Honi Soit prides itself on centuries of radical, counter-cultural, rebellious politics. Always pushing the envelope, sometimes we have to interrogate the definition of radicalism and how it supported various students in Honi’s many epochs. When a paper of this stature and legacy has existed throughout decades of inequalities in the print and media industries, we owe students a rigorous, revisionist examination of glorified Honis past to better understand the paper we hold in our hands today.

Enter the women of 2024’s Honi. Limited by archival lacuna, we can only dip our toes into the pernicious sea of sexism that has shaped Honi’s coverage of women’s issues and female participation in the paper over the years. Regardless, come with us as we take to the decades to nudge the skeletons in the closet, from the fringe of Honi’s birth to this present moment.

Dismantling whose master’s house?: 1930s and 1940s

Honi came to be with a bang in 1929, typifying an anti-establishmentarian student voice. However, although these years of Honi are glorified now as times of radical upheaval, the embryonic rag was still chained to sexist social mores.

Honi was viewed as a paper of progressive politics and rebellion, but entrusted in the hands of privileged white men. The paper had sole or few chief editors throughout the 1930s and 1940s, and the lineup was wholly male until 1943, when Emily Rossell edited the paper for four months. However, in the late 40s, teams of sub-editors often included women, working under the helm of a male chief editor. Regardless, the role of an Honi editor or sub-editor appears distinct from our understanding of the breed today — the pages of Honis from the 1930s and 1940s mostly involve a collation of reviews of student society events, guides to future events and letters; these pieces are barely editorialised compared to the process of pitch filtering undertaken by 21st century editors. Hence, there is less opportunity to gauge the editors’ opinions.

Honi’s reportage on women’s issues was largely influenced by gendered divisions in student unionism. Our modern University of Sydney Union was cleaved into Women’s and Men’s Associations, sequestering women’s issues out of the spotlight. The entrenched gendered separations are evident in the synecdoches used to describe the unions; after a debate between the Men’s and Women’s Union, the headline “WOMEN DEFEAT MEN” was emblazoned on the paper’s front page.

Honi also proffered the Women’s Union President a small slice of the page to relay any organisational updates. Honi’s coverage of women’s issues also revolved around colleges, such as rundowns of debates between representatives from Sancta Sophia College and the Women’s Union, and sporting clubs.

The ways in which Honi wrote about women predictably mirror the extremely misogynistic era in which it was created. The paper reveals some awareness of the inequality between men and women at university, but typically indicts qualities of female university students for this. A 1930 letter to the editor complains that Sydney University women are “the most uninteresting, unintelligent and undressed aggregation of present-day females,” denouncing their proclivity to study and attend lectures rather than party. This discourse is unsurprising, but does subvert the glorified narrative that Honi was born in an utopia of progressive politics. It poses the need for a reformed view — that Honi was a ‘radical’ student newspaper, but only served the privileged male student.

Cunterculture: 1950s and 1960s

Honi in the 1950s continued much in the same vein as in the 1930s and 1940s in terms of content and reporting. While 1952 and 1954 saw two female editors-in-chief, Meg Cox and Marie Burns respectively, this did not drastically change the misogynistic undertones of articles that were produced. Many student organisations were still split on gendered lines and reported on separately, in a clinical manner that does not give great insight into women’s participation in Honi.

