If you’ve walked through Victoria Park recently, you’ve likely noticed the concerningly murky appearance of Lake Northam. The once shimmering, viridescent body of water that lays just a stone’s throw away from USyd’s Camperdown campus now paints a much uglier picture.

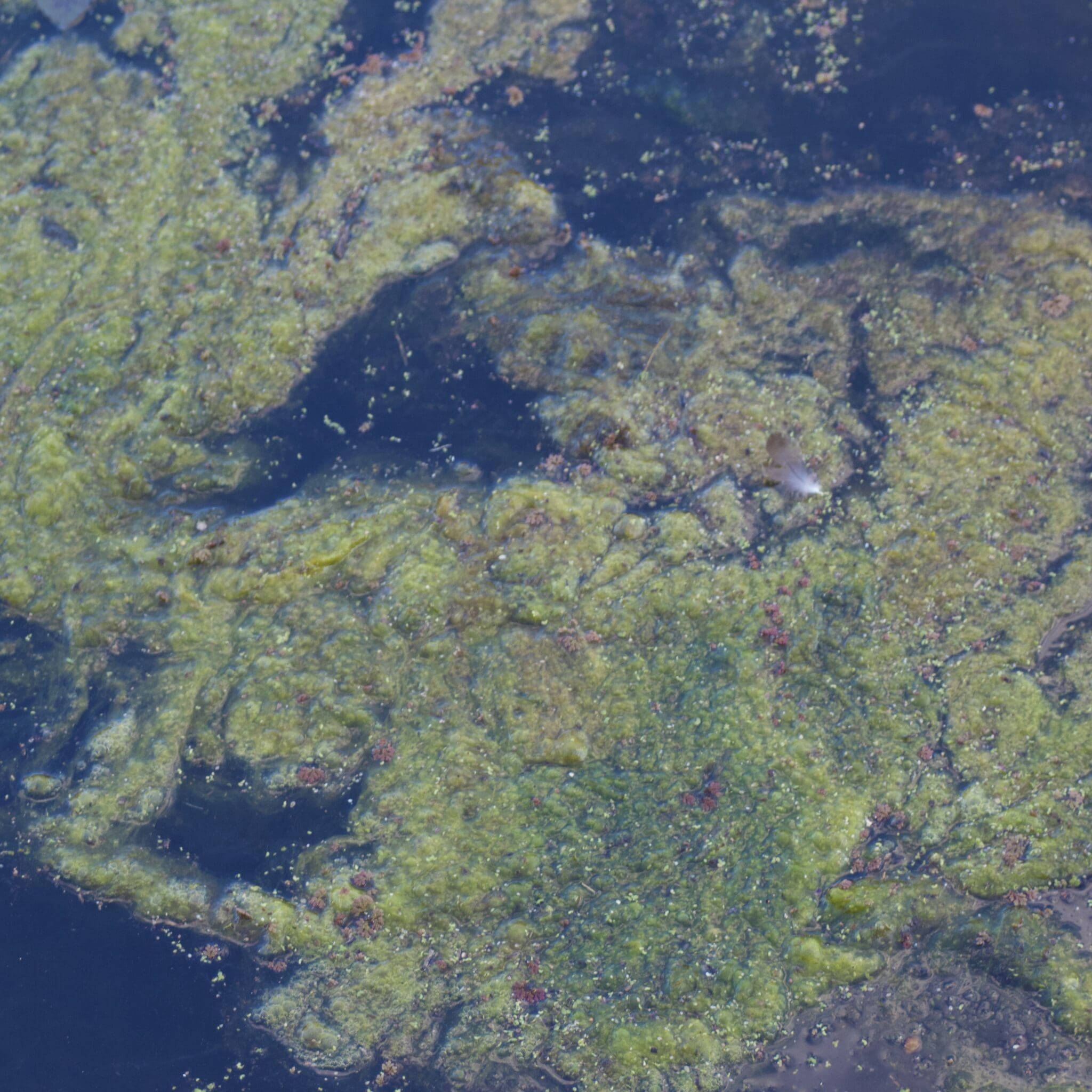

At a quick glance, mounds of entangled, decaying plant matter have risen to nearly wholly cover the lake’s surface. Muddy water is observable in parts, and sometimes aquatic birds appear stuck between it all. It is also not uncommon to see plastic bags, soft drink cans, takeaway food containers, and general rubbish semi-submerged within or beneath the water.

