Universities, naturally, participate in a global process of exchange and inquiry. The pursuit of knowledge and innovation is not a national pursuit. Academic developments frequently arise from collaboration between researchers of different nationalities and from different institutions. Clearly, universities must be active global citizens and should not shy away from seeking out opportunities for international connection. Being jingoistic about knowledge production is obviously absurd.

But how do we ensure that collaboration is ethical, particularly in a context where concerns about national security within the tertiary education sector abound?

Regulation of academic research in light of fears of foreign interference is on the rise. The University Foreign Interference Taskforce was established in 2019 to safeguard against it. A parliamentary inquiry into national security risks within research concluded earlier this year. Since 2019, the USyd bureaucracy has included the Research Risk Advisory Committee (RRAC) to assist in ensuring research partners of the University align with its values and legal obligations.

In the midst of this, concerns for academic freedom are growing. Anti-espionage laws could see academics in legal trouble if critical research towards Australia’s intelligence and military activities reaches foreign colleagues or international students. Attempts to prevent foreign interference could constrict academic research — for example, even anonymous survey results, which theoretically could include responses from foreign actors, could fall within the purview of national security laws. Foreign interference laws directly bring universities and their research approval processes into contact with Australian defence and intelligence institutions like ASIO — see the Foreign Interference Bill 2020, for example.

So, academics are subject to increasing impositions — in some cases, direct oversight — on their research activities. Where is University management in all this?

Our interest piqued by former Vice-Chancellor Michael Spence’s expenses for a ‘Chinese navy function’, Honi requested information on all meetings between senior management and foreign government or military officials between 2018 and the present. A total of 45 meetings were disclosed to us, with the bulk of those involving either the Vice-Chancellor or the Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Research).

The majority of these appeared to be fairly anodyne relationship-building with some of the largest sources of USyd’s international student population – 22 of the 45 meetings were with representatives of China. Some of those were with delegates from the Chinese Ministry of Education. Similarly, in 2020, Spence zoomed with the Indian High Commissioner to discuss India’s national education policy. Upon his ascension to the Vice-Chancellorship, Mark Scott participated in meet-and-greets with both the Chinese and Indian consulates, which tracks with the nations’ importance in Australia’s education sector. There are also a variety of cultural meetings: Chinese New Year celebrations in 2019, a meeting with the Duke and Duchess of Sussex Harry and Meghan in 2018, assorted dinners with diplomats.

A University spokesperson told Honi: “University leadership often meet external visitors or officials in order to promote the University’s capacity for research and teaching to generate leads for potential partnerships – including some that can contribute to national, regional and global security.”