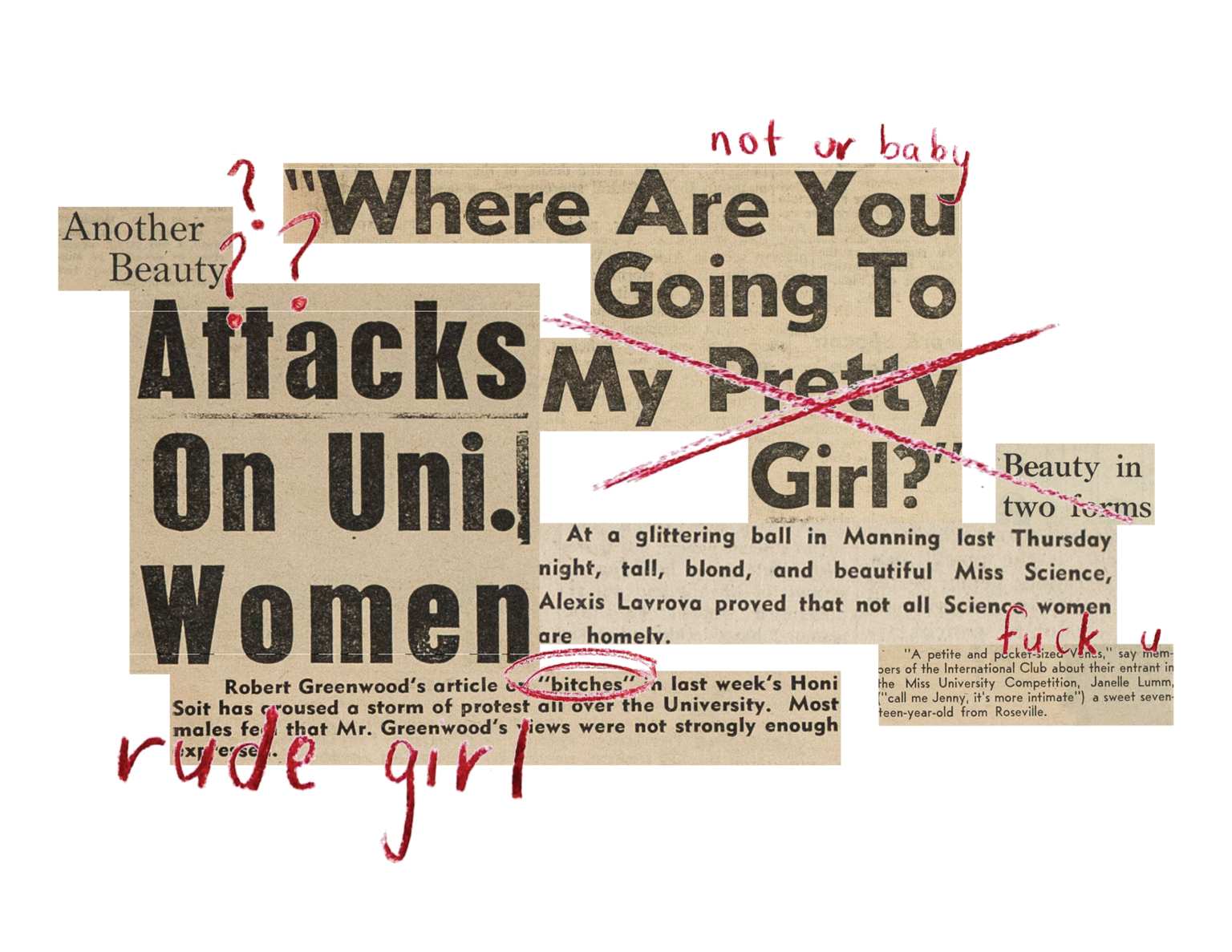

Glimpses of progress in feminist politics were overshadowed by incidents that are flabbergastingly misogynistic to the modern reader. In Honi, sportswomen and ‘comediennes’ were platformed, but highly subject to male perspective and the male gaze. Female students were frequently referred to in headlines as “women students,” the noun prefix distinguishing them from male students — the University and the paper’s target audience. Apart from their societal involvement, reporting on women at USyd took the form of sweeping generalisations; a published opinion that “All the girls like Union Night because of all the handsome men they find there” does not stand out in a sea of phrases that sought to pigeonhole female students in various unsavoury depictions.

Alongside the sunset of the 1940s rose a concerning competition which dominated Honi coverage for almost a score. Miss University competitions were organised every year to raise money for the World University Service, with USyd expected to submit a USyd candidate to the Miss Australia Quest. A 1949 Honi calls out for “BRAINS AND BEAUTY”, setting the tone for the objectifying nature of the competition. Societies were eligible to sponsor candidates, and the winner was crowned at the “Recovery Ball” in addition to receiving a “magnificent Innoxa beauty set.” Many Honi front pages from the 1960s are marked by candidate photos.

The famed ‘Sydney Push’ of the 1960s and 1970s influenced Honi to shift gear into more political coverage. It must be remembered, however, that this movement received most of its momentum from larrikin and male-oriented groups. In revisionist history, it has been subject to rigorous feminist criticism of the sexism entrenched in these groups, which prohibited substantial female inclusion. The politics of Honi’s famed 1960s contributions to discourse are therefore darkened by this exclusion.