This calls into question the commitment of those responsible for the lake’s maintenance. However, I’m no lake ecologist, nor an expert in aquatic affairs, so perhaps there is more to this story than meets the untrained eye.

Firstly, Lake Northam was officially named in the 1960s, but it was once a part of a tidal watercourse called Blackwattle Creek, which stemmed out from Glebe and constituted a significant area of land inhabited by Aboriginal peoples prior to colonisation.

Lake Northam was the product of a diversion of the watercourse underground, which followed the advance of Western industry along Sydney’s coastline and local urban development. Over its lifetime in Victoria Park, the lake has undergone a series of man-made developments to form its current walled, structured shape in order for aquatic plants to grow, and water circulation systems to be installed.

After first noticing the lake’s visual decline in Semester 1 of this year, I’ve become somewhat invested in its affairs. Since it is man-made, who is responsible for its maintenance? How often does it get cleaned? Why is it full of rotting plants? What constitutes a ‘healthy’ lake, and is it being monitored? To the layman’s eye, the lake looks bad and I wanted to know why.

Honi received word from WIRES and Sydney Wildlife rescuer Michael Goldberg back in April, who echoed my concerns for the lake’s welfare. He explained that he had observed “many aquatic plants turned into mulch and the whole area by-and-large becoming a muddy swamp,” he also noted “a half-submerged shopping trolley”.

Reportedly, Goldberg made several attempts to contact the City of Sydney Council (CSC) and the Park’s coordinator to no avail. Instead he received a call from landscaping contractors Skyline Maintenance Services, who purportedly “look after” the park on behalf of the council. Against concerns that water levels were dangerously low and muddy, Goldberg was told the lake was ‘overflowing’.

The history of water levels in the lake is mixed. In 2017, the lake was drained and refurbished (not for the first time) with new aquatic plants installed, and in 2018 further improvements were made. This included installing “two new stormwater traps and a new recirculation system which has improved water quality,” according to a City of Sydney spokesperson.

The Council further explained to Honi that the project “enhanced the stormwater flow from King street,” which has since supported the health of the lake. I hate to imagine what King Street runoff looks like.

However, it is clear something has radically changed in the lake’s health. Goldberg told Honi that, as a result of heavy rainfall across the state, “the water level has risen slightly, but there are still mounds of rotting vegetation,” and this is widely observable. Why then, given refurbishments in the not-so-distant past, is the lake appearing to suffer?

Honi spoke with a City of Sydney spokesperson about the apparent mass death of the aquatic plants and, initially, they appeared bemused at the assertion that there was anything wrong with the lake at all. Not a great start. However, in a later email the spokesperson explained that the lake’s newly muddy appearance is apparently part of a conscious choice by the Council, stating that:

“Recent heavy rainfall has presented opportunities to further support the flora and fauna that use the lake. Excess sediment was removed in May this year and, on the advice of expert staff at the City of Sydney, some of the sediment was left in place to act as mudflats as there were a variety of wading birds using the area for foraging.”

This explanation suggests that the body of water is now being treated as a hybrid between lake and mudflat — to better support the plants and animals living there — happily allowed by coincidentally heavy rains washing in silt. The lead-up to this outcome is somewhat unclear: If the lake’s wildlife needed a habitat closer to that of a mudflat, why was it only facilitated by accidental rains? On the flipside, what are the consequences of additional storm-water sediment to the pre-existing ecosystem?

