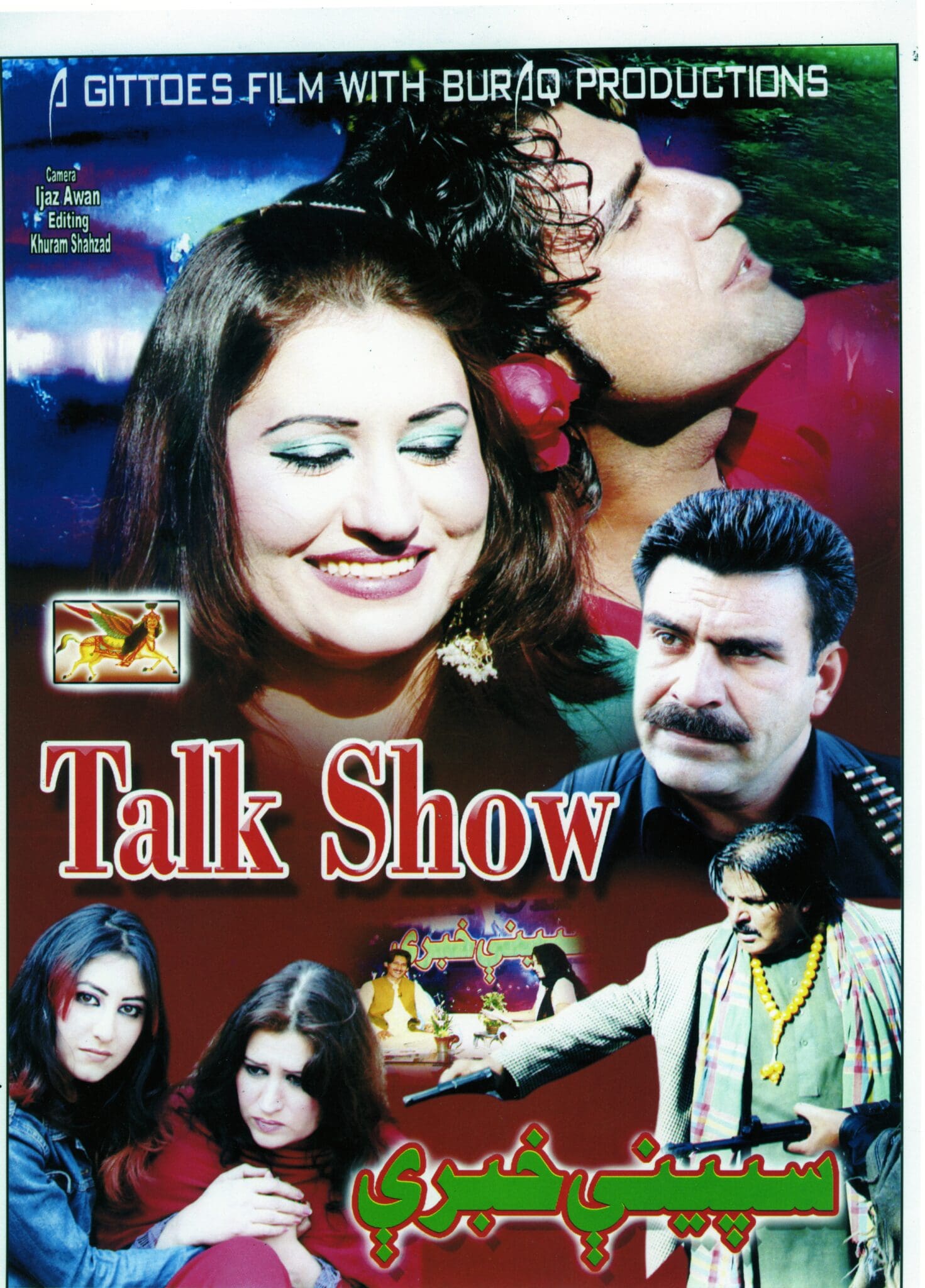

Documentaries are not the only film projects that Hellen and George have produced in Jalalabad; a key facet of their work in the region is creating movies and TV shows for local consumption with the help of their Afghan actor and artist friends and the Yellow House family. All these dramas feature women as lead characters, with scripts that encourage positive social change and greater equality for women.

The pair work hard to ensure these projects are culturally appropriate and have genuine local appeal; the goal is for the films to be organically picked up by residents in DVD stores and their message disseminated.

According to George, their content elevates values of progress and equality: “Everyone in the world would agree that the main social change that has to happen in Afghanistan is the improvement for women.”