Flower power and institutional change: 1970s and 1980s

The women who edited Honi in the 1970s and 1980s share a strong affinity with the arts: their recent achievements in film, photography, literature and theatre are a testament to their radical visions for the paper. Star-studded with front covers of “rude girls” and the regularisation of Women’s Honi year after year, these two decades were defined by a strong tension between feelings of gender equality in the editors’ personal lives, and the wider culture of misogyny they experienced in student politics.

Award-winning film producer Penelope McDonald, along with author, screenwriter and Cannes-nominated director Julia Leigh both highlighted these themes in their separate interviews with this year’s women of Honi. Despite editing a decade apart – in 1978 and 1989, respectively – both explored how their love for the paper tempered the discrimination they encountered.

When asked about their relationships with the men on their team, both recounted that they “were not misogynistic,” and that they “were very close,” citing that they “worked well together.” For Penelope, this amounted to feeling “equally powerful to males,” while for Julia, it manifested in collectively putting a “portion of our small stipend towards a ‘kitty’ which we’d spend on a group dinner at the same Indonesian restaurant on King St each Sunday.” Today, Julia cherishes “all my fellow editors like family.”

Nonetheless, sexism continued to be a common experience of editing Honi throughout the 1970s and 1980s. In 1978, Penelope and the ticket “collectively decided not to accept a full page ad for a motorbike, if my memory serves me correctly it was Honda, as it depicted a woman in a provocative semi-naked position biting into an apple astride a motorbike. It was worth a lot of revenue to us, and we had to justify the non acceptance to the SRC.” Tony Abbott, the SRC President at the time, was reportedly the hardest to convince. As Penelope puts it, Abbott was “difficult to work with and was in my view misogynist. [sic]”

Just as Penelope felt misogyny was “in the infrastructure of the university as there was, and is, in society”, Julia noted that “misogyny was in the air we breathed” – with present-day federal Minister of Industrial Relations Tony Burke “frequently lingering in the corridor.”

She recounted her experience editing Hermes on the Union’s Publications Committee after her time at Honi, where women were undoubtedly a minority. After successfully leading the introduction of “a quota so that of the three editorial positions, one would go to a woman” at Hermes, the Committee “voted to appoint three men” in the same year, ignoring the women shortlisted to become editors by arguing that “the quota had not come into effect.” Julia felt, as we did reading this anecdote, “so angry and frustrated.”

But this work speaks to a broader commitment to resistance and radicalism shared by the women who have shaped Honi’s legacy. While women’s rights “were in the forefront of our minds” on Penelope’s team, Julia’s group “did a special Women’s Issue and also sought to regularly cover ‘women’s issues.’” This included “equal pay for equal work” and “women’s rights over their bodies” in 1978, progressing to the institution of a rotating roster for the position of ‘Co-ordinating Editor” by 1989. Not only did Honi cement its reputation for provocatively feminist content during this time, but its women editors were at the forefront of leading institutional change.

Noughties and naughties: 1990s-2000s

Honi’s first issue of the 1990s saw the incorporation of “Womyn’s space” as a weekly feature. Intended to increase women’s input throughout the entire paper, the only stipulation was that the authors were women. The spelling of “womyn” was used to counter the Western cultural assumption that men are the ‘norm’, which has long been reflected in spelling. The following issue published a letter where Steven claimed the space was “discriminating” against men and barring them from contributing. He decried that contributors “cannot be a female and [also] not be a female”, arguing in favour of a non-segregated space profiling gender politics. This resulted in back-and-forth responses across issues; Liz Wilson argued against Steven’s propositions, and support for Steven came in the form of the Feminists Against Ball-Biting Feminists (F.A.B.B.F). Steven was nowhere to be found. The frequency of letters in response to the womyn’s space articles increased soon after.

Writer, editor and researcher Catriona Menzies-Pike spoke about editing Xpress for Honi (1999) alongside a 14-member team: seven men and seven women. Politics were nonuniform, with a varied spectrum of feminism frequently influencing debates on the language and representation of gender. As a student, Catriona was inclined to condemn many arguments made by colleagues as sexist. However, after decades-worth of employment across media, arts organisations and universities, she came to realise that the Honi experience was unusual in that there was the freedom and space for extensive discussion.

