I

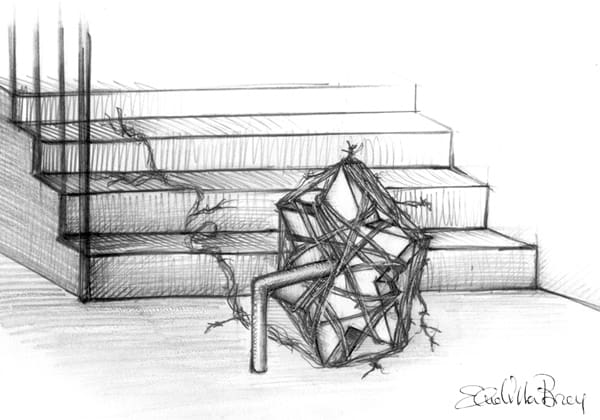

Kafka’s Odradek is a strange creature. He looks like a “flat star-shaped spool for thread” and yet is not, for despite the fact that there are old, broken-off pieces of thread wound on it, a small wooden crossbar sticks out of the middle of the star, which, due to another rod joined to the crossbar at a right angle, allows him to stand upright as if on two legs. Despite his awkward appearance Odradek is nimble and apparently sentient. When asked where he resides, he simply says “no fixed abode.” He laughs without lungs, a sound “like the rustling of falling leaves.” Even his name is ambiguous, whether it comes from the German or the Slavonic is unclear. Kafka’s narrator thinks that it is unlikely that Odradek can die, as everything that dies has a purpose, which Odradek lacks. The thought that Odradek will outlive him is almost a painful one.

Little seems more useless, confusing, or even painful at first glance than reading a text in a language one barely understands. The task is alien to the purpose of reading as it is commonly conceived. Isn’t the point of reading a text to understand it?

I would say no. In fact, I would argue that reading a text in a language of which one has only a rudimentary grasp is an invaluable process. The lack of comprehension itself allows us to appreciate the musicality of the language and escape the arrogance of thinking that every text, or even any text, can be adequately understood. This restores a beautiful strangeness to the written word. Like Odradek, that which we do not understand will outlive us, but this shouldn’t be a painful thought.

II

Ezra Pound provides the following advice to any aspiring poet: “You cannot learn to write by reading English.” This is because the meaning of the words diverts attention from the movement of the language itself. Reading a poem where the meaning is not immediately evident allows you to focus on its rhythmic and musical qualities, the phrase as a constructed sequence of syllables and sounds.

The English speaker can gain a lot, in this sense, from the following stanza from Lorca, even before seeking out the translation.

La luna vino a la Fragua

con su polisón de nardos.

El niño la mira, mira.

El niño la está mirando

It is both instructive and enjoyable to simply read the lines aloud without understanding exactly what they mean, to listen to the way that Lorca plays with rhyme and rhythm and appreciate the words as sound divorced from content.

This instructive capacity is not limited to aspiring poets. Admiring the architecture of a phrase without being distracted by its meaning can also improve one’s writing in prose, as the way that a sentence moves, both internally and within a paragraph, is itself a form of poetry. Taking a step back from the meaning of the words allows their form to come into focus. Further, to borrow from Henry James, it is the form that “takes and holds and preserves substance, saves it from the welter of helpless verbiage that we swim in as in a sea of tasteless tepid pudding.”

The experience of reading something that you only partially understand is, beyond the initial frustration that it causes, also a very enjoyable one. Once you stop looking for the translation of every individual word or phrase and simply allow the sounds to wash over you, it opens up a wholly different enjoyment. The text becomes music. This experience of language, not squashed into meaning but playing out freely in sound, is a beautiful one.

III

Beyond instruction and enjoyment, being confronted with a half-understood text also allows us to escape the tendency to interpret. This is a valuable thing because, as Susan Sontag has argued, there is a modern tendency to consistently reduce works of art to their content, in order to then offer interpretations of that content. In this, we lose the essence of the artwork itself.

Interpretation is, as Sontag notes, a form of translation — A becomes B, B becomes C — the text is brought into our world, into our language by becoming something other than itself. The act of interpretation transforms the text. This process is often a reductive one as the wholeness and at times unsettling strangeness of the work of art is reduced to its content, something more manageable. To know what a text ‘means’ is to bring it into your understanding as something greatly diminished.

Odradek, for example, Kafka’s confusing, meaningless spool of sentient thread, has been interpreted as reflecting Kafka’s personal anxieties, a critique of capitalism, the Jewish tradition, an uncountable array of other things that take one away from the text itself. While these interpretations can be valuable and interesting, the story cannot help but lose something of its fullness in the process. As the priest says to K in The Trial, “You must not pay too much attention to opinions. The written word is unalterable, and opinions are often only an expression of despair.”

I will be the first to admit that the way that I tend to read is by reducing the text to its content. I skim through the pages, identify the central ideas, write some quick notes and then congratulate myself on having ‘understood’ whatever it is that I have read. This cannot happen when reading in a half-understood language.

In setting aside an attempt to know what a text means, even briefly, and allowing it instead to wash over us, we can get away from this dominant approach to reading. This liberates the text from our understanding and interpretations and restores to it an almost mystical quality. It allows us to glimpse what Sontag insists the “earliest experience of art must have been … that it was incantatory, magical … an instrument of ritual.”