A key film in this vein is entitled Talk Show, which follows a woman who is the host of a fictional Oprah-style talk show. Unlike Western talk shows, which often cover celebrity gossip, the narrative is framed around exposing corruption — a value that is shared by the Pashtun community and Taliban, which means that the film does not face the Taliban’s wrath.

The goal of Talk Show is to present an influential woman with agency over her life, who reaches TV screens in local homes, and affects change through representation. All its actors are friends and collaborators of George and Hellen, and the film is now massively popular in the region. Its narratives deliberately mirror reality in Jalalabad’s Pashtun community — corruption, violence toward women, and importantly, love.

Unlike other media produced in Afghanistan, George emphasises that “all the films that we made and are still making feature women; they’re the main characters.”

Supplementing this, Hellen and George train local women to be involved behind the camera and in the director’s chair in order to provide them with opportunities they would otherwise not be afforded.

The pair’s work with women artists extends beyond their inclusion in film, and into creative workshops at the Yellow House and the high-walled Secret Cafe. The latter arose from George and Hellen responding to the needs of creative community leaders: “We had all the best poets and writers and actors and everything in Jalalabad,” George told us.

“I said, ‘So what do you most need?’ And they said, ‘we need a centre with high walls where we can meet.’”

The need for a meeting place for men and women to collaborate is immense. Women are not allowed to meet with men unless accompanied by a male family member, nor are they allowed to be alone in public. George explained that the Secret Cafe was established in order to enable circumstances such as a “lady poet [being able to] go and meet a male publisher and get her poems published.”

Beyond these tangible outcomes of connecting local men and women, Hellen utilises skills from her Gunnery days to run regular workshops for local women. These include physical artmaking projects as well as theatre, music and guided meditation. Speaking to the impact of the meditation workshops, Hellen said that the women were “astounded by the power of their own mind… they’d never done anything like that before.”

While women attending the workshops initially had to be accompanied by male family members, local women are now allowed to attend accompanied only by each other after establishing trust with George and Hellen.

Vitally, Hellen does not perceive these women as victims, nor herself as their saviour. Rather, she suggests that she operates as a provider of opportunities and facilitator of learning. Hellen impressed upon us that despite “living under very difficult circumstances” including constant attacks on their schooling, “these ladies are anything but victims.”

In 2014, during the filming of Love City, Jalalabad, George eschewed tradition by providing the training and tools for a 19-year-old girl, Neha Ali Kahn, to become the first Pashtun woman to direct a local film.

At one point, George and fellow artists working on the film, including Hellen and Neha, were briefly detained in a room of the City Star Hall building. The complex is host to a range of wedding halls, where the team was filming a wedding scene for the conclusion of Love City — part of a series of love-story films that challenged the practice of arranged marriages.

While filming, the artists were detained by the owner of the building who became outraged by the script’s objective. George set down his camera, while Neha continued to secretly film. Upon being asked to hand over his footage, he said “no, I won’t do that… You can get someone to come and shoot me, you can put me in jail if you like but I’m not going to do that.”

Ultimately, George was forced to hand over a number of tapes, including a large chunk of Love City. While distressed that most of the film was confiscated, he was resolute that he made the right decision.

“My responsibility is to get the artists safely home,” he says in the film. The owner was a former Commander in the alliance that had fought against the Taliban. This situation showed George how complex it can be to navigate Pashtun Cultural Laws, particularly those emerging from conservative or ‘tribal customs’.