She also spoke about her pride in contributing to the “staunch tradition of feminist journalism at Honi Soit” while acknowledging the lack of intersectionality or attention to queer and trans politics.

Journalists Rima Sabina Aouf (2006) and Kate Leaver (2008) also described Honi Soit of the noughties. Rima’s 2006 team was “almost a fully cross-factional ticket… apart from the Young Liberals.” She characterised her colleagues as progressive and politically aware, ranging from Broad Left women and Labor Left to centrist/Labor Right/college men who had worked on the defunct Union Recorder (predecessor to BULL and PULP) in addition to SUDS and Arts students. She maintained that the male editors did not need policing, especially when responding to calls for a “men’s edition to match the annual women’s edition.”

The 2000s continued the trend of misogynistic letters handed in via email. Platformed on the letters page and not the “paper proper”, were suggestions that women walk confidently to prevent sexual assault and messages like, “I would like to apologise to all women for my sex drive… Now back to the cricket.” Rima noted one major editor’s debrief after an article by the name of “An Idiot’s Guide to the United Nations”, where derogatory jokes about Monica Lewinsky made it to print.

This decade favoured shock humour, and Rima acknowledged that this sometimes involved insensitive and ableist jokes. Intersectionality, including gender diversity and trans perspectives, was not duly considered, and even though Rima was a person of colour, she did not identify as one at the time. Honi’s coverage of Muslims close to the 2006 Hezbollah-Israel War was deemed racist by the Socialist Alternative (SAlt), and they trashed the Honi office in retaliation.

Rima also echoed the sentiment that the Honi and SRC spaces were safer compared to overall campus environment, especially being an activist who leafleted. Rima concluded that female or gender diverse editors are more likely to face heightened abuse due to stronger influence of the manosphere.

Kate spoke to her experience, saying that she did not face misogyny amongst a team of five men and five women, where mutual respect and close friendships flourished. This was evident in her ability to joke that the final comedy issue was “written by two of the men” who were self-appointed and that it had “a whiff of ‘can women be funny’ to it”.

Regarding the women’s issue of Honi, Kate admitted to wanting to get on a lecture theatre desk and roar that “EVERY ISSUE IS A WOMEN’S ISSUE.” She fondly remembered how her article on male colleges and misogyny earned her a lifetime ban from a bar, indicating that the rampant college culture — and therefore Honi coverage — has been met with furor for the last decade at the least.

Kate also pitched and published a cover story titled: “You want a Piece Of Me?” Honi comes to Britney’s defence” in 2008, at the height of the anti-Britney media circus. In comparison, a 2005 article compared iPods to girlfriends, with quips like, “I can switch it from Britney to Christina”. After widespread disdain for this casualised sexism, one activist ripped out the article from physical copies of the paper.

As for the university environment, she reflected that the SRC Women’s officer was viewed with a “lazy sort of animosity”, and hoped that current officers have it easier. Like Catriona and Rima, Kate felt “safer, louder, and more heard” in the Honi office than as a woman on campus, suggesting that the broader university environment was and still is “alarming.” She specifically referred to how sexual assault is addressed (or not) on campus, the protection of the Boys Club over accountability and the wilful lack of consent education. Kate concluded by acknowledging that multifold issues affect students of colour, LGBTQIA+ community, and those living with disabilities and mental health conditions, signalling a shift into the 2010s-20s where these concerns became more prominent in discourse.

Rolling into today: 2010-present

Honi’s coverage of women’s issues during these decades holds a mirror to key debates in society and university; over the course of 2010-2020, there is clear evolution in terms of Honi’s feminist priorities and approaches to the movement.

In the early 2010s, predominantly female writers for Honi opined on government paid maternity leave, abortion rights and equal pay; the coverage of women’s issues often embodied a ‘girlboss’ feminism undertone. Figures such as Tanya Pilbersek, Oprah and Tina Fey were lauded, and feminist criticism was often reserved for governmental policy. Laced throughout the editions is a palpable fear of an Abbott-led coalition and the resulting impacts on women’s rights. The question of affirmative action in USU elections was also a hot-button issue, with the publication of multiple op-eds against it; these mostly lent on the paternalistic argument regarding women’s satisfaction with employment based on ‘merit’.