Notably, the Council expressed the importance of mudflats because this type of ecosystem has disappeared from Sydney “due to urbanisation and the dredging of rivers and creeks.”

The Council told Honi that “Leaving mudflats in place greatly benefits the remaining population of birds, frogs and macroinvertebrates that rely on this type of habitat”. This leaves it unclear as to whether the Council intentionally made the mudflat or simply allowed it to exist.

On an information panel next to the lake, the new management system reportedly utilises the mudflat and reeds as a means to absorb the pollutants out of stormwater. It is described as a “newly constructed wetland and bioretention system designed to improve water quality.”

With the muddy waters somewhat cleared, the topic of decaying plant matter is unavoidable. Roots, leaves, and chunks of aquatic plants appear across the lake’s surface, entangled with duckweed. The Council expressed that despite it being visually unappealing at times, the “decaying organic matter is important for the lake’s ecosystem as it provides food for smaller water bugs which are then eaten by larger insects who in turn become food for some water birds.” While this admittedly makes sense, I have personally never observed this magnitude of decaying matter in the lake before. In fact, every other person that I asked said they had never seen it this bad before — except one local resident, who noted that it had only looked markedly worse before major refurbishing in the mid 2010s.

Worryingly, when plants decay and die, they release their stored nutrients back into the environment, particularly nitrogen. When large-scale decay occurs, large quantities of nitrogen and nutrients enter the surrounding landscape, and, in this case, the lake. A potential outcome of this process, called eutrophication, is blue-green algal bloom developing thanks to overly nutrient-rich water. Eutrophic events are caused by several other additional factors, including change in water turbidity, intensive nearby agriculture, fertiliser runoff, and surrounding industrial activity. None of these factors are unimaginable for a lake in the Sydney CBD.

Again, I’m no expert, but it certainly appears as though this type of algal bloom is beginning to take hold in Lake Northam. Long, green strands of algae appear across sections of the surface which, to my best semi-educated guess, is a form of the green alga Cladophora based on Water NSW’s guide to identifying algal blooms.

Large quantities of harmful algal blooms can be toxic to animals, and mass blooms can also cause a ‘dead zone’ in the ecosystem. According to National Geographic, these zones are caused when blooms are so extensive that they “prevent light from penetrating the water’s surface”, and additionally “prevent oxygen from being absorbed by organisms beneath them.” Lake Northam is yet to reach this point, but the frequency at which it is being monitored for such biological events is unclear.

According to a Council spokesperson, their staff “work closely with contractors to maintain the park and lake removing rubbish and advising of any other issues that may need to be addressed.” Admittedly, my faith in this statement is shaky at best. One has only to do a cursory walk around the lake’s edge to see numerous cups, cans, plastic bags, and fast-food containers at the bottom of the lake. All of the litter present appears visibly aged — these are not objects that have blown in between inspections by contractors Skyline Maintenance Services, but instead have remained in place for sometime.

Michael Goldberg told Honi that he observed a submerged, rusting bike and several footballs stuck in mud. At the time of writing, there are at least dozens of visible items of rubbish in the lake.

At best, if the lake’s decaying plant matter is indeed a part of its healthy ecosystem, the mudflat is effectively filtering stormwater, and the algal bloom isn’t as bad as it appears, one thing can be said for certain — the lake is full of micro and macro plastics.

In this regard alone, the lake is in dire need of attention. I encourage students to walk down to the lake and judge for yourselves.

In an ideal world, this article has a follow-up with an expert academic who can explain the ecosystem and conduct tests on the lake’s water. Until then, here is my best guess at the chemical makeup of the lake:

30% fast-food-derived micro plastics, 17% toxic industrial runoff, 21% vape liquid and other drugs, 3% toenails, 24% angrily-thrown discarded copies of Honi Soit, and 6% cigarette ash.

Photography by Thomas Sargeant, September 2022.