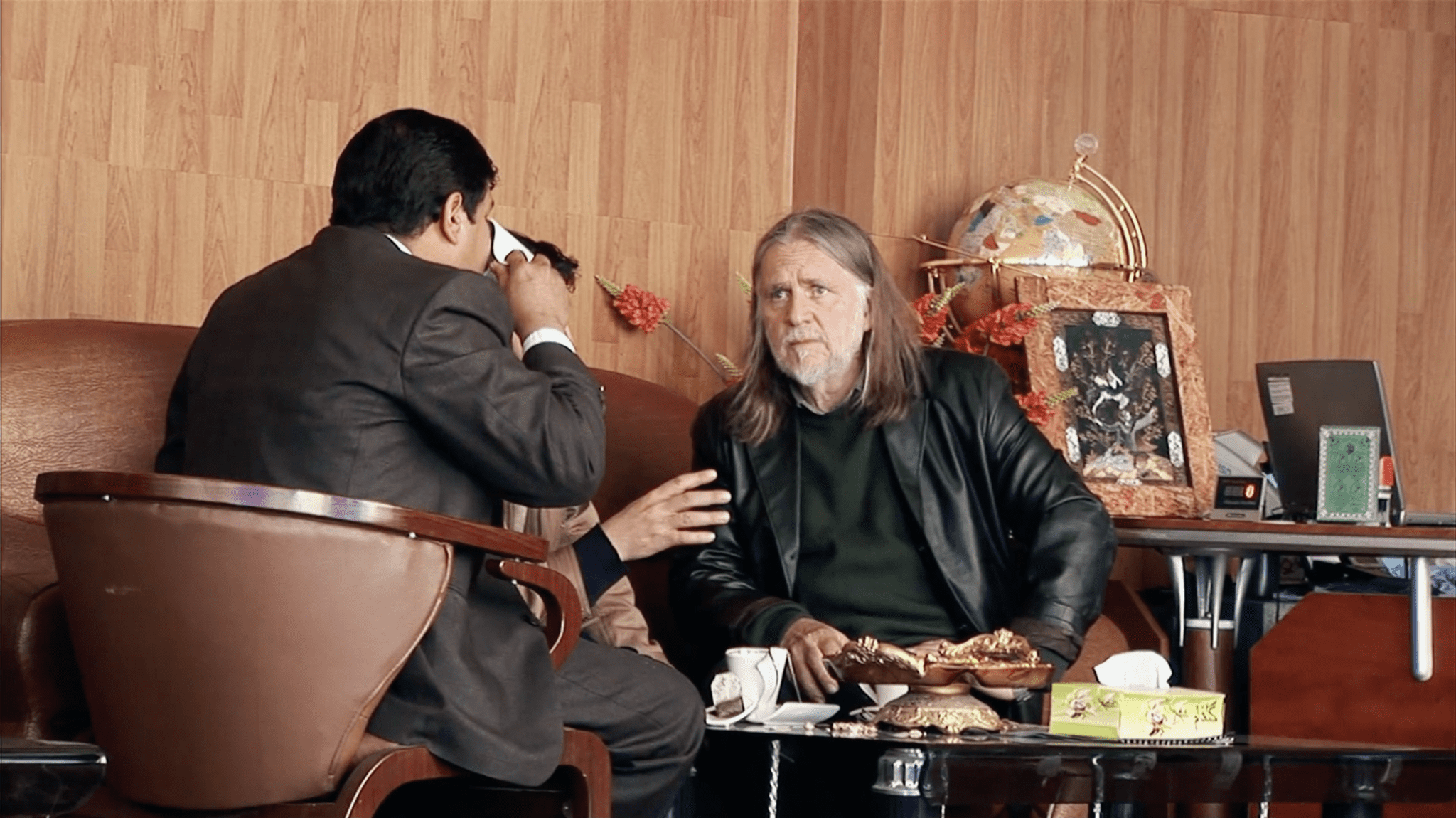

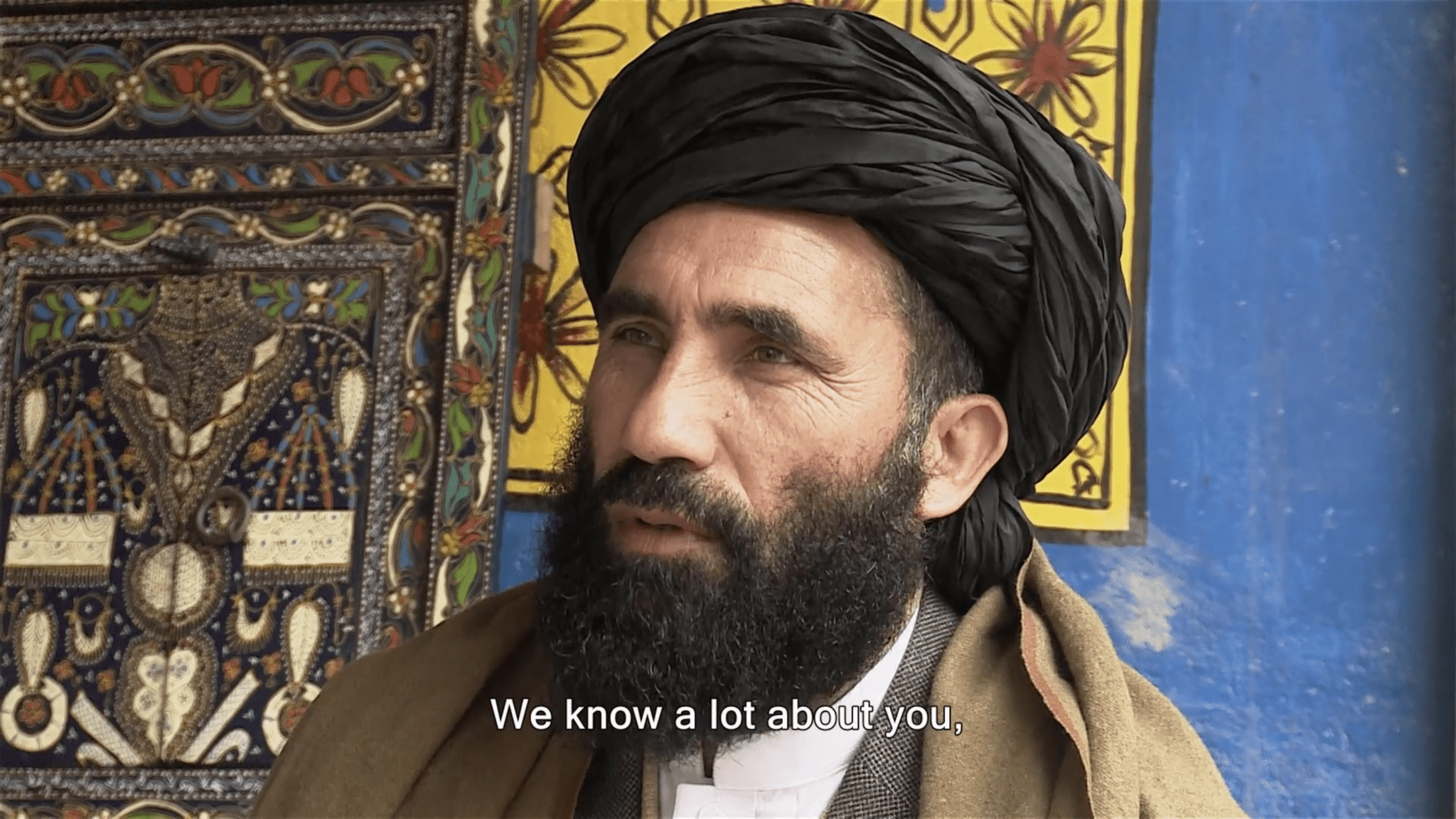

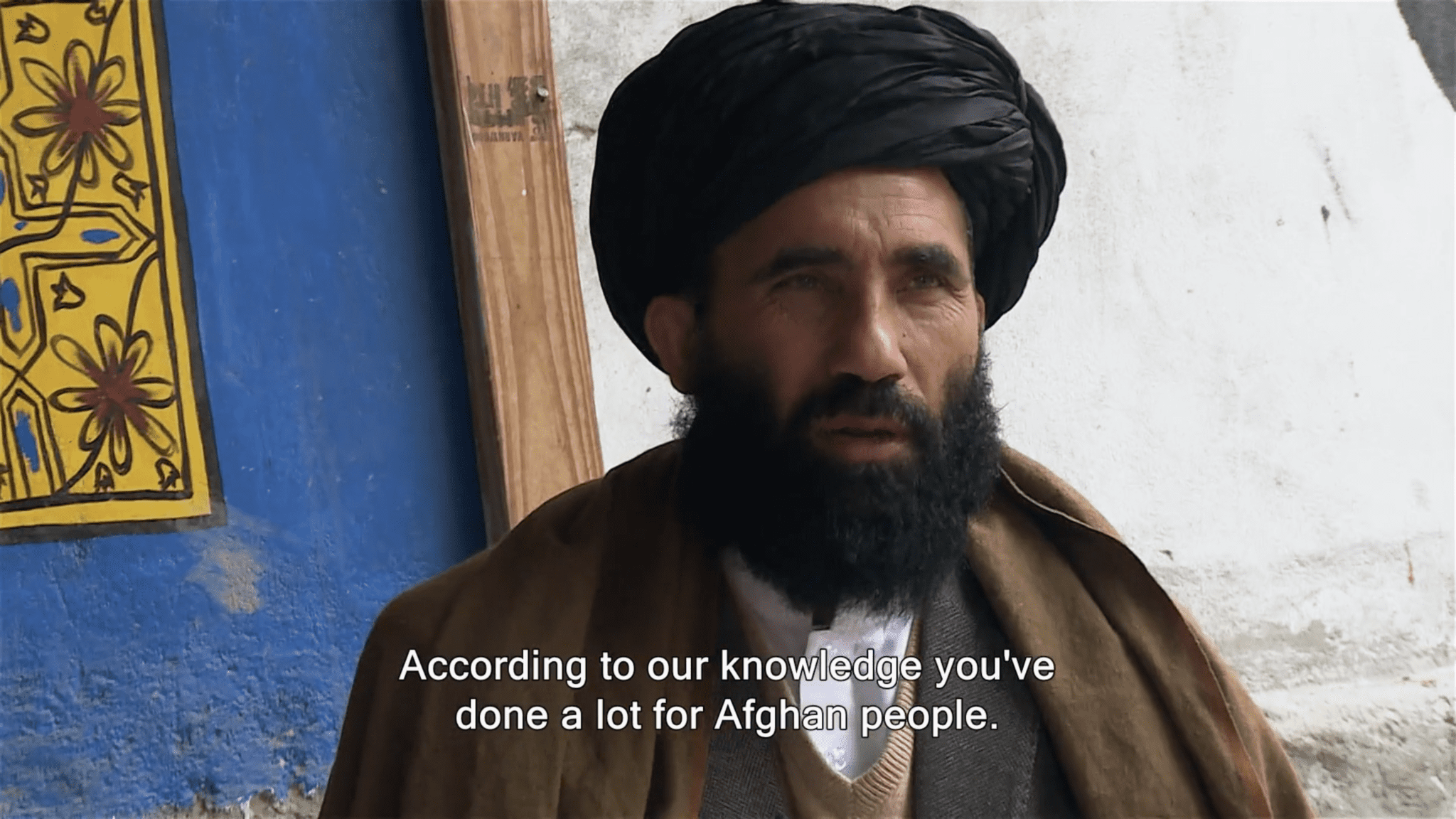

The relationship between Hellen, George and the Taliban continued to develop when the YHJ was paid a visit in 2014 by local Taliban leader at the time, Mullah Haqqani. He arrived at the house with an armed escort to meet with George.

George told us that he and the Yellow House team had “got out the best tea set and the best food and everything. [Haqqani] spent a long while telling us that they’d done a big investigation into us. I thought ‘this doesn’t sound good.’”

“And then at the end he said, ‘we’ve decided that you’re a friend of the Afghan people, and we’re going to give you the umbrella of our protection. And we’ll do everything we can to help you.’”

Above: Mullah Huqqani speaking with George. Screenshots from Snow Monkey, courtesy Gittoes Films and Unicorn Films Melbourne.

Haqqani has since been killed by an ISIS suicide blast. George and Hellen’s work in the region continues regardless, as they forge relationships with new leaders to continue safely operating in Jalalabad.