The 2010s continued with autonomous Women’s editions, which display embryonic rumblings of the Burn the Colleges campaign, sparked by the 2009 scandal where a St Paul’s “pro-rape” Facebook page unearthed. In its early days, this campaign did not as strongly centre on colleges as the site of rape culture, and looked to society more broadly — this evolved significantly over the course of the decade. In 2012, the first ever survey on women’s safety took place, and the gathering of data was majorly propelled by Honi.

The criticism for Women’s Honi was severe, in part for its pro-choice stance but also its existence as an autonomous paper. In the early 2010s, protests against autonomous spaces and feminist politics erupted and manifested in the creation of societies such as the Men’s Society and LifeChoice. On similar lines, Women’s Honi received backlash from male students undercutting its importance by claiming “men’s struggles” are underreported and warrant an unique “Men’s Honi”. Dismantling these societies became a key focus of campus feminist organising and Honi pages, a movement that was criticised by Honi editor Connie Ye in 2012 as it detracted from focus on other issues and platformed a nefarious few.

2013 brought one of Honi’s most memorable ‘scandals’, colloquially known as ‘Vagina Soit’, where 18 initially-unfettered vulvas were displayed on the front cover. This whipped up a mixed maelstrom of support and backlash, even within feminist circles. Women’s Honi that year included an op-ed by a student who rejected the feminist label, writing, “now is the time to cease this worship of bra burning, Greer-like antagonism and kicking up a stink over the fact of our endogenous genitalia.”

Rolling into the latter years of the 2010s, Honi’s feminist arenas of debate resemble today’s more closely, centering on sexual violence in the colleges, culturally intersectional feminist concerns and debates on sex work and carceral feminism. In 2015, the Women’s Collective briefly cleaved in two with the creation of a Women of Colour Collective, representing an appetite for intersectional feminism. The watershed 2017 Broderick report on sexual violence in the colleges is a salient point marking Honi’s unshakeable anti-colleges stance, and begins a pattern of editorial investigation into the private institutions. In recent years, Honi and student politics has also been more self-reflexive, with the publication of articles investigating misogyny embedded in the campus left.

In the mid-2010s, affirmative action was introduced to Honi tickets, mandating that 50% of elected editors are non-cis men. In years 2010 and 2011, this now constitutional requirement would not have been met; from 2012-2023, the 50% threshold was likely just met. However, in the later 2010s, anecdotal evidence suggests this requirement rarely felt like a point of concern during ticket formation. Maddy Ward’s 2020 article opining that autonomous editions should be abolished as the relevant identities are “sufficiently represented in both the editorial team and the reporter pool” conveys a strong feeling of women’s inclusion in team formation and dynamics.

Honi spoke to 2015 Honi editor Rebecca Wong on gender dynamics within the Honi team. She flagged that it is “such a small group, and therefore hard to analyse gender issues at that level”, and also interestingly that Honi undergoes a process of rigorous selection and vetting of potential team members, potentially better weeding out misogynistic characters. She drew comparisons between Honi’s supportive and inclusive environment compared to societies such as SUDS or Revues, where she personally felt there were higher levels of sexism.

Honi’s improving environment for women’s exclusivity was in part preserved by “having guarding systems in place”, Rebecca explained. Affirmative action often helped ensure equality in speaking time, and Rebecca’s team insisted the chair of each meeting rotated so it was never one person dominating the discussion. Rebecca could recall one incident where a discussion felt like it ran on gendered lines, and believes this imbalance arose because some female editors were absent.

This systematic amelioration of the working environment for women marks progress from previous decades; but, considering anecdotal reports of misogyny in Honi and Honi-adjacent spaces such as student politics and student theatre, we cannot turn our heads away from discussions about women’s inclusion and participation.

As always, print media encapsulates surrounding societal mores; the transformation of Honi’s approach to feminist politics testifies to the work of feminist organising and female trailblazers on- and off-campus. As overt issues of sexism are resolved, we would be foolish to be self-congratulatory and close the book on our investigations of misogyny in Honi and at Usyd. The sexism of the past does not wash us clean of our obligations now; in the wake of continued sexual violence at the Colleges, and feminist struggles in all four corners of the world, a commitment to feminist coverage is needed more than ever.