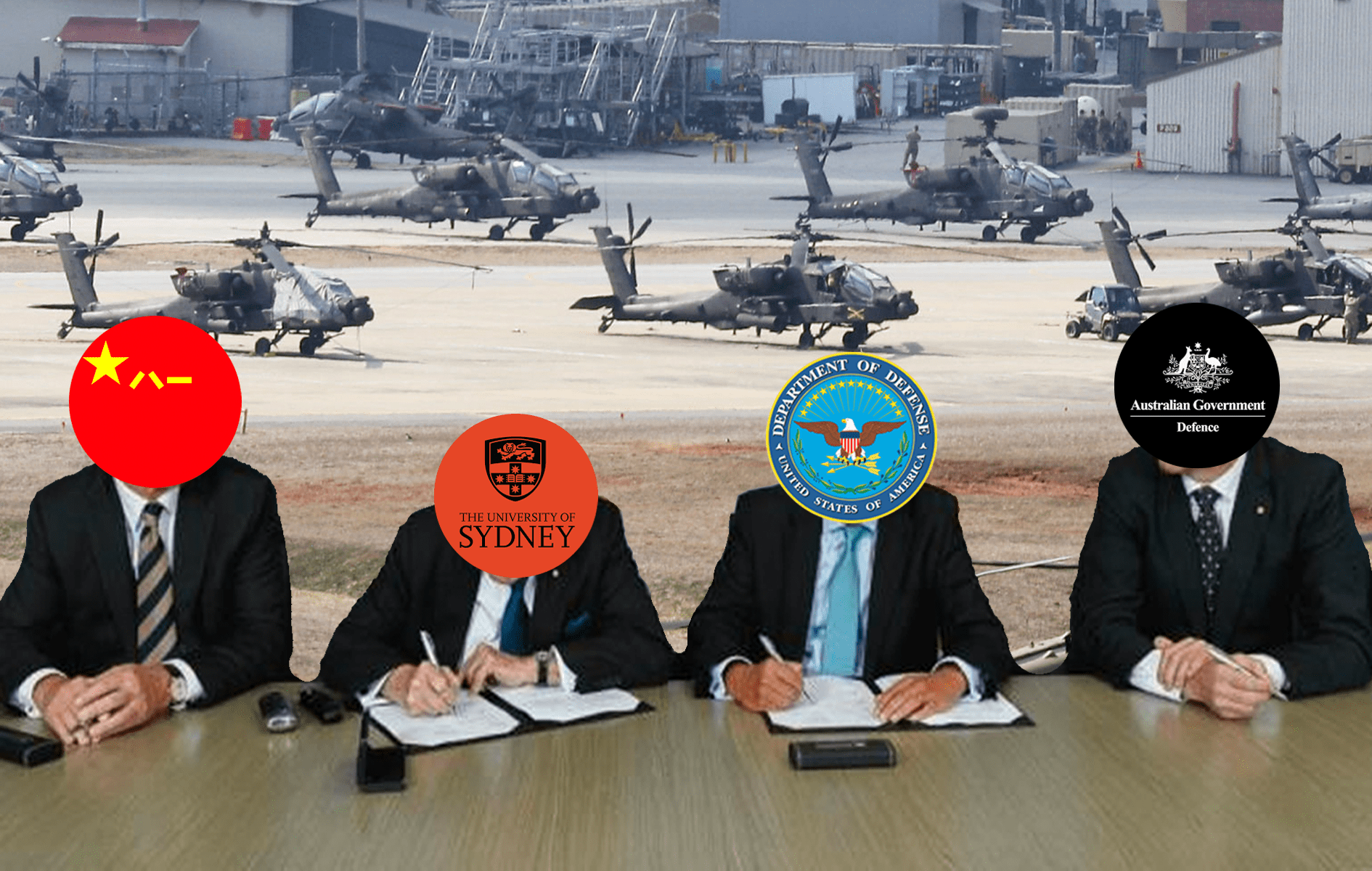

The University’s international engagement doesn’t stop there. University managers met on a number of occasions with foreign military officials. The aforementioned Chinese Navy Function remains unexplained, along with a number of meetings with United States military organisations.

In July, Scott met with officials from the US Department of Defense to discuss “research collaboration opportunities”. In May, Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Education) Duncan Ivison met with a delegation from the US Office of Secretary for Defense (OSD) and Australia’s Defence Science and Technology Group (DSTG).

The University did not comment on the specific research opportunities that were discussed, but told Honi that the University seeks collaboration “in line with all relevant Australian laws and government guidelines, and with the University’s objectives, values and policies.”

These meetings raise questions about USyd’s involvement in defence research. While Australia’s national security laws are stringent, they apply where there is tension between research and strategic goals, but it is less clear how we can ensure transparency when we are collaborating with our allies. Interestingly, the University explicitly prohibits collaboration with tobacco companies, but makes no comparative exclusions for other potentially ethically problematic activities.

Academics have suggested that strengthening our institutions is crucial to navigating the complexities of international ties and military research. NTEU Vice-President (Academic) and lecturer in modern Chinese history David Brophy argues in his book China Panic that so many of the threats of national interference stem from the erosion of the core of the University. Where universities are properly funded and democratically run, the risks of making unacceptable trade–offs will be lessened.