“I do not see the Taliban through rose-coloured glasses and I am certain they will object to aspects of my film,” George wrote to us in a recent dispatch. “But what I will be attacked for in Australia, [the] US, and Europe is showing them to be human.”

Given their now-productive relationship with the Taliban, though precarious, there is perhaps no limit to what they can achieve in the future, unburdened by the immediate threat of Taliban intervention.

The Taliban’s aforementioned visit to YHJ was captured during the filming of Snow Monkey in 2014, eight years before their unrestricted filming permit was obtained.

The improvement of their relationship had an immediate impact on what the Yellow House team could achieve.

Snow Monkey follows the turmoil of child-gangs in Jalalabad and the exhaustive, frequently dirty labour children must do to survive. The documentary opens on Steel, the leader of a notorious child-gang, and quickly shifts to the comparatively naive boys who sell ice-cream out of little red carts in the scorching Afghan heat. Their carts whir out the front of the Yellow House with a shrill song that comprises the notes of ‘Happy Birthday’ — this is at first is unwelcomed by George, “we’ll pay you to go away”, he says.

The young boys call themselves Wari Shadi (Snow Monkeys) because “monkeys are naughty, we are naughtier,” in their words. They are soon befriended by George, seeking to bring them off the streets and into the circle of the YHJ. George tells them: “This is the Yellow House, a place where weird stuff … can happen and no one’s going to bother you. You can do painting, music, theatre, anything you like — you’re free here.”

George goes one step further and offers them employment and skills training: “We’ve been making movies, Pashtun-language movies, and we want to sell them in Jalalabad…do you think if we gave you some movies to sell as well as [your] ice cream, you could sell DVDs and we could give you a commission?”

