Whiteness is so ingrained in our everyday lives that it is seen as ‘normal’. Everything around us reflects whiteness, including what we listen to, watch, and read. When I was younger, I wished I was ‘normal’ (read: white) because I assumed it was the default.

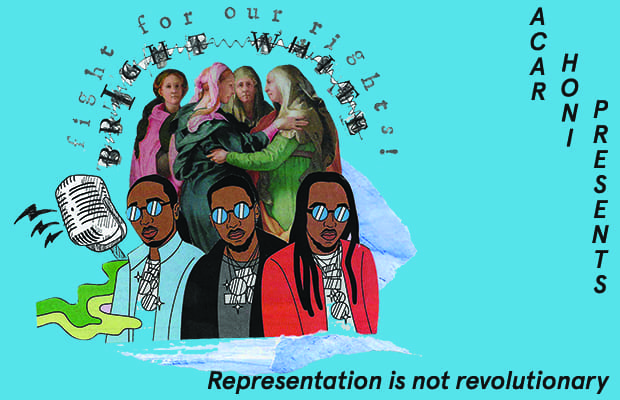

Representation can be a relief from everyday whiteness and can provide a critical and necessary voice for people of colour, but it is hardly a revolutionary concept. In fact, it is the bare minimum.

It is important to consider that representation is a two-way street. Positive representation certainly exists, but so does negative representation and fictional works can play such a large part in how we conceptualise the world and people around us. In Orientalism, Edward Said talks about the ‘Orient’, also known as the Global South, existing in the European cultural imaginary as an uncivilised and inferior “Other” that exists in contrast to the civilised West.

Western representations of people of colour in film, television, theatre, art and literature has historically involved the use of dehumanising and exaggerated caricatures. Take minstrel blackface, for example. It was popular amongst white people in the 1800s and involved white people dressing up as African-Americans and imitating them in a way that depicted them through degrading stereotypes. It was also popular amongst white Australians who dressed up in blackface as a way of mimicking Aboriginal people.

Contemporary campaigns surrounding the issue of representation have been focused on positive representation of ethnic minorities on television and in film. However, the definition of what good representation looks like differs from person to person, from community to community.

I can’t speak for other communities, but representations of my own (Palestinian, Arab, Muslim) communities are rarely done well, if at all. Arabs and Muslims have typically been represented through the white lens as terrorists, backwards, and barbaric. When they are portrayed neutrally or positively, it is often in a tokenizing way that doesn’t address their background. They are used as a plot device to advance the white character’s main story, or are one-dimensional characters that lack nuance and resort to tropes.

The show Community is a good example of when white writers try to write Black and Brown characters. For example, Abed is a twenty-something Palestinian-Polish community college student who is played by Indian-American actor Danny Pudi (because we all know Brown people are interchangeable!). In the show, his heritage is rarely addressed in a meaningful manner and is rarely handled with care. Even in the episode when we meet his family, his dad is played by a Pakistani-American actor and his cousin is portrayed as a woman who wears the niqab even though the majority of Muslim women do not wear it. They pretend to speak Arabic which sounds like gibberish. Although Abed’s portrayal itself is not really negative, it is clear that there is still work to be done there.

Representation is often done best when we tell and write our own stories. Randa Abdel-Fattah’s books are a great example of this. She approaches the Arab-Australian experience through her characters in a nuanced way that leaves room for diverse narratives and fully-fleshed out characters with agency that aren’t merely reductive stereotypes.

Even when we approach representation in “real life” such as in the news media or in politics, it merely is a tool for navigating whiteness and not the be-all-and-end-all.

Waleed Aly is a critical Muslim voice in the media especially surrounding issues of racism, Islam, and Islamophobia. However, one or two or even three Brown, Black, and Indigenous voices do not change the fact that Australian media is overwhelmingly white and impacts the narratives that are filtered through.

Essentially, representation works as a platform. Who gets to represent our stories and how they get to tell them also depends on who has access to social and financial capital to be the face of, or even make those stories come to life. Many people of colour write their own stories, but often when our stories are not written by us, we get a one-dimensional view of what our experiences look like. Perhaps, even a person of colour that fits the ideal definition of the “model minority”.

Even on a political stage, we see people of colour entering politics on federal, state, and local levels. On one hand, it is refreshing to see people of colour bringing their experiences and knowledge to an institution that is very white and very male. On the other hand, Australia remains a settler-colonial state that has committed and continues to commit atrocities against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in this country. Even if, hypothetically speaking, a person of colour rose to the top and became Prime Minister, it does not change the fact that whiteness is deeply woven into the fabric of this country. It will take more than a Brown or a Black face to undo 200+ years of colonisation.

While representation can be a force for good, it is hardly revolutionary or liberating. It is the result of people of colour playing catch-up in white-dominated industries and institutions. It is normalising what should already be normal.

“I really hate the word ‘diversity,’ it suggests something…other. As if it is something…special. Or rare. As if there is something unusual about telling stories involving women and people of color and LGBTQ characters on TV.” – Shonda Rhimes