The Snow Monkey’s eyes light up with equal parts joy and agreement. “This is just a start for you guys… Maybe you could all be film producers in the future — what’s the future for you guys?” George asks.

In no time at all, the boys sell out of both the DVDs (such as Talk Show and Love City) and their ice cream. Soon they tell George that they want to make a drama movie together about their lives on the streets of Jalalabad, about kids like themselves who go without protection or education and find themselves in spheres of corruption and violence.

“Together we will make a film and show what goes on in this city,” says the eldest. When George asks if he wants to be in the movie, another younger member of the group says:

“I don’t want to plant bombs under bridges, or in mosques. We want school.”

In tandem with training the kids to operate a camera and shooting their movie, George sets up tutoring lessons in the backyard of the YHJ for the Snow Monkeys to catch them up with the education level appropriate for their age. Following this, he successfully gets all eight of them enrolled in regular schooling.

Eight years on from the film, several of the boys, such as Zabi who was Assistant Camera on Snow Monkey, still work closely on film projects with George, and remain in contact with the YHJ.

In a dispatch from October this year, George told us: “We have watched [Zabi] grow from the 12-year-old of Snow Monkey to a handsome and formidable man.”

In the same letter, George also revealed that he reconnected with Steel, who has left the life of gang-related crime behind, and many more members of the YHJ: “I have been overjoyed to see all my friends again in Jalalabad with big hugs and kisses but none have been as thrilled by the reunion as Steel,” he wrote.

Each member of the YHJ who keeps it operating — cooking meals, running workshops, producing Pashtun-language films, keeping children off the street and teaching them new skills — has left an indelible impact on the surrounding community of Jalalabad. George and Hellen have built an ecosystem of creatives within the YHJ that function and exist beyond themselves; they facilitated its creation, but it is the people of Jalalabad who keep it alive.

In the closing scene of Snow Monkey, the city gathers to watch their film projected over a frantic nighttime street, and newly-trained cameraman Zabi remarks: “For a long time Afghans haven’t seen ourselves on TV. Now we can make and watch our own films, and we are very happy”.

Future Work

The stories above comprise just a fraction of George and Hellen’s work across the decades. Gittoes has worked across Nicaragua, the Philippines, Yemen, Somalia, Cambodia, Palestine, South Africa, Western Sahara, Bosnia, East Timor, Congo, Northern Ireland, Iraq, and Englewood in Southside Chicago. George reflects on much of this work in his impressive 2016 autobiography, Blood Mystic.

The artists have been working on editing their Ukrainian and Afghan films-in-progress, with much editing taking place in the Pakistan Yellow House. More recently, George returned to Australia in late September to speak alongside Hellen at the Queensland Art Gallery for the unveiling of Victory Triptych (2022), which he painted on the ground in Ukraine.

The pair have bought a house in Jalalabad, and plan on continuing their work there by setting it up as a new, permanent Yellow House.

George tells us that he is excited to repair it, as “now we’re able to design something, plus we’re not going to rely on power poles, we’re putting in solar.”

Hellen told us that, besides this purchase, “the other surprise is that the Taliban aren’t monsters, they’re human.”

“I’m actually going to be starting up the women’s workshops when I get back. I’m going to be sitting in the head Taliban office, helping them write their [school] syllabus,” she tells us. The previous Afghan syllabus was created by Americans, and reflects the culture of the US rather than Afghanistan. Hellen spent over a decade as a senior secondary school teacher in Australia, and intends to use these skills to empower Afghan youth.

With the war in Ukraine now into its seventh month, and still no end in sight, George tells us that he and Hellen will have to balance their commitments by “jumping between Ukraine and Afghanistan.”

George is adamant that he has an obligation to return to Ukraine: “If [Putin] uses tactical nuclear weapons, I’ll be there the next day.”

When pressed on the danger of this situation, George tells us: “If that happens, I’ve got to be there.”

“That’s what I do. I haven’t got a death wish, but that’s just like someone who studies the Barrier Reef and learns that there’s a new outbreak of Crown of Thorns.”

“They go there to investigate it. That’s my thing, my specialty,” he said.

Despite a life and career based around war, George remains an optimist and does not believe that the conflicts he’s witnessed have no end: “If we can stop wasting money and people on war… we could make this into heaven on Earth.”

George best puts this vision into words in a Ukrainian dispatch.

He writes:

I would love to travel back to all the places I have known in their times of conflict and rent studio spaces where I can paint and Hellen can make her music, in peace. Enjoy the transformation of a